This case has been decided. See how it turned out!

CREDIT CARDS ACCEPTED WITH $10 MINIMUM PURCHASE.

It’s no secret that merchants pay credit card companies a fee. Merchants accept credit cards because paying with credit is easy on the consumer.

American Express makes a large portion of its money off of this fee. Visa and MasterCard – which profit mainly from consumer debt payments – charge lower merchant fees than Amex.

That’s why Amex builds self-protection into its contracts with merchants. If a merchant accepts American Express, it agrees that it will not steer consumers into using the other cards.

That’s why Amex builds self-protection into its contracts with merchants. If a merchant accepts American Express, it agrees that it will not steer consumers into using the other cards.

The Sherman Antitrust Act

Many years ago, the government decided that anti-competitive conduct is not good for consumers. Monopolies and other restraints on trade drive up consumer prices, and without regulation, the companies would take advantage.

The Sherman Antitrust Act was passed in 1890, banning contracts and conspiracies that restrain trade. The Supreme Court recognized the power of the Sherman Act (the federal government’s right to regulate monopolies) in 1911 when it ordered the break-up of the Rockefeller Standard Oil conglomerate.

The lawsuit against Amex by state attorneys general

Ohio and several other states argue the Sherman Antitrust Act bans the contract between Amex and the merchants because the contract is anti-competitive.

In this case, the attorneys general of several states sued Amex under the Sherman Act. Each state has an Office of Attorney General that serves to protect people in the state by bringing lawsuits on their behalf.

