This case has been decided. See how it turned out!

Can states pick up an annual $28 billion in sales taxes from online-retailers?

It’s no secret that online retail is where it’s at. Even better, a 1992 Supreme Court ruling says that a business doesn’t necessarily have to pay sales taxes to fulfill orders in a state. Only if the business has a physical presence in the state.

States have been fighting back, and now South Dakota has a chance to overturn the precedent in the Supreme Court.

South Dakota passed a law directly in spite of the “physical presence” requirement. The South Dakota law requires all online retailers that ship to consumers in South Dakota to pay South Dakota sales tax. In passing this law, South Dakota said, in effect, the 1992 ruling needs to be ditched, so we are passing a law directly against it and we hope to litigate it up to the Supreme Court.

The Quill rule

The 1992 case is Quill v. North Dakota. North Dakota had tried to force Quill, a mail-order shop based outside of the state, to pay taxes for sales shipped into the state. The Supreme Court ruled that states cannot charge sales taxes to a “vendor whose only contacts with the taxing State are by mail or common carrier.”

Although the ruling was made in a different era, it would seem to apply to online retailers. But has the nature of the game changed so that the Supreme Court needs to reconsider the rule?

Constitutional roots

The Quill rule has Constitutional roots. It’s an interpretation of the Constitution’s Commerce Clause, which is concerned with the federal government’s ability to regulate the national economy without interference from the states. Because Quill is merely an interpretation of the Commerce Clause, the Supreme Court could uphold the Constitution and still throw out Quill’s physical presence requirement.

What are the Constitutional boundaries?

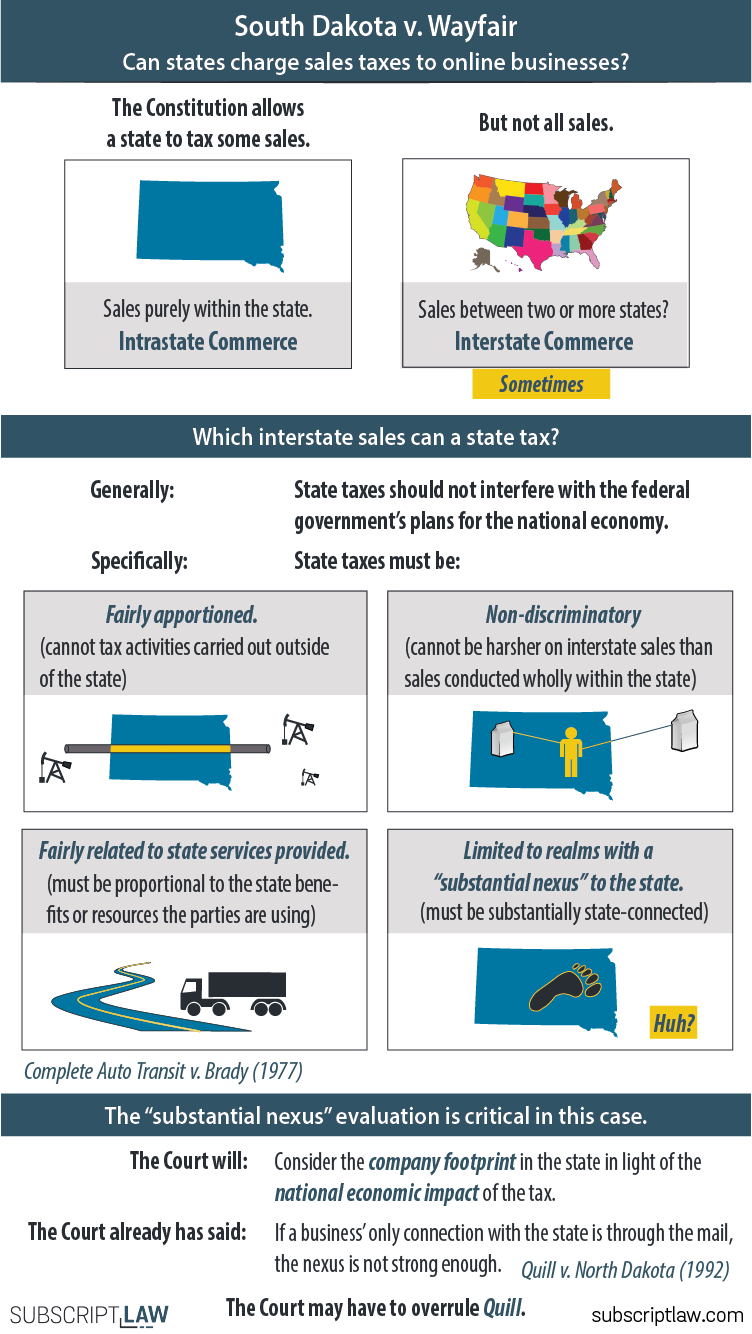

From the birds-eye view, the Commerce Clause limits states’ taxing of sales between two or more states. In other words, the Commerce Clause does not care about a regular sale that happens entirely within one state, but it’s triggered when a sale involves two or more states (“interstate”).

However, the Commerce Clause does not forbid taxes on any interstate sale. It only prohibits those taxes which would interfere with the federal government’s plans to regulate the national economy. That still sounds too abstract, and the Supreme Court has tried to narrow it down over time. In 1977, the Court came up with a four-factor analysis to determine whether the Commerce Clause is being violated by a state tax (Complete Auto Transit v. Brady). Those are the four factors that are listed in our infographic.

Substantial nexus

The fourth “substantial nexus” factor is where this case’s controversy lies.

Quill, which came 15 years after the Court established the 4-part test, decided to further narrow the substantial nexus factor. The substantial nexus factor – in all its cloudiness – has something to do with a company’s footprint in the state. A state cannot tax a company that is not substantially connected to the state in a certain way.

Quill decided that having a substantial connection with a state at least must include having a physical presence there. The Court thought the clarity of the physical presence requirement outweighed its potential arbitrariness. The Court admitted that the rule “appears artificial at its edges” but said the artificiality “is more than offset by the benefits of a clear rule.”

The Court will decide whether to reformulate the substantial nexus requirement and ditch the physical presence requirement. Perhaps the Court will find a substantial economic connection with a state is more apt than a physical presence. Perhaps the Court will leave the physical presence requirement intact but choose to redefine it. For example, Massachusetts has declared that companies that place cookies on Massachusetts’ residents computers are physically present in the state.

Impact of the case

Will it affect my Amazon purchases? Actually, no. Amazon already has agreed to pay sales taxes in all of the states that charge it. After years of fighting states on the issue, it threw in the towel. Of course, that means the company passes the taxes on to customers.

Walmart and Target also comply with sales tax requirements for their online orders because they each have a “physical presence” in every state.

But what about the tons of other online retailers?

The companies that brought this case (Wayfair, Overstock and Newegg) do not have physical presences in every state. They and businesses like them generally only pay sales taxes in states in which they have a physical presence.

If the Court overrules Quill, or otherwise reformulates the substantial nexus requirement to include broader relationship between companies and states, consumers could pay slightly more for online purchases. And states will gain a significant amount of money to spend on general budget items like public schools, departments and programs.