Convicted of murder by 10 of 12 jurors – is that enough?

In the United States Supreme Court

| Argument | October 7, 2019 |

| Decision | April 20, 2020 |

| Petitioner Brief | Evangelisto Ramos |

| Respondent Brief | Louisiana |

| Court Below: |  Louisiana Fourth Circuit Court of Appeal |

Case Decision

On April 20, 2020, the Supreme Court issued a decision in favor of Ramos.

Scroll down for our Decision Analysis.

August 14, 2019

Evangelisto Ramos was convicted of murder by a 12 member jury, and only 10 of them believed he did it. Under federal law, a non-unanimous verdict wouldn’t cut it. The Constitution doesn’t allow it. But the Supreme Court has ruled that states can convict with less.

The Constitution

The Sixth Amendment of the Constitution provides protections in criminal proceedings:

-

The right to a speedy and public trial

-

The right to an impartial jury

-

The right to be informed of the nature and cause of the accusation

-

The right to be confronted with the witnesses against him

-

The right to have compulsory process for obtaining witnesses in his favor, and

-

The right to have the Assistance of Counsel for his defence.

It does not specifically mention that juries must be unanimous, but long ago the Supreme Court decided that the Sixth Amendment does include the requirement. In 1898, the Supreme Court said that the Constitution’s Framers intended juries to have 12 members and that a guilty verdict must be unanimous:

[T]he wise men who framed the Constitution of the United States and the people who approved it were of opinion that life and liberty, when involved in criminal prosecutions, would not be adequately secured except through the unanimous verdict of twelve jurors.

The Fourteenth Amendment’s “incorporation doctrine”

The Thompson v. Utah decision was taken to apply to federal criminal trials because the Constitution originally applied only to the federal government. States were supposed to be separate “sovereigns,” and they could do their own thing.

The end of the Civil War changed the relationship between the federal and state governments. The Reconstruction Amendments put restrictions on states that hadn’t been contemplated before. Among them was the Fourteenth Amendment, stating that “[No state shall] deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law.”

In the years following the 14th Amendment, the Supreme Court has used this “due process clause” to apply a number of the protections of the Bill of Rights to state governments. Not all of them. But many of them. And it’s been less-than-clear which ones get “incorporated.” That’s the “incorporation doctrine.”

This case is about whether the Sixth Amendment’s unanimity requirement should be incorporated to apply against state governments.

Sixth Amendment incorporation

Let’s start with the general right to get a trial by jury. That one is incorporated. The Supreme Court said so in Duncan v. Louisiana (1968). States must give juries in criminal trials. But what about unanimity of the verdict and the 12-member jury requirement?

Unanimity’s partner right, the 12-member jury requirement that was mentioned in the same breath in Thompson v. Utah failed to get incorporated against states. In 1970, the Supreme Court was asked to determine if a state could convict someone of a criminal charge with only a six-member jury (Williams v. Florida). The Supreme Court majority in that case ruled that states could have fewer than 12 members. Thus, even though states must have jury trials, those could be juries of six members.

Within two years, the Supreme Court was asked if the jury unanimity requirement applies to states. And the Court said no (Apodaca v. Oregon, 1972). But it was an “unusual” split decision. Four members of the Court said unanimity should be incorporated; another four said unanimity shouldn’t even apply in federal cases; and the remaining Justice said unanimity should apply in federal cases but not in state cases. That was Justice Powell, and his one vote made the ruling — although it should be noted that none of the other justices followed his logic.

Question in the case

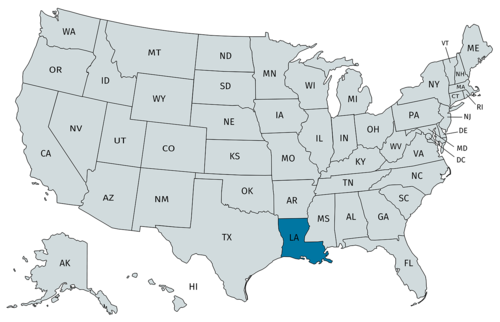

Getting back to this case, Ramos was convicted of murder by the State of Louisiana. Louisiana law requires only 10 of 12 jurors for a guilty verdict, and that’s the number that voted Ramos guilty. Ramos asks the Court to reconsider its decision on “incorporation” of unanimity. The Sixth Amendment requires unanimous verdicts in federal criminal cases, so it must require unanimous verdicts in state criminal cases.

Ramos’ view

Ramos’ brief to the Court outlines the history of the non-unanimous jury rule in Louisiana and of the rule in the only other state that has a non-unanimous jury rule: Oregon. According to the brief, unanimity on a jury is the only way to ensure fairness because defendants of minority races may only find one or two people on a jury who aren’t unfairly judging them. In Louisiana, the 9-of-12 jury rule (predecessor of the 10-of-12 rule) came as a result of a Constitutional convention with the purpose of ““assuring white political supremacy.” The 1898 Louisisana Constitutional Amendment imposed the 9-of-12 jury rule along with other racially discriminatory rules, like a poll tax and literacy tests for voting.

