Facts of the Case from Oyez:

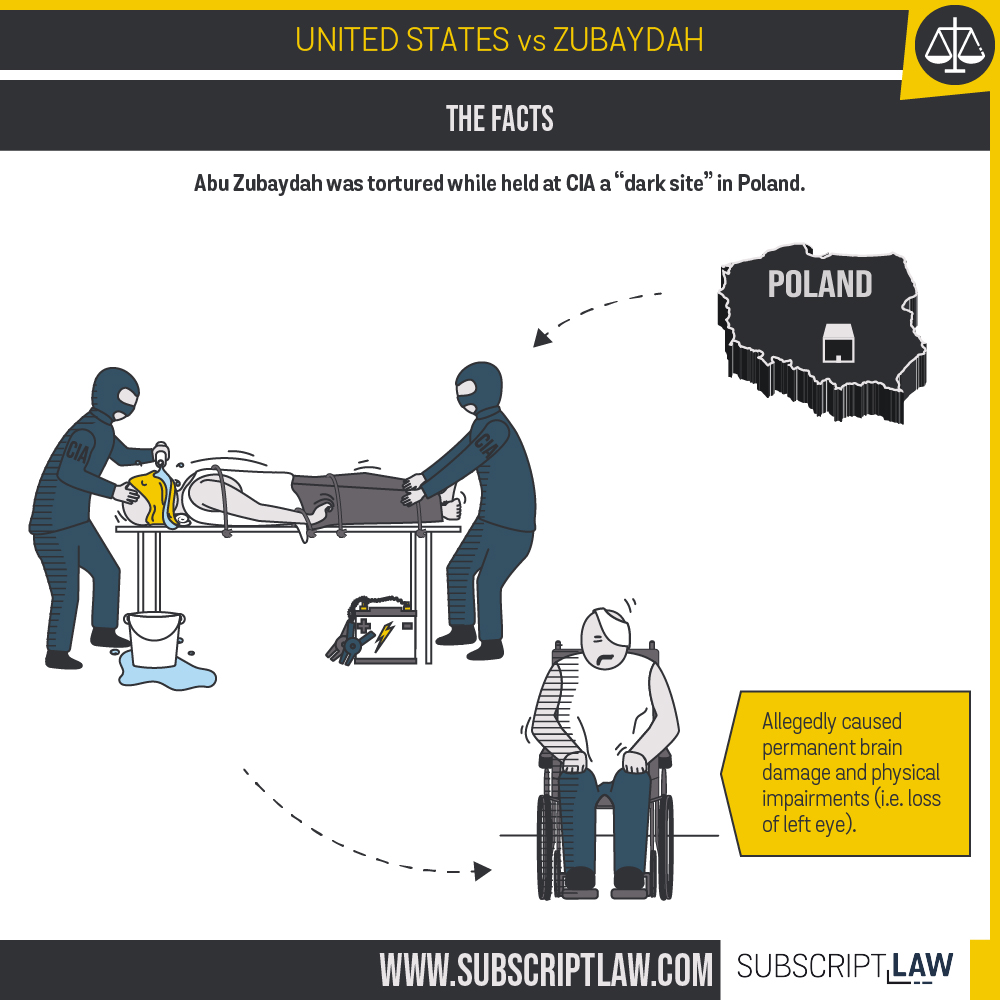

Zayn Husayn, also known as Abu Zubaydah, is a former associate of Osama bin Laden. U.S. military forces captured him in Pakistan and detained him abroad before moving him to the detention facility at Guantanamo Bay, where he is currently being held. Zubaydah alleged that, before being transferred to Guantanamo, he was held at a CIA “dark site” in Poland, where two former CIA contractors used “enhanced interrogation techniques” against him. Zubaydah intervened in a Polish criminal investigation into the CIA’s conduct in that country, and he sought to compel the U.S. government to disclose evidence connected with that investigation.

The government has declassified some information about Zubaydah’s treatment in CIA custody, but it has asserted the state-secrets privilege to protect other information. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit rejected the government’s assertion of state-secrets privilege based on its own assessment of potential harms to national security and allowed discovery in the case to proceed.

Visit Oyez.

Question in the Case from Oyez:

Did the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit err in rejecting the federal government’s assertion of the state-secrets privilege based on its own assessment of the potential harms to national security that would result from disclosure of information pertaining to clandestine CIA activities?

Visit Oyez.

