“Census Case” heads back to the lower courts, but it’s unclear whether it will be resolved before the government must print the Census

In the United States Supreme Court

| Argument | April 23, 2019 |

| Decision | June 27, 2019 |

| Petitioner Brief | Department of Commerce |

| Respondent Briefs | New York et al. (Government Respondents) New York Immigration Coalition, et al. |

| Court Below |  US District Court, Southern District of New York |

On the last day of opinions for the 2018-2019 Term, the Supreme Court ruled on the highly anticipated “Census Case.” The Court did not outright reject the citizenship question, but it didn’t approve of it either.

Chief Justice Roberts plus the Court’s liberal wing didn’t buy the government’s justification for adding the citizenship question. The 5-member Court majority sent the case back down to the lower courts. They said the government must go back and better explain itself. It’s unclear, however, if that can happen before the Census questionnaire will need to be printed for 2020.

The case

In 2018, the Commerce Department announced plans to add a citizenship question to the Census. Citizenship isn’t a novel question for the Census. In the long history of the U.S. Census, the government has asked about either citizenship or birthplace or something to reveal immigration status the majority of the years. Since 2005, however, the government has had another means to get citizenship information and the question has dropped off of the survey.

When the question was set to reappear in the era of President Trump, however, some people became suspicious. The President has been accused of illegally targeting non-citizens in other policies, and a number of litigants challenged the citizenship question too. What was the government up to?

The government’s motivation

In this case, plaintiffs argued that the Commerce Secretary was using the citizenship question to dilute Democratic voting power. Knowing that the citizenship question would discourage people from answering the Census in Hispanic areas that tend to lean Democratic, the citizenship question would lead to an undercount in those areas, which would cause those areas less representation in Congress.

Secretary Ross said he has broad discretion to conduct the Census and courts should stay out of it. He had determined that asking about citizenship is necessary for the federal government’s interest in enforcing voter rights laws. Given that the citizenship question has appeared on the U.S. Census many times in the past, Ross defended, adding it now is nothing unusual.

The Supreme Court ruling

Several Justices wrote opinions on the case, and even the majority opinion written by Chief Justice Roberts was splintered (signed onto by other Justices only in part). Here’s the basic ruling and the precedential take-away.

The majority ruled that the Commerce Secretary Ross has broad power to administer the U.S. Census, and under ordinary standards of agency review, the Court will not overturn the Secretary’s decision to add the citizenship question. However, five Justices concluded, there is one exception to the general standard of agency review that requires the Court to send the case back. If a court finds a “strong showing of bad faith or improper behavior” on the part of the executive agent, then the court can look deeper at the agency decision-maker’s “mental processes.”

Based on the record as a whole in this case, a five-member majority (Roberts plus the liberal wing) determined that the government’s justification for adding the citizenship question was pretextual. The court reviewed the evidence regarding Secretary Ross’ decision-making process and found “a significant mismatch between the decision the Secretary made and the rationale [Ross] provided.”

The record shows that the Secretary began taking steps to reinstate a citizenship question about a week into his tenure, but it contains no hint that he was considering [voting rights] enforcement in connection with that project. The Secretary’s Director of Policy did not know why the Secretary wished to reinstate the question, but saw it as his task to “find the best rationale.”

Roberts’ opinion continued saying that the record shows that DOJ was only investigating the connection between citizenship information and voting rights enforcement upon a request by the Commerce Department, and not inherently for voting rights enforcement.

Thus, based on a review of the record, the Court ruled the voting rights justification was pretextual. The case will go back to the lower court for Secretary Ross to better explain the justification for adding the citizenship question.

The conservative wing was divided

Justice Roberts lost support of his conservative comrades in deciding the case should be sent back. Justice Thomas argued the Court improperly created a “pretext” rule that can invalidate agency action over and above the general APA standard. Alito wouldn’t have reviewed Secretary Ross’s actions at all (arguing federal law gave unreviewable discretion to the Secretary to conduct the Census).

The liberal wing

Justice Breyer wrote an opinion for the liberal wing. Although this group did agree that the case should be sent back because the Secretary’s justification for the citizenship question was pretextual, it would have rejected the Secretary’s actions under the general APA standard as well.

For more information on the arguments in the case, read our earlier analysis below.

Earlier Case Analysis

April 22, 2019

Can the government add the citizenship question to the U.S. Census?

The truth is, citizenship isn’t a novel question for the Census. In the long history of the U.S. Census, the government has asked about either citizenship or birthplace or something to reveal immigration status the majority of the years.

Since 2005, however, the government has had another means to get citizenship information and the question has dropped off of the survey.