When Oregan made its 10-of-12 rule, the brief recounts, “Oregon was roiled by growing nativism and bigotry, including the rise of the Ku Klux Klan” and the Oregon Legislature acted in response to outrage over a Jewish man’s exculpation from a murder charge because of one jury member outlier to an otherwise unanimous conviction.

According to Ramos, jury unanimity in criminal cases is the only way to ensure the fairness that the Sixth Amendment requires. The Supreme Court already said that when it considered whether federal criminal cases must have unanimous verdicts, and there’s no reason the same justification isn’t true for state trials.

Incorporation in full

What might be the strongest argument for Ramos was foreshadowed last term in an opinion by Justice Ginsburg. Last term, the Court heard Timbs v. Indiana, a case in which a criminal defendant sought to have the Eighth Amendment’s excessive fines clause apply to state governments. The Court ruled, yes, the excessive fines clause applies to state governments.

Part of the Court’s ruling, written by Ginsburg, mentioned that once a right is incorporated to apply against states, it must be incorporated in full. The incorporation doctrine does not take watered-down versions of rights and apply them to states. But the one exception — Ginsburg mentioned in a footnote in Timbs — is the unanimity requirement of the Sixth Amendment.

The sole exception [to incorporating rights to state with the same standards as applied to the federal government] is our holding that the Sixth Amendment requires jury unanimity in federal, but not state, criminal proceedings. Apodaca v. Oregon, 406 U. S. 404 (1972). As we have explained, that “exception to th[e] general rule . . . was the result of an unusual divi-sion among the Justices,” and it “does not undermine the well-established rule that incorporated Bill of Rights protections apply identically to the States and the Federal Government.” McDonald, 561 U. S., at 766, n. 14.

The jury requirement of the Sixth Amendment is incorporated but the unanimity requirement is not. Does that “aberration” justify overturning Apodaca? Ramos says it does.

Louisiana’s view

Louisiana argued (in its opposition to certiorari) there’s no reason to overrule Apodaca. Most importantly, the right to a unanimous verdict isn’t actually in the Constitution. The Sixth Amendment says nothing about it. The right to a unanimous verdict is not fundamental to trial procedure, so it does not justify neglecting stare decisis (that courts should maintain precedent). Louisiana’s merits briefs may include additional arguments.

Changes in Louisiana too late for Ramos

Louisiana recently voted to end the 10-of-12 rule in favor of requiring unanimous verdicts in criminal cases. Unfortunately for Ramos, however, the new law will not apply retroactively to his case.

DECISION ANALYSIS:

On April 20, 2020, the Supreme Court issued a decision in Ramos v. Louisiana in favor of a man sentenced to life without parole, Evangelisto Ramos.

A Louisiana jury convicted Ramos of second degree murder with the assent of 10 jurors while 2 dissented. Ramos asked the Supreme Court to rule that a state criminal conviction must be unanimous. The Constitution’s Sixth Amendment already requires unanimous convictions in federal criminal trials, and Ramos asked the Court to rule that the requirement applies to states too.

The justices analyzed the strength of the Sixth Amendment right as well as the “incorporation” doctrine, which would apply that right to the states. Courts have commonly used the Fourteenth Amendment’s Due Process clause to apply a constitutional right to the states:

[No state shall] deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law.

Justice Gorsuch wrote the opinion of the Court, in which five justices agreed that the 14th Amendment “incorporates” the Sixth Amendment’s guarantee of jury unanimity in criminal trials. In other words, the guarantee applies to states. Breyer, Ginsburg, Sotomayor and Kavanaugh signed on to this portion of the ruling. The opinion became splintered (lost a majority of the Court) when it considered how to deal with the arguably precedential Supreme Court case, Apodaca v. Oregon (1972), which said that states need not have unanimous jury verdicts in criminal trials. In sum, however, all five members of the majority rejected reliance on Apodaca, ruling that the Constitution requires jury unanimity in state criminal trials.

Justice Thomas wrote a concurrence arguing that a different portion of the Fourteenth Amendment imposes the jury unanimity requirement on states (the Privileges and Immunities clause of the Fourteenth Amendment).

Justice Alito, joined by Chief Justice Roberts and Justice Kagan, filed a dissent saying that the Court should not have cast aside Apodaca, either by treating it as nonprecedential or by overruling it. The dissent would have left Apodaca’s ruling in place by giving respect to precedent (stare decisis).

Read the Supreme Court opinions here.