- Subscript Law Exclusive Report

- Facts

- Case Question

- Decision Below

- Petitioner’s Argument

- Respondent’s Argument

Factual Background

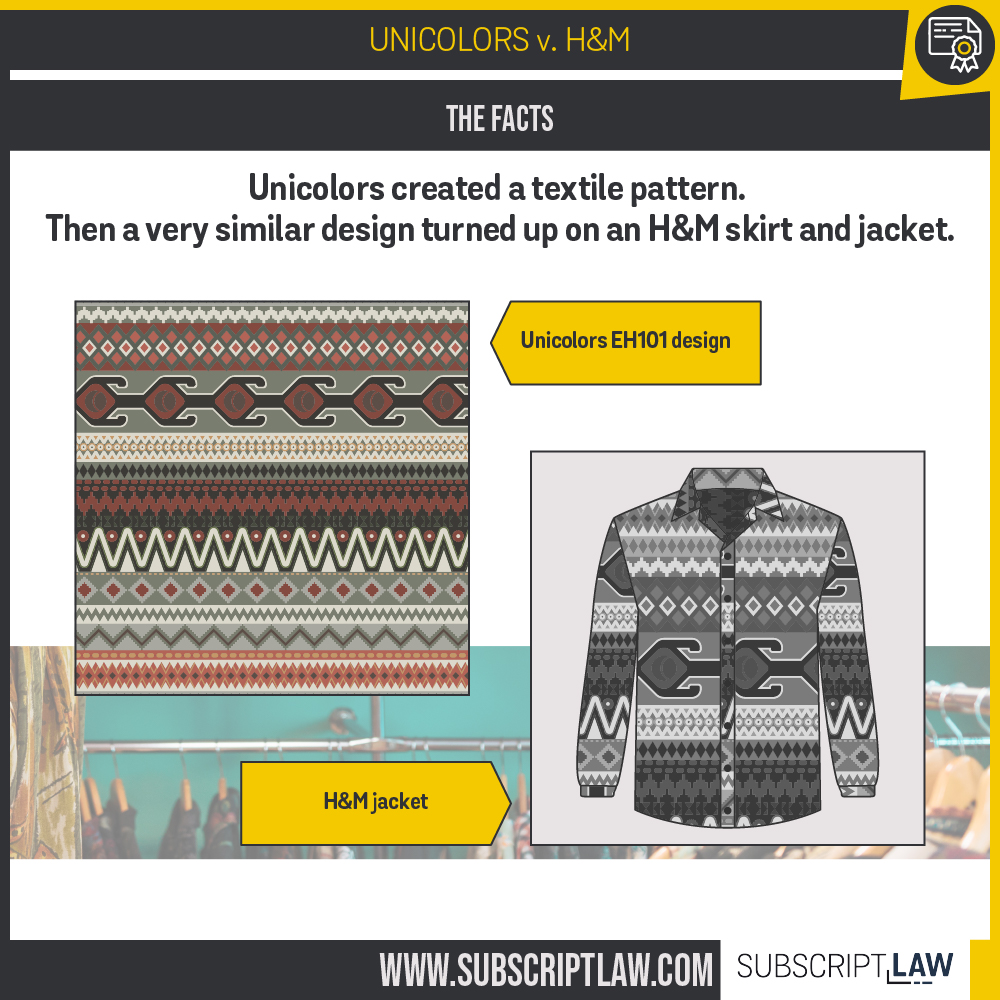

Unicolors is a Los Angeles-based company that designs and manufactures fabrics. In December 2010, Unicolors developed artwork for 31 fabric designs, including a design it identified as “EH101.” On January 15, 2011, Unicolors presented all 31 designs to its sales team. In February 2011, Unicolors filed all 31 designs, including EH101, in a single copyright application. The copyright application stated that all 31 designs were published on January 15, 2011. The Copyright Office subsequently issued one Registration Certificate, No. VA-1-770-400 (“’400 Registration”), covering all 31 designs in the collection.

H&M is a clothing retailer that operates hundreds of stores across the United States. In 2015, H&M began selling a jacket and skirt with a pattern similar to EH101. H&M received a letter from Unicolors accusing it copyright infringement in view of the ‘400 Registration.

Procedural Background

Unicolors sued H&M and a jury awarded Unicolors $800,000 in damages. The jury also found the infringement to be willful and awarded Unicolors over $500,000 in attorneys’ fees and costs.