Now, it’s back. And several lawsuits around the country are challenging the government’s motivation for bringing it back. This case is one of them.

The Trump Era

President Trump’s policies have raised questions of discrimination against immigrants from the start. So when the citizenship question was set to reappear in the 2020 Census, some people became suspicious of the government’s motivation.

Is it helpful to gather citizenship information, or will it cause more harm than good? And — the important question for this lawsuit — did the government violate law in adding it to the Census?

The lawsuit

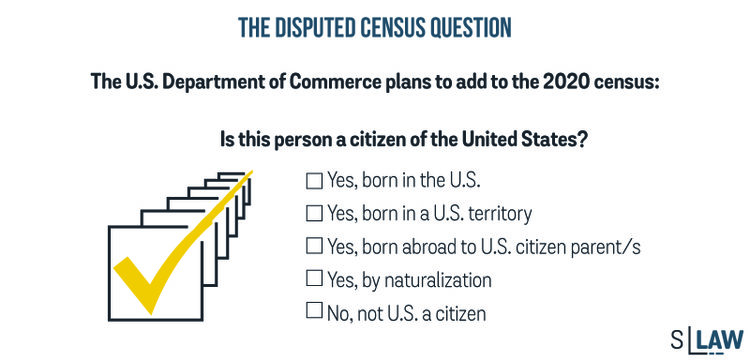

In 2018, the Commerce Department decided to update the Census to include a question asking if the respondent is a U.S. citizen. In justifying the change, Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross reported that the citizenship question is necessary for the federal government’s interest in enforcing voter rights laws. Given that the citizenship question has appeared on the U.S. Census many times in the past, Ross explained, adding it now is nothing unusual.

People sued. Lawsuits are alleging the government is trying to scare people out of answering the Census, which will lead to an undercount in areas with a large number of Hispanic people, which will lead to underrepresentation in Congress in those areas which tend to lean Democratic. The cases do not actually allege that the government will be using the Census to seek out illegal immigrants. In fact, that would be illegal. This case is more about the effects of an undercount and whether the government violated the law because it is using the Census for political reasons rather than for getting a population count.

The case currently before the Supreme Court came out of New York. A group of states, local governments and advocacy groups claimed that the Commerce Department violated the Constitution and federal laws.

Before getting into the legal claims, here is some background on the Census.

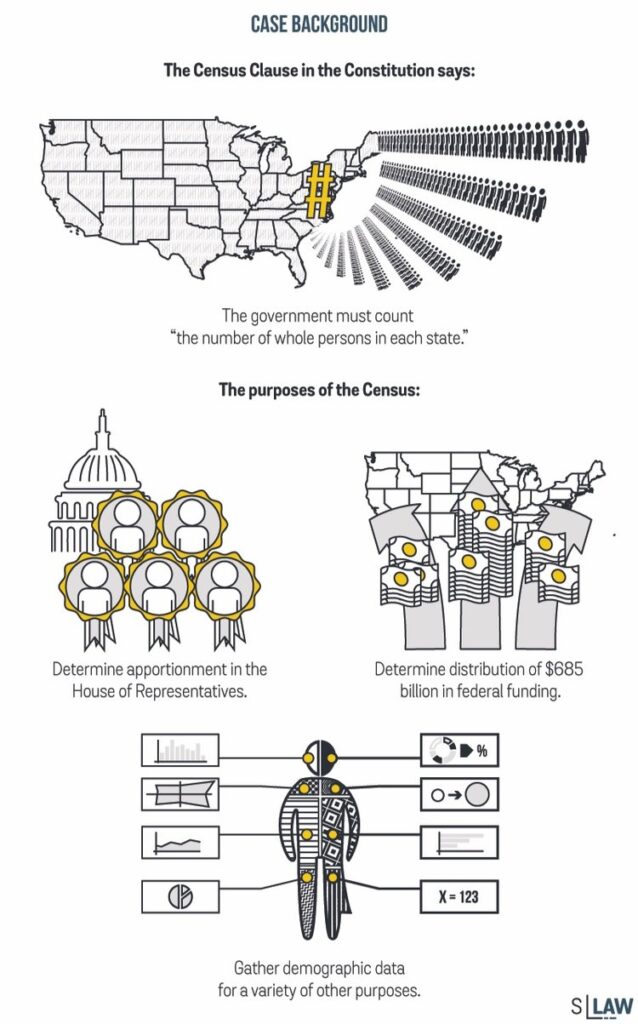

Background: The Census

The Constitution mandates a population count (the Census) every ten years for a few important purposes. For one — the primary goal of the Census — the count is used to determine apportionment in the House of Representatives. The government needs to know how many people live where, because House apportionment is based on population. The more people, the more representation.

