Slow down, California. You can’t make women’s health clinics say that.

On Tuesday the Supreme Court ruled that certain notice requirements California imposed on women’s health clinics were likely to violate the First Amendment. The First Amendment case was brought by groups opposing abortion (identifying as “pro-life”).

Background

In 2015, the California legislature identified that millions of women were in need of publicly-funded pregnancy-related services (contraception, abortion, prenatal care and delivery). Further, although California had several state-sponsored healthcare programs that would help provide those services, many women were unaware the programs existed.

California determined that religious anti-abortion “crisis pregnancy centers” contributed to the women’s lack of information. California found these “CPCs” were giving less-than-complete information about 1) the nature of the services the centers provided and 2) the existence of state-sponsored medical services.

The FACT Act

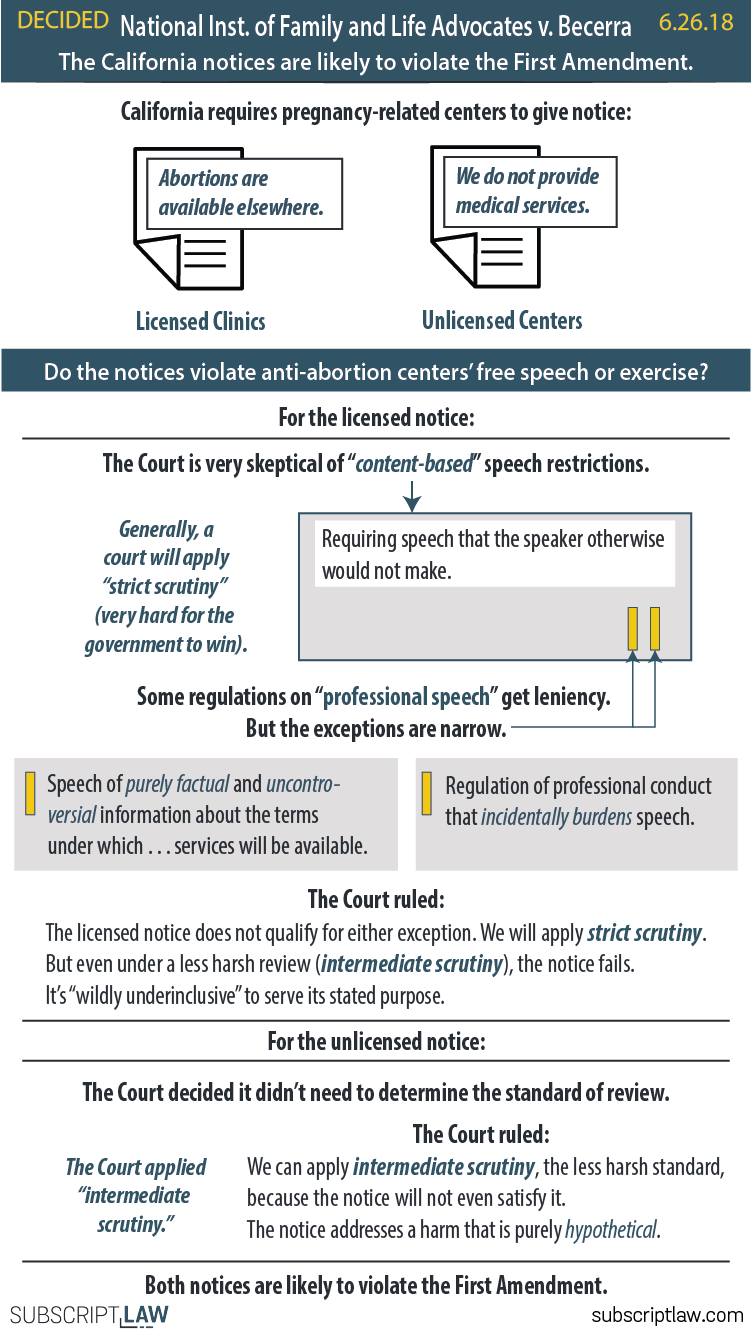

The state enacted the “FACT Act” to work towards better informing women. The FACT Act requires all California pregnancy-related medical centers to give their patients information about state-sponsored health options (including the availability of contraception and abortion services). And if a center is unlicensed to give medical services, the FACT Act requires it to disclose that it does not provide medical services.

The case

Feeling singled out, some anti-abortion pregnancy centers sued. The centers (NIFLA in this case), argued the California law discriminates against them based on their viewpoint. The First Amendment, they argued, prohibits the government from forcing people to speak the government’s message. And that is exactly what this law makes them do.

The First Amendment

The First Amendment protects people from government interference with free speech and free exercise of religion. Even with the First Amendment, however, some burdens on free speech are justified. The government has good reason to ban certain acts of speech. So the role of a court in a First Amendment case is to determine which laws go too far in burdening speech or religious exercise.

The level of scrutiny (or standard of review)

When a court evaluates whether a law violates the First Amendment, it considers the government’s purpose and whether the law is correctly designed to effectuate that purpose. But before it reviews the purpose and the design, the court must determine how skeptical it will be of the government. This process – determining a level of scrutiny – will guide the court in how harshly to scrutinize the law. The court is, in effect, determining the sensitivity of the issue with the importance of the type of regulation – before making an individualized decision on the exact regulation.

The Supreme Court’s determinations

The Court evaluated the notices separately. One of them could have qualified for some leniency from the court (less harsh level of review) because it’s a regulation on professional speech. That’s the notice regulating the licensed health clinics. However, the Court ruled both of the notices are not likely to pass First Amendment scrutiny.

For the licensed health notice, the Court noted that the exceptions for regulation of professional speech are very narrow. And this case would not qualify for either of them. But even so, the Court said, if we review the licensed notice under a less harsh standard of review (intermediate scrutiny), it will still fail. California said the purpose of the licensed notice was to “provide low-income women with information about state-sponsored service.” If that’s the case, the Court said, then California would have created a regulation that affected not just women’s health clinics but many other clinics too. The notice is “wildly underinclusive,” so it’s not “substantially related” to the government interest as intermediate scrutiny requires.

For the unlicensed notice, the Court assumed it could apply intermediate scrutiny because it said there was no need for a harsher level of review. California wouldn’t pass even intermediate scrutiny. The unlicensed notice, the Court said, addresses a harm that is “purely hypothetical.” According to the Court, California couldn’t even show that the regulation was made to address a real issue because the state did not say that women don’t actually know the difference between when they are receiving care from a licensed medical professional versus a clinic like this. Without knowing whether the problem really exists, California cannot make the regulation. Intermediate scrutiny requires the government interest be “important,” hence real.

What happens now?

In this case, the Supreme Court was deciding whether the 9th Circuit was correct in denying NIFLA a preliminary injunction. A preliminary injunction is a temporary remedy that a court may put in place while the full trial is ongoing, if the court believes the plaintiffs are likely to win. The 9th Circuit had ruled the plaintiffs (NIFLA) were not likely to win, and the Supreme Court turned that around.

So NIFLA will get its preliminary injunction. California’s notice requirements will be put on hold, while the case continues in court…as long as the state continues to fight it.