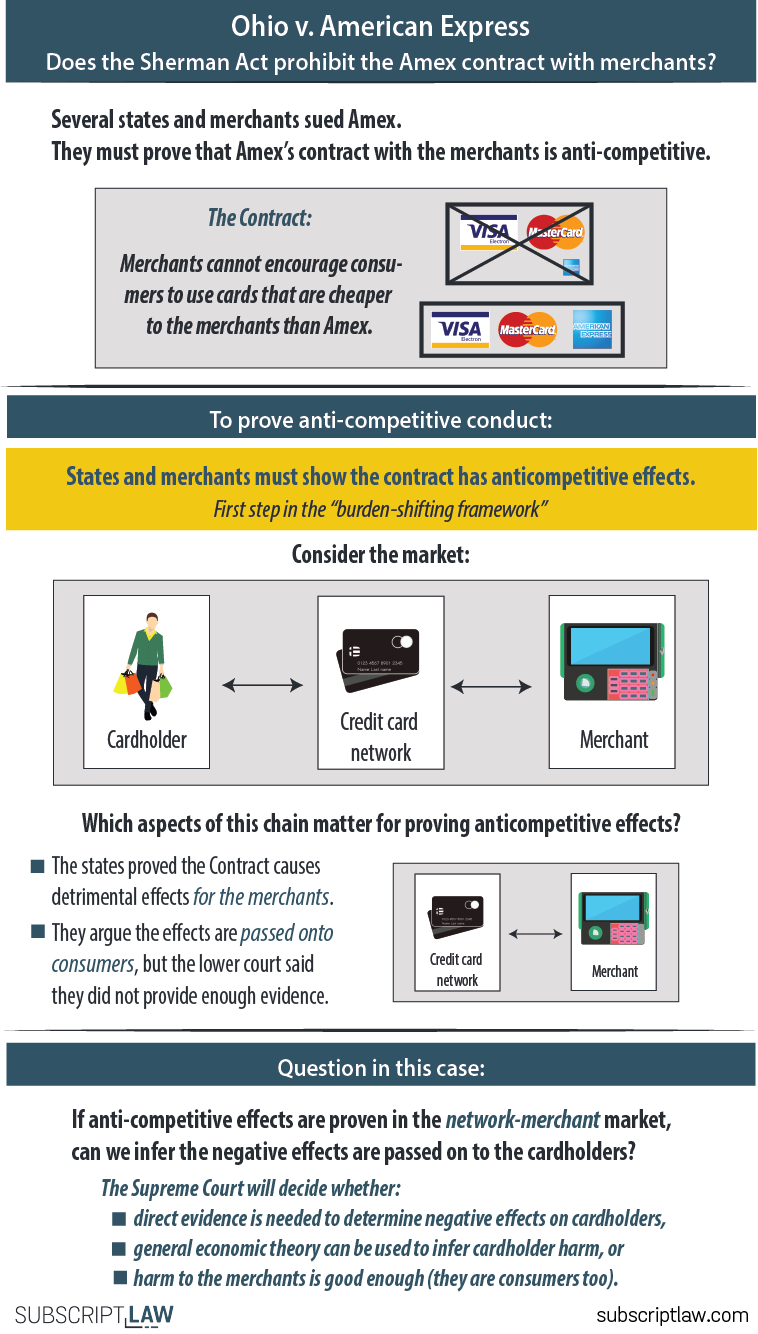

To prove a violation of the Sherman Act, the states must prove the contract produces anticompetitive effects in the market.

How do courts determine anticompetitive effects?

Economists have a hard enough time conducting market analyses, so you can imagine it’s no walk-in-the-park for a court. Of course, each side will produce expert evidence. And it’s the court’s job to sift through it.

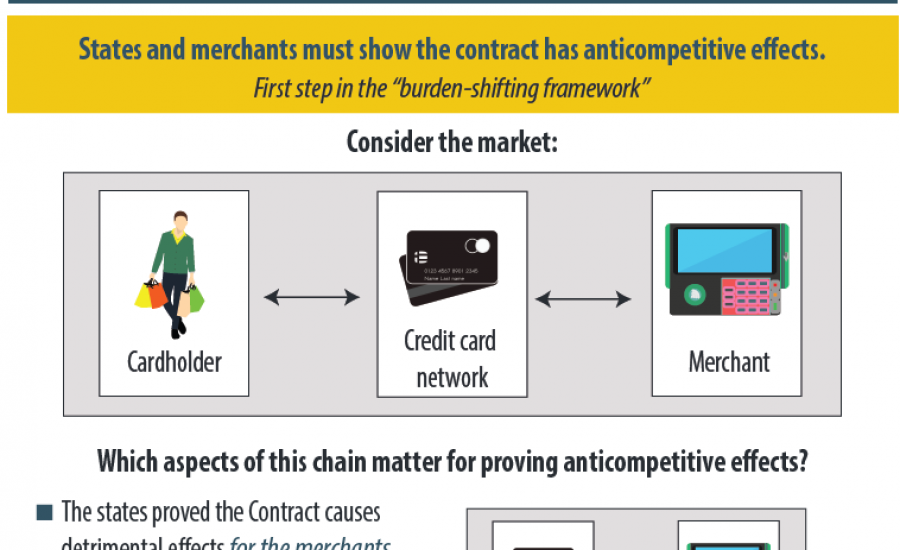

Burden-Shifting Framework

Courts sift through evidence using what is called a “burden-shifting framework.” A court will ask the plaintiff – the one who started the case – to produce some initial evidence supporting the plaintiff’s side. Then, if the plaintiff meets that burden, the burden shifts to the defendant, who will have an opportunity to rebut the inference made by the evidence.

This case is about whether the states met their initial burden.

Defining the market

In an antitrust case, the inferences that the evidence can support will often depend on how the court defines the market. A market that is too narrow or broad will lead to number-crunching lacking important numbers or including irrelevant ones.

The market definition is critical to this case. It is critical to determining whether the plaintiffs met their burden.

Two-sided market

As the infographic shows, credit card networks sit between the consumer and the merchants. Does the “market” include both sides of the market? Put another way, does the Sherman Act care if the merchants alone are hurt by the contract? Or alternatively, does the Sherman Act require the plaintiffs to determine that the harms are passed on to the cardholders?

The appeals court (Second Circuit) decided that the market (for antitrust analysis) must include the cardholders. The Sherman Act will not bar a contract that produces anticompetitive effects for the merchants only. The decision was fatal to the states’ case. The states had not provided enough evidence of negative effects on the cardholders.