Next, the Census population count helps the federal government distribute federal funding. The government distributes around $675 billion to localities. A region with more people gets more federal dollars.

And then there are a number of other reasons the government may want to have population or demographic data. The justification the Commerce Department named for adding the citizenship question falls into this category: to better enforce voting laws.

Plaintiffs’ claims

The plaintiffs are suspicious of this citizenship question, but it’s hard to pin down where the agency might be going wrong legally.

Here, again, is the basic argument: The government wants to scare people from answering the Census so that there will be an undercount in areas with more Hispanic people, leading to less political representation in those areas. And the government is motivated to do so because those areas tend to lean Democratic. It sounds possible, but it’s important to place the Commerce Department’s actions into (or outside of) its legal boundaries. Because suspicion doesn’t hold in court without legal violations.

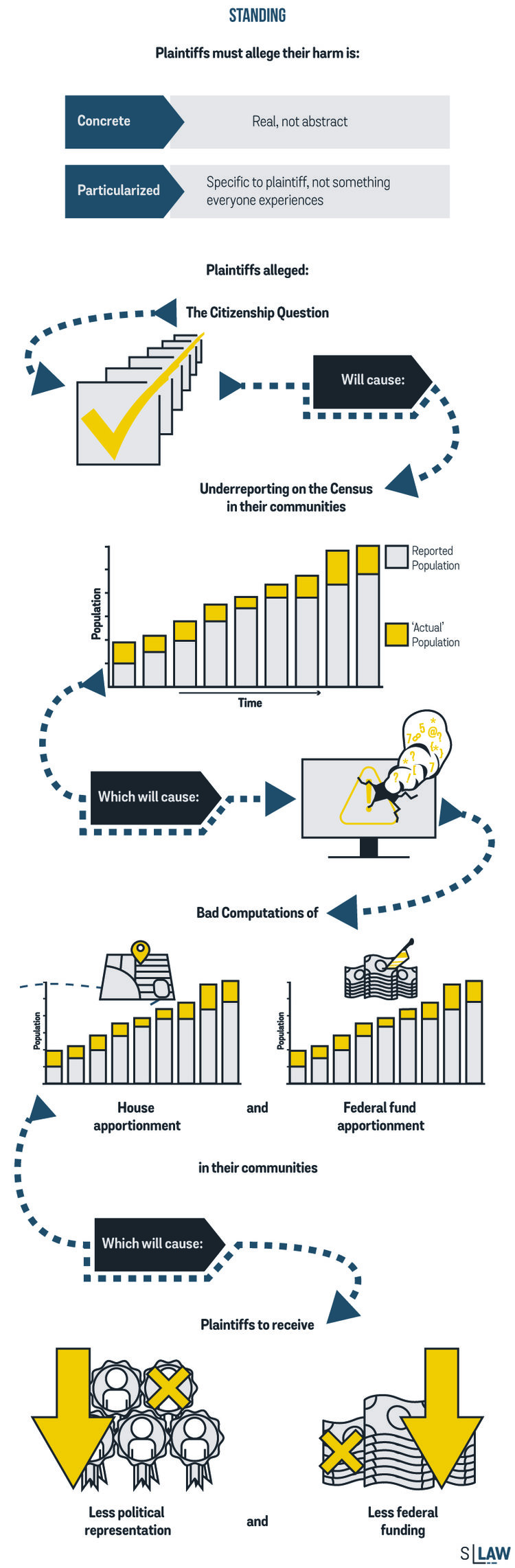

A preliminary question: standing

Before a plaintiff can get out of the starting gate, the plaintiff must show she has a particular stake in the issue. The plaintiff must show she will experience harm, and not just a general type of harm that everyone can experience (like a taxpayer may be harmed by a waste of federal dollars, United States v. Richardson (1974)), but a “concrete and particularized” harm. Why does the litigant have a particular stake in the case? That’s called standing, and the parties have been arguing about whether the plaintiffs have satisfied the standards here.