Based on testimony presented during trial, H&M discovered that the 31 works listed in the ‘400 Registration were not all published on January 15, 2011. At least 9 of the fabric designs (although not EH101) were never published.

Under the US Copyright Act, a valid copyright registration is a precondition for bringing a copyright-infringement lawsuit. A suit may be initiated even if the registration includes inaccurate information, unless: (1) the inaccuracy was included “with knowledge that it was inaccurate,” and (2) the inaccuracy, “if known, would have caused the Register of Copyrights to refuse registration.” 17 U.S.C. § 411(b)(1).

The District Court Decision

In a post-trial motion, H&M argued that the ‘400 Registration was invalid because Unicolors used a single copyright application to register thirty-one separate works. For multiple designs to be included in a single application, they all must have been first sold or offered for sale in some integrated manner. However, at least 9 of the 31 designs in the ‘400 registration were not published on January 15, 2011. Therefore, the ‘400 Registration included information Unicolors knew was false and would have caused the Register of Copyrights to refuse registration.

The district court rejected H&M’s argument for invalidating the ‘400 Registration because even known inaccuracies only invalidate a registration if there is also evidence of intent to defraud the Copyright Office. No evidence of record showed Unicolors had such intent.

The Court of Appeals Decision

On appeal, the Ninth Circuit reversed, and held that that there is no intent-to-defraud requirement. Unicolors included the inaccurate information because it knew that 9 designs did not publish with the other 22 designs. The appeals court ordered the district court to request the Register of Copyrights to advise whether the inaccurate information provided by Unicolors would have caused the Register to refuse the ‘400 Registration.

The Question Before the Supreme Court

Unicolors petitioned and was granted certiorari on the question of whether the Copyright Act requires referral to the Register of Copyrights where there are no indicia of fraud associated with inaccurate information in a copyright registration.

Unicolors Arguments

Unicolors argues that it had a good faith belief that all 31 designs were “published” together because they were all presented to the sales team at the same time. Legally, presentation to the sale team may not qualify as publication because the salespeople are Unicolors employees, not the public. However, Unicolors thought that the presentation to the sales team did qualify as publication.

Because Unicolors made an innocent mistake, it did not have “knowledge” that the publication date it provided was “inaccurate.” Only an applicant who is either subjectively aware of an inaccuracy or willfully blind to an inaccuracy meets the “knowledge” standard.

Conventionally, ignorance of the law is not a defense. However, here the “knowledge” requirement defines a condition of mind. In such cases, ignorance or innocent mistake does negate the “knowledge” requirement of a threshold mental state.

The Copyright Act states that to qualify for referral to the Register of Copyrights, information must have been included in an application with “knowledge” the information was inaccurate. “Knowledge” in this context requires subjective awareness of the inaccuracy. In contrast, legal standards that require subjective awareness use modifiers like “constructive,” “presumed,” or “reckless.”

Unicolors also argues that “knowledge” in the Copyright Act was meant to codify the common law doctrine of “fraud on the Copyright Office.” Under the common law rule, only applicants that provide inaccurate information with an intent to deceive the Copyright Office will be denied the benefits of a copyright registration. The purpose of the common law rule was to prevent intellectual property thieves from escaping liability due to a clerical mistake in application documents. Likewise, Unicolors argues that its good-faith mistake cannot be a basis for challenging validity of the ‘400 Registration.

From a policy perspective, Congress did not intend to apply a rule that so severely overrides copyright holders’ rights and remedies. Copyright applications are often completed by creators who are not lawyers. These are not the type of people Congress would have wanted to punish for making innocent mistakes of law. Here, H&M’s argument is a pure technicality. It is arguing that the ‘400 registration is invalid only because Unicolors listed other works in the same application as EH101. Invalidating a copyright registration in view of such a technicality undermines protection artists expect as an incentive to create new works.

H&M Arguments

With respect to inaccurate information in a registration, the Ninth Circuit properly rejected any “intent-to-defraud” requirement. The plain meaning of “knowledge” is the fact or condition of being aware of something. It is well established that “knowledge” does not connote purpose or intent. Had Congress wished to require “intent-to-defraud,” it could have used terminology such as “fraudulent” or “deceptive.”

It was not well settled that the common law required “intent-to-defraud” to revoke an issued copyright registration. Court decisions predating enactment of the current Copyright Act articulated various formulations, including many that do not mention fraudulent intent.