Ninth Circuit Decision

PAEZ, Circuit Judge

:

Zayn al-Abidin Muhammad Husayn (“Abu Zubaydah”) is currently held at the U.S. detention facility in the Guantanamo Bay Naval Base in Cuba. Abu Zubaydah was formerly detained as part of the Central Intelligence Agency (“CIA”)’s detention and interrogation program, also commonly known as the post-9/11 “enhanced interrogation” or torture program. In 2017, Abu Zubaydah and his attorney, Joseph Margulies (collectively “Petitioners”), filed an ex parte application for discovery pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 1782, which permits certain domestic discovery for use in foreign proceedings. They sought an order to subpoena James Elmer Mitchell and John Jessen for their depositions for use in an ongoing criminal investigation in Poland about the torture to which Abu Zubaydah was subjected in that country. The district court originally granted the discovery application, but subsequently quashed the subpoenas after the U.S. government intervened and asserted the state secrets privilege.

Abu Zubaydah’s birth name was Zayn al-Abidin Muhammad Husayn but he is known as Abu Zubaydah in litigation and public records.

The Supreme Court has long recognized that in exceptional circumstances, courts must act in the interest of the country’s national security to prevent the disclosure of state secrets by excluding privileged evidence from the case and, in some instances, dismissing the case entirely. See Totten v. United States , 92 U.S. 105, 23 L.Ed. 605 (1875) ; see also United States v. Reynolds , 345 U.S. 1, 73 S.Ct. 528, 97 L.Ed. 727 (1953). This appeal presents a narrow but important question: whether the district court erred in quashing the subpoenas after concluding that not all the discovery sought was subject to the state secrets privilege.

We have jurisdiction pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 1291, and we reverse. We agree with the district court that certain information requested is not privileged because it is not a state secret that would pose an exceptionally grave risk to national security. We also agree that the government’s assertion of the state secrets privilege is valid over much of the information requested. We conclude, however, that the district court erred in quashing the subpoenas in toto rather than attempting to disentangle nonprivileged from privileged information.

We have “emphasize[d] that it should be a rare case when the state secrets doctrine leads to dismissal at the outset of a case.” Mohamed v. Jeppesen Dataplan, Inc. , 614 F.3d 1070, 1092 (2010) (en banc); see also Reynolds , 345 U.S. at 9–10, 73 S.Ct. 528 (noting that “[j]udicial control over the evidence in a case cannot be abdicated to the caprice of executive officers”). Here, the underlying proceeding is a limited discovery request that can be managed by the district court, which is obligated “to use its fact-finding and other tools to full advantage before it concludes that the rare step of dismissal is justified.” Mohamed , 614 F.3d at 1093. We therefore reverse the district court’s judgment dismissing Petitioners’ section 1782 application for discovery and remand for further proceedings.

Read the full opinion on CaseText.

Summary of Argument (Brief of Petitioner, the United States)

In this proceeding to obtain classified information from former CIA contractors for use in a foreign proceeding investigating alleged CIA activities abroad, a divided panel of the Ninth Circuit erroneously held that discovery could proceed under Section 1782. The panel’s decision poses significant national-security risks and is seriously flawed on two independent grounds.

A. First, Section 1782 does not extend to information protected by “any legally applicable privilege,” 28 U.S.C. 1782(a), and, here, the state-secrets privilege protects information that would confirm or deny whether or not a CIA detention facility was located in Poland with any relevant assistance from Polish authorities. The former CIA Director explained why the compelled discovery of such information from Mitchell and Jessen would risk the national security. The CIA informs this Office that the current CIA Director has likewise determined that the compelled discovery of that information would reasonably be expected to harm the national security and that the government should therefore continue to oppose discovery of that classified information in this case.

1. The Ninth Circuit fundamentally erred in rejecting the government’s privilege assertion. The panel majority’s errors primarily derive from its failure to afford appropriate deference to the CIA Director’s judgment regarding risks of harm to the national security. Courts properly extend “the utmost deference” to Executive Branch assessments of such harms, Department of the Navy v. Egan, 484 U.S. 518, 529-530 (1988) (citation omitted), reflecting the Executive’s central constitutional role in this context. The majority, however, erroneously determined that its “essential obligation” was to conduct a “skeptical” review, which it recognized “contradict[ed]” prior circuit precedent acknowledging the need for deference. Pet. App. 14a-15a, 17a n.14. The majority’s standard, and its consequent disregard of the CIA Director’s detailed declaration, is a serious departure from established principles which alone warrants reversal of its judgment.