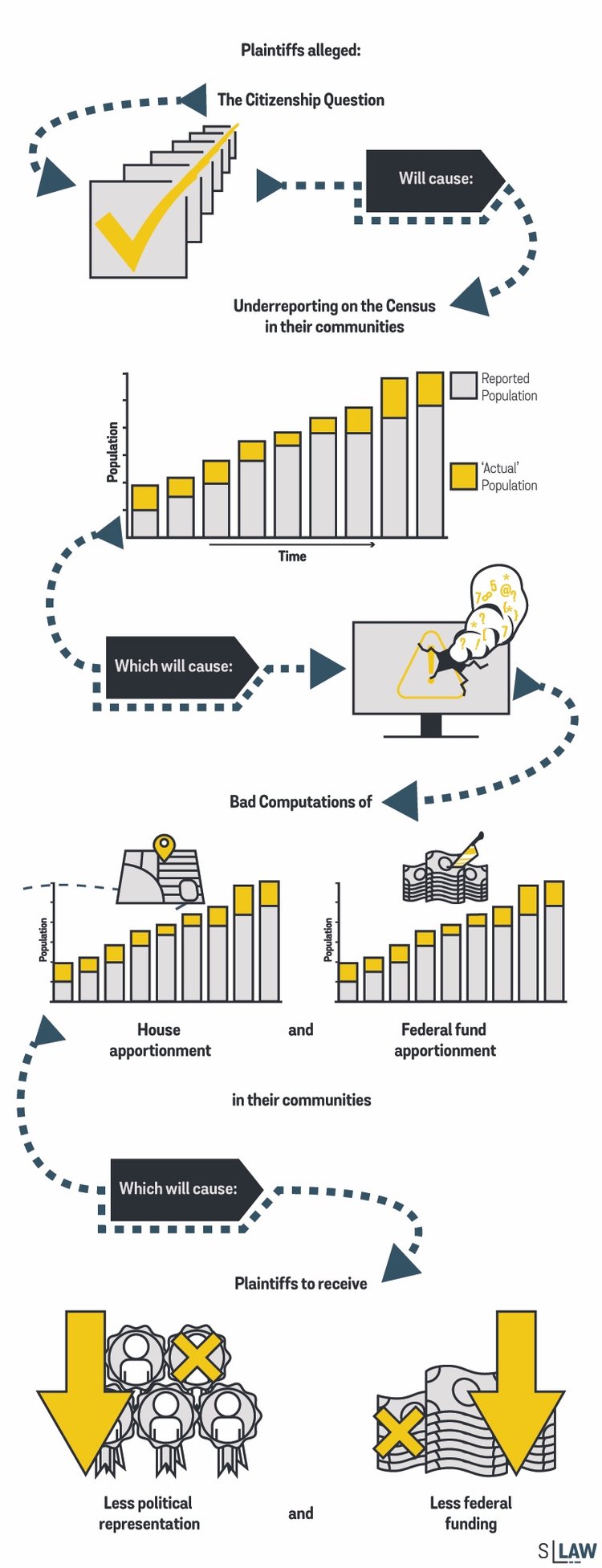

Plaintiffs argue: The citizenship question will cause underreporting on the Census in their localities; as a result, the federal government will think there are fewer people in their localities; as a result, plaintiffs’ localities will get less political representation and fewer federal dollars.

The Commerce Department fights back on the standing issue. In order for Plaintiffs to actually experience harm, Census respondents will have to violate the law (by not responding to the Census) based on a fear that the government is seeking (illegally) to use Census citizenship data to pursue people who are in the country illegally. The Commerce Department argues this is too much of a stretch, and standing shouldn’t be based on such projections of how people may act (illegally, no less).

The federal courts in New York granted the plaintiffs standing. If the Supreme Court overturns the ruling on plaintiffs’ standing, it may not get to the substantive questions of law. Assuming standing is valid, here’s the heart of the case.

Did the Commerce Department violate the law?

The plaintiffs claimed that the Commerce Department violated the Constitution (the Census clause) and federal laws.

The Constitution: The “Enumeration Clause” of the Constitution is the part that mandates Congress to count people. Congress then gave that power to the Commerce Department. Plaintiffs claim the Commerce Department’s adding the citizenship question violates the clause because the citizenship question will result in a bad population count. Moreover, localities with a large number of Hispanic people will miss out more than others, which means (presumably) the government was aiming to dilute the political power of Democratic communities. The government cannot use the Census for its own political reasons, rather than for getting a good population count.