Unicolors is now effectively raising a new question, by asking the Court to decide what the “knowledge” requirement means. The only question before the Court is whether “knowledge” requires fraudulent intent. The Court has not been asked whether a misunderstanding of law is safe harbor that saves an inaccuracy from being referred to the Register of Copyrights. This question not properly before the Court, and the Court should decline to address it.

Even if the Court addresses the “new” question presented by Unicolors, “knowledge” generally does not excuse mistakes of law. In the relevant section of the Copyright Act, Congress did not use any of the normal textual cues (e.g., “willful or “have knowledge that. . .”) that would excuse knowledge of the law.

Furthermore, even if the “knowledge” is construed to excuse mistakes of law, what matters is not the applicant’s subjective belief, but whether that belief was reasonable. Unicolors admitted during trial that the 31 designs were grouped together “for saving money,” not due to any belief about what the law required. Furthermore, showing a work to one’s own employee does not even reflect a plausible understanding of publication.

From a policy perspective, limiting “knowledge” to “factual knowledge” would seriously weaken the copyright registration system. It would mean that copyright applicants need not understand even the most basic copyright principles, including simple instructions on the application form.

The countervailing policy concerns suggested by Unicolors and the government are misplaced. Construing “knowledge” to include “legal knowledge” will not weaken copyright protection because a court cannot invalidate a registration unless the inaccuracy would have caused the Register of Copyrights to refuse registration. Trivial inconsistencies or typographical errors will typically not meet this standard. Even if a registration is invalidated, the applicant will not lose their copyright protection. They can simply re-register the work, albeit without the benefit of certain statutory remedies.

US Government Arguments

The US Government filed a brief in this case supporting Unicolors.

The Government argues that errors in a copyright registration do not invalidate a copyright registration unless the applicant included “inaccurate information” on the application “with knowledge” that the “information” was “inaccurate.” The “information” applicants submit as part of the application process includes applying law to fact. For example, to identify a publication date, the applicant must consider both the relevant law (what events count as “publication”) and the facts (when did those events occur).

Under the plain language of the Copyright Act, the term “knowledge” includes an applicant’s understanding of the relevant law that applies to the submitted “information.” Therefore, an applicant who believes “information” submitted on a copyright application is accurate cannot have acted “with knowledge” that the “information was inaccurate,” even if the inaccuracy was due to an erroneous legal interpretation.

In this case, if Unicolors’ misunderstanding of applicable law caused it to believe that the “information” it provided (e.g., the January 15, 2011 publication date) was the first date of publication for all 31 works, Unicolors did not have “knowledge” that “information” was inaccurate.

Construing “knowledge” in this way does not give applicants a free pass to claim ignorance of copyright law. For example, evidence of “willful blindness” may support a finding of “knowledge.” Other considerations, such as the well-settled nature of a legal requirement, a motive to include an inaccurate information, and the plausibility of asserted ignorance or mistake may all be relevant in establishing “knowledge.”

Other provisions of the Copyright Act refer specifically to circumstances where an actor should have been aware that a particular legal requirement is implicated (e.g., “reasonable grounds to know . . .,” “reasonable grounds to believe . . . .,” “not aware of facts or circumstances from which. . . is apparent”). The section of the statute regarding “inaccurate information” does not contain any such analogous language. When Congress includes particular language in one section of a statute but omits it in another, there is a presumption Congress intended a difference in meaning. Therefore, in the context of “inaccurate information,” “knowledge” means “factual” knowledge and not “legal” knowledge.

From a policy perspective, copyright applicants are generally not experts in either copyright law or procedures. Allowing copyright registrations to be invalidated when an applicant was unaware of or misunderstood legal rules undermines the purpose of the Copyright regime. Creators should be allowed to protect their copyrights from potentially unlawful use even if their registrations include legal inaccuracies arising from an understandable, although incorrect, understanding of the law.

The Court will hear oral argument in this case on November 8, 2021 and has granted the Government’s request to participate in the oral argument.

Facts of the Case (Oyez):

Unicolors, Inc., a company that creates art designs for use on fabrics, created and copyrighted as part of a collection of designs a two-dimensional artwork called EH101 in 2011. In 2015, retail clothing store H&M began selling a jacket and skirt with an art design called “Xue Xu.” Unicolors sued H&M for copyright infringement, alleging that the Xue Xu design is identical to its EH101 design.