2. The majority further erred in the course of making its own independent assessment of national-security harms. The majority believed that no harm would result from the compelled discovery of information about alleged clandestine intelligence activity from former CIA contractors because such contractors are “private parties.” Pet. App. 18a. That is clearly incorrect. The state-secrets privilege has long protected national- security information possessed by government contractors. The rule could not be otherwise.

3. a. The majority’s willingness to reject the Executive Branch’s national-security judgment based on its own assessment of purported “public knowledge” likewise fundamentally misapprehends the governing principles. Courts have long recognized that the existence of widespread public speculation without official government disclosure provides no sound basis to require government personnel to confirm or deny the accuracy of the speculation. That principle applies with particular force in the world of clandestine intelligence operations.

b. The majority’s independent analysis of “public knowledge” based on an ECHR judgment and news stories underscores its methodological error. The ECHR had no direct information about any purported CIA activities in Poland; it based its judgment against Poland on adverse inferences it drew because Poland refused to confirm or deny Abu Zubaydah’s allegations. The news stories, in turn, rested on prior stories and hearsay, often from unnamed sources. And reporting about statements attributed to Poland’s former president, who reportedly had repeatedly denied the existence of any CIA detention facilities in Poland, at best demonstrates conflicting statements, not a basis for “public knowledge” that could override the CIA Director’s considered judgment on matters of national security.

4. The panel’s errors are particularly significant because respondents seek discovery for use in a foreign proceeding that is investigating alleged clandestine activities of the CIA abroad. That context warrants a particularly high degree of deference to the CIA Director’s assessment. The Director’s detailed declaration therefore far exceeds the requisite showing to sustain the government’s privilege assertion.

Read the full brief.

Summary of Argument (Brief of Respondent, Zubaydah)

The state secrets privilege, as applicable here, is an evidentiary rule that excludes privileged evidence from discovery. It does not exclude nonprivileged evidence. As such, Reynolds and its progeny have carefully defined the contours of the privilege to ensure there is no greater infringement on the interests of justice than national security demands. This requires courts to scrutinize the Government’s privilege assertions and to permit discovery of nonprivileged information. In conducting this analysis, courts properly defer to the Executive’s assessment that the disclosure of secret information will harm national security. But there is no special executive branch knowledge, and therefore no reason for deference, on the factual question of whether information is secret; or on the judicial question of how the matter should proceed when a discovery request seeks both privileged and nonprivileged information.

The court of appeals correctly applied these principles. It critically examined the Government’s privilege claim and upheld most of it, deferring to the judgment of former-CIA Director Pompeo on the question of whether disclosure of actual secrets—like the identities of Polish nationals—would harm national security. But the court recognized that a subset of information was not privileged, including Abu Zubaydah’s conditions of confinement and the details of his interrogation, as well as the publicly known, repeatedly confirmed historical fact that a CIA black site existed in Poland. And although the Government argues that “official confirmation” of this historical fact would work unique harms, the court of appeals properly held that “official confirmation” is not at issue here, because the witnesses are not agents of the Government and cannot speak on its behalf. Under settled law, the court of appeals was correct to reverse and remand to the district court for further proceedings.

The Government incorrectly portrays that decision as a failure of deference. Yet the Government offers no workable principle to limit the degree of deference it demands. To the contrary, the Government’s argument would produce absolute deference, which would impermissibly transfer judicial control over the evidence in particular cases from Article III judges to Article II officers. This Court has consistently warned of the dangers inherent in such an approach. The Court should affirm the court of appeals and leave in place a rule that has served the Nation for nearly seventy years.

The Government’s alternative argument—that the district court “would have” abused its discretion under §1782 by permitting discovery to proceed—was neither presented nor fairly included in the Petition and should be rejected for that reason alone. It also mischaracterizes the procedural posture by ignoring that the district court undertook a §1782 discretionary analysis only when granting the discovery Application, not when quashing the subpoenas. In its order granting the Application, the district court assessed the discretionary factors under Intel and found they weighed in favor of discovery, rejecting the Government’s contrary arguments. The Government now ignores all of this, effectively asking this Court to review de novo whether discovery was properly granted under §1782, without reference to the actual arguments presented to the district court and the court’s treatment of those arguments.

Read the full brief.