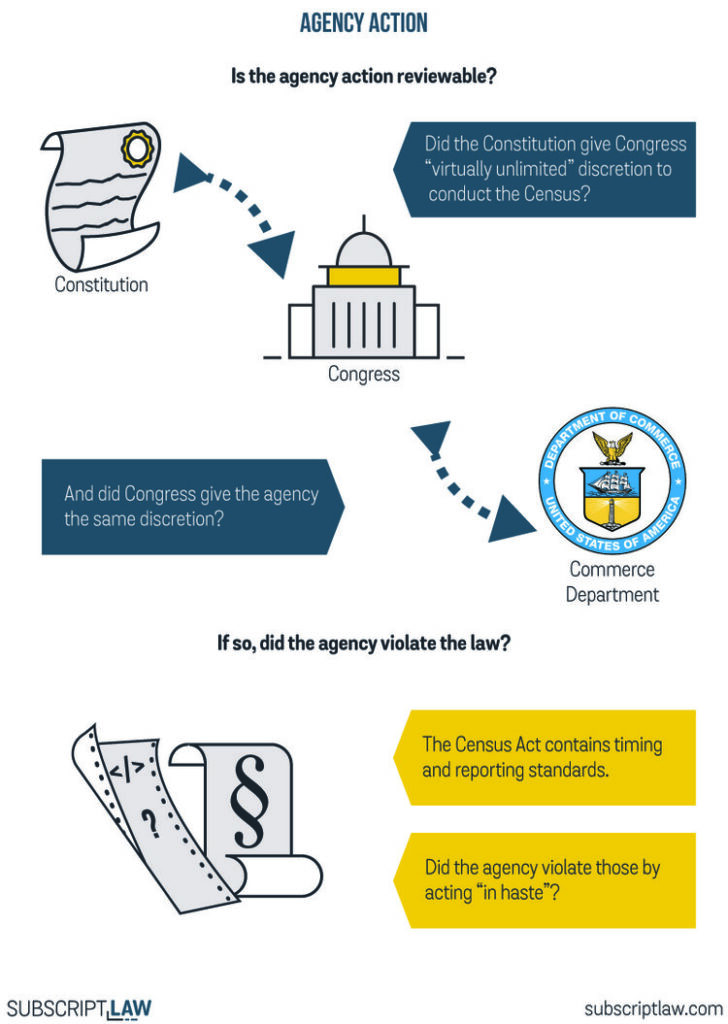

Federal laws: In response to its Constitutional mandate to count people (the Enumeration Clause), Congress enacted the Census Act. The Census Act tells the Commerce Department to do XYZ, and then the Commerce Department gets to act within those boundaries to conduct the questionnaire. And voila, a Census count.

The Plaintiffs believe the Census Act places strict restrictions on the Commerce Department, and the Commerce Department believes it has “virtually unlimited” discretion to conduct the Census count.

Plaintiffs argue the Census Act incorporates the strict requirement that the Commerce Department do its best to make an “accurate” count. Of course, no one thinks the Department can create an exact population count, but can the Commerce Department make a decision that it knows will cause underreporting (like adding the citizenship question)? The government says it can, as long as it has determined the benefits of the decision outweigh the risks. And — the government says — courts must trust that the agency has made the proper analysis (don’t second-guess agency decision-making).

Next, the Plaintiffs mention a provision of the Census Act that says the Commerce Department must use administrative records (elsewhere) to obtain demographic information, “to the maximum extent possible,” instead of conducting direct inquiries on the Census. Plaintiffs argue that Congress included that provision because it recognized that having too many questions on the Census in the past has deterred people from responding (causing underreporting). Plaintiffs argue this is a strict requirement, and the government argues the requirement doesn’t give any real standards (“to the maximum extent possible”), so courts really just must trust the agency.

The lower court determined the Commerce Department did, in fact, violate the Census Act. Now, the Commerce Department argues to the Supreme Court that these limitations aren’t the type of provisions that courts are supposed to be picky about, or even be reviewing. The Census Act, in the Commerce Department’s view, gives the agency “virtually unlimited” discretion to conduct the Census. Courts generally shouldn’t nit-pick agencies’ decisions when it comes to areas within their discretion, so the courts really shouldn’t be getting involved with these provisions that lack real standards for review.

The Supreme Court will decide whether to respect the Commerce Department’s discretion over and above the provisions the plaintiffs point out, or at least if it will give the Commerce Department the benefit of the doubt when it comes to interpreting the provisions.

Plaintiffs also call on the Administrative Procedure Act (APA) to try to show the Commerce Department’s wrongs. The APA gives general guidelines on agency behavior. Agencies must follow the law (that’s already obvious), but when the law gives agencies discretion on how to act, the APA outlines the standards agencies must meet in order to act appropriately within that discretion. For example, when an agency issues rules, it must follow certain reporting and public notification standards. More generally, an agency can’t act in an “arbitrary or capricious” manner, or abuse its discretion.

The Supreme Court will determine whether the agency violated the Census Act, and it will also see if the agency generally abused its discretion or failed to follow proper procedures. The plaintiffs argue the Department abused its discretion, for example, by ignoring evidence about the effects of adding the citizenship question and creating a pre-textual justification for adding the citizenship question.

The Supreme Court will hear arguments on April 23, 2019.