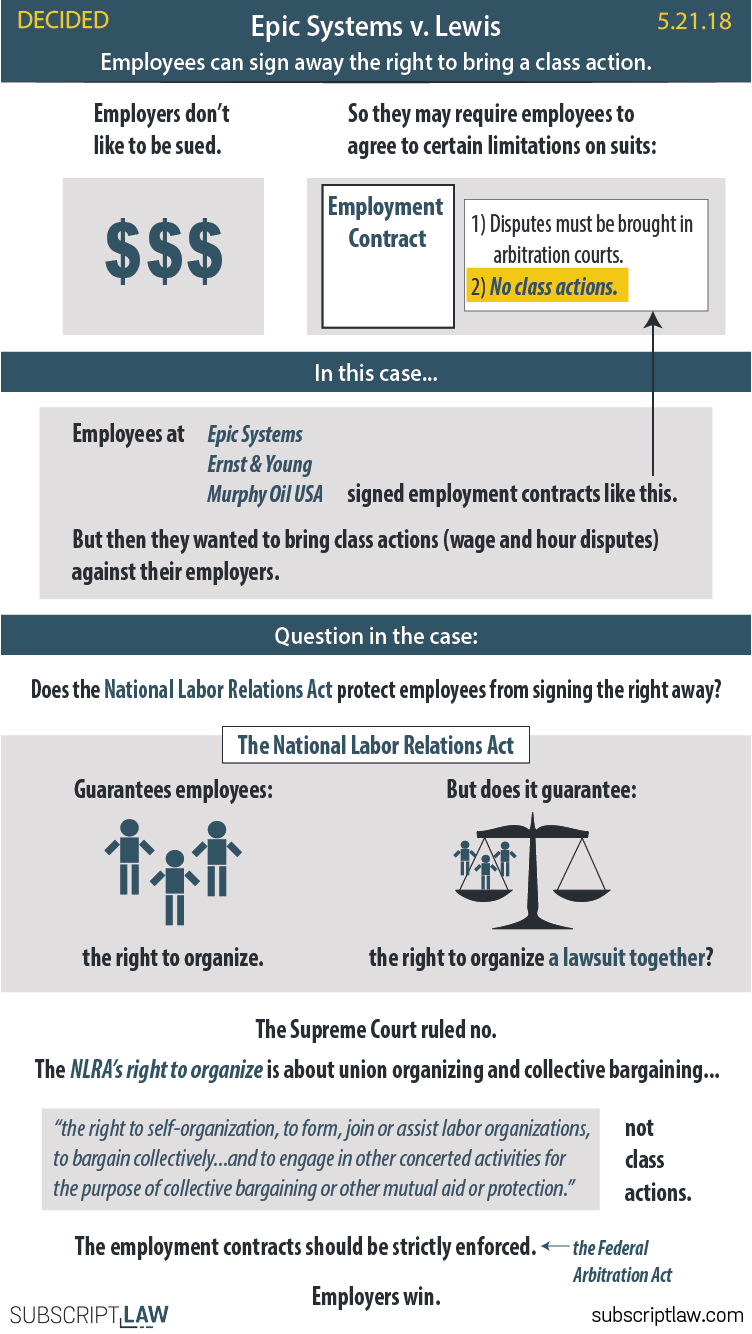

Employment contracts can require employees to sign away their rights to bring class actions.

The Supreme Court issued a major decision in favor of employers in Epic Systems v. Lewis. It was actually three consolidated cases. Employees at Epic Systems and two other companies (Ernst & Young and Murphy Oil USA) had signed similar language in their employment agreements. They agreed to bring their disputes in arbitration courts, and they agreed that they wouldn’t bring any class suits.

What the contract means

Agreeing to resolve all claims individually means that employees will have a much harder time bringing a lawsuit. If each employee has a dispute worth $2,000, for example, it may not be worth paying a lawyer to file the suit. On the other hand, if the employees can bring a class suit, each of their $2,000 claims combined could justify the cost of the litigation.

Basically, the provision is a cost-saver for the employers (keeping them practically immune from certain suits), while the employees usually end up having to accept their grievances.

Trying to get out of it

Most of us know that when you get offered a job, you have to just take it. Even if you’re in a position to bargain for a higher salary, you probably won’t waste your time worrying about the provision that keeps you from bringing a class litigation. After all, the company would just say it’s a mandatory part of the contract. So like the employees in this case, you’ll just sign.

These employees, however, realized later that they needed the right to bring class suits. They argued that there’s a federal law that protects them from having signed it away.

The National Labor Relations Act

In 1935, Congress recognized that employees needed protection against their employers because of the imbalance of power. The National Labor Relations Act guaranteed employees the right to organize in labor unions and to collectively bargain with their employers.

Here is the part of the NLRA that the employees argued supports their argument:

“[The Act guarantees] the right to self-organization, to form, join, or assist labor organizations, to bargain collectively . . . , and to engage in other concerted activities for the purpose of collective bargaining or other mutual aid or protection.”

They argued the “other concerted activities for the purpose of . . . other mutual aid or protection” covered class actions. Class actions, they argued, are activities for mutual protection, so the NLRA overrules the contracts they signed.

Not so.

The Supreme Court (in a 5-4 conservative-liberal split) ruled against the employees. The Court said that the NLRA is meant to guarantee collective activities like union organizing. A litigation is a completely different thing. Because it’s not in the same category as the other activities in the list, it cannot be included in the catch-all provision, as the employees argue.

There is another federal law, the Court noted, that covers this situation. It’s the Federal Arbitration Act. The FAA says that arbitration agreements must be strictly enforced. So following federal law requires us to conclude that the employment agreements are binding.

The dissent

Justice Ginsburg was heated. She read her dissent from the bench (a rare move). Supported by the other liberal-leaning justices, Ginsburg argued that the point of the NLRA was to reduce the power imbalance between the employees and employers. She interpreted the catch-all provision more broadly, saying “Suits to enforce workplace rights collectively fit comfortably under the umbrella ‘concerted activities for the purpose of . . . mutual aid or protection.

Ginsburg said the Federal Arbitration Act should not trump the NLRA’s demands. She said the FAA was enacted to help merchants of roughly equal bargaining power to be able to resolve their disputes efficiently. Nothing in the FAA says that it should apply to arbitration provisions in employment contracts.

No surprise

Despite the anger from the liberal wing, the decision comes as no surprise. The Supreme Court has been hostile towards consumer and employment class actions for years and has used the FAA consistently to side in favor of the party using the arbitration agreement.