The district court rejected H&M’s argument that Unicolors’ copyright was invalid because it had improperly used a single copyright registration to register 31 separate works. The court noted that invalidation of a copyright requires an intent to defraud, and no such evidence was presented in this case. Further, it concluded that the application contained no inaccuracies because the separate designs in the single registration were published on the same day. A jury returned a verdict for Unicolors, finding that it owned a valid copyright in EH101, that H&M had infringed on that copyright, and that the infringement was willful.

On appeal, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit reversed, finding that there is no intent-to-defraud requirement for registration invalidation, and the district court failed to refer the matter to the Copyright Office, as required under 17 U.S.C. § 411(b)(2), when it was informed of inaccuracies in the copyright registration.

Visit Oyez.

Question in the Case (Oyez):

Does 17 U.S.C. § 411 require a district court to request advice from the Copyright Office when there are questions about the validity of a copyright registration but no evidence of fraud or material error?

Visit Oyez.

Ninth Circuit Decision

BEA, Circuit Judge:

This is a copyright-infringement action brought by Unicolors, Inc. (“Unicolors”), a company that creates designs for use on textiles and garments, against H&M Hennes & Mauritz L.P. (“H&M”), which owns domestic retail clothing stores. Unicolors alleges that a design it created in 2011 is remarkably similar to a design printed on garments that H&M began selling in 2015. The heart of this case is the factual issue whether H&M’s garments bear infringing copies of Unicolors’s 2011 design. Presented with that question, a jury reached a verdict in favor of Unicolors, finding the two works at least substantially similar. On appeal, however, we must decide a threshold issue whether Unicolors has a valid copyright registration for its 2011 design, which is a precondition to bringing a copyright-infringement suit.

I

Unicolors’s business model is to create artwork, copyright it, print the artwork on fabric, and market the designed fabrics to garment manufacturers. Sometimes, though, Unicolors designs “confined” works, which are works created for a specific customer. This customer is granted the right of exclusive use of the confined work for at least a few months, during which time Unicolors does not offer to sell the work to other customers. At trial, Unicolors’s President, Nader Pazirandeh, explained that customers “ask for privacy” for confined designs, in respect of which Unicolors holds the confined designs for a “few months” from other customers. Mr. Pazirandeh added that his staff follows instructions not to offer confined designs for sale to customers generally, and Unicolors does not even place confined designs in its showroom until the exclusivity period ends.

In February 2011, Unicolors applied for and received a copyright registration from the U.S. Copyright Office for a two-dimensional artwork called EH101, which is the subject of this suit. Unicolors’s registration—No. VA 1-770-400 (“the ‘400 Registration”)—included a January 15, 2011 date of first publication. The ‘400 Registration is a “single-unit registration” of thirty-one separate designs in a single registration, one of which designs is EH101. The name for twenty-two of the works in the ‘400 Registration, like EH101, have the prefix “EH”; the other nine works were named with the prefix “CEH.” Hannah Lim, a Unicolors textile designer, testified at trial that the “EH” designation stands for “January 2011,” meaning these works were created in that month. Ms. Lim added that a “CEH” designation means a work was designed in January 2011 but was a “confined” work.

When asked about the ‘400 Registration at trial, Mr. Pazirandeh testified that Unicolors submits collections of works in a single copyright registration “for saving money.” Mr. Pazirandeh added that the first publication date of January 15, 2011 represented “when [Unicolors] present[ed] [the designs] to [its] salespeople.” But these salespeople are Unicolors employees, not the public. And the presentation took place at a company member-only meeting. Following the presentation, according to Mr. Pazirandeh, Unicolors would have placed non-confined designs in Unicolors’s showroom, making them “available for public viewing” and purchase. Confined designs, on the other hand, would not be placed in Unicolors’s showroom for the public at large to view.

H&M owns and operates hundreds of clothing retail stores in the United States. In fall 2015, H&M stores began selling a jacket and skirt made of fabric bearing an artwork design named “Xue Xu.” Upon discovering H&M was selling garments bearing the Xue Xu artwork, Unicolors filed this action for copyright infringement, alleging that H&M’s sales infringed Unicolors’s copyrighted EH101 design. Unicolors alleges that the two works are “row by row, layer by layer” identical to each other.

The case proceeded to trial, at which a jury returned a verdict in Unicolors’s favor, finding Unicolors owned a valid copyright in the EH101 artwork, H&M infringed on that copyright by selling the contested skirt and jacket, and H&M’s infringement was willful. The jury awarded Unicolors $817,920 in profit disgorgement damages and $28,800 in lost profits. H&M filed a renewed motion for judgment as a matter of law, or in the alternative, for a new trial. The district court denied H&M’s renewed motion for judgment as a matter of law, but conditionally granted H&M’s motion for a new trial subject to Unicolors accepting a remittitur of damages to $266,209.33. Unicolors accepted the district court’s remittitur and the district court entered judgment against H&M accordingly. Unicolors subsequently moved for attorneys’ fees and costs, which the district court awarded in the amounts of $508,709.20 and $5,856.27, respectively. This appeal of both the entry of judgment and award of attorneys’ fees in favor of Unicolors followed.

Read the full opinion on CaseText.

Summary of Argument (Brief of Petitioner)

Under § 411(b)(1)(A), a copyright registration applicant who includes inaccurate information on a registration form due to a mistaken understanding of the law does not have “knowledge” that the “information” is “inaccurate.”

A. The text of § 411(b)(1)(A) unambiguously requires a defendant challenging the validity of a registration certificate to prove that the applicant possessed awareness of an inaccuracy. In common parlance, if you ask someone whether they gave information “with knowledge that it was inaccurate,” that means, “Did you know it was wrong when you said it? Were you lying?” Both English and legal usage dictionaries define “knowledge” as a state of subjective awareness. By contrast, legal standards that depart from requiring proof of subjective awareness employ modifiers like “constructive” or “presumed,” or include language like “knew or should have known”—language Congress included elsewhere in the Copyright Act, but chose not to include in § 411(b)(1)(A).

Nothing in the statutory text suggests the Ninth Circuit’s distinction between inaccurate information included as a result of a mistake of fact and inaccurate information included as a result of a mistake of law. The words “inaccurate information” naturally encompass both. We know that is what Congress meant here because it used the term “information” to encompass both facts and legal conclusions in § 409, which provides a list of “information” that must be included on a registration application.

The text requires proof of “knowledge” that the “information” itself was inaccurate, not knowledge of surrounding or underlying facts or circumstances from which one could derive knowledge. That means that whether an inaccuracy results from an applicant’s mistake as to a historical event or real-world circumstance or as to how the law applies to those facts, the applicant does not have “knowledge” that the “information” is “inaccurate.”

B. The backdrop of common law provides further proof that the Ninth Circuit’s reading of § 411(b) is wrong. Section 411(b) codified the longstanding fraud-on-the-Copyright-Office doctrine, under which a good-faith mistake, whether of fact or law, cannot be a basis for challenging a copyright registration. Every circuit that analyzed the issue agreed that an inadvertent mistake was insufficient to invalidate a registration. No circuit suggested the Ninth Circuit’s distinction between factual and legal mistakes. And numerous cases rejected efforts to invalidate registrations on the basis of good-faith legal errors. “

When Congress codifies a judicially defined concept, it is presumed, absent an express statement to the contrary, that Congress intended to adopt the interpretation placed on that concept by the courts.” Davis v. Mich. Dep’t of Treasury, 489 U.S. 803, 813 (1989). The same presumption applies where a statute “covers an issue previously governed by the common law.” Kirtsaeng v. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 568 U.S. 519, 538 (2013) (internal quotation marks omitted). Far from clearly intending to depart from the common law, Congress clearly intended to retain it. This conclusion accords with Congress’s stated objective of closing loopholes that would prevent copyright enforcement; the general trend in the law away from requiring strict adherence to copyright formalities; and analogous doctrines in both patent and trademark law.

C. When a statute requires “knowledge” of a circumstance with both factual and legal components, a mistake of law is a defense. This Court has so held in various contexts where a good-faith mistake of law negates the state of mind required by a statute. The Ninth Circuit erred in ignoring these cases in favor of the maxim that ignorance of the law is no defense. That principle precludes a defendant accused of violating a statutory proscription from claiming that he was unaware of that proscription. But it has no application where, because of a collateral mistake of law, the defendant lacks the requisite state of mind—a well-recognized defense that plainly applies to § 411(b)(1)(A)’s requirement of “knowledge.”

D. Congress could not have intended to defeat the rights and remedies of copyright holders and instigate the mischief the Ninth Circuit’s approach invites.

Congress understood that mistakes on copyright applications are inevitable. Most applicants are laypeople, not copyright experts. Nettlesome questions of copyright law inevitably yield innocent legal errors on registration applications. Under the Ninth Circuit’s rule, these innocent mistakes would be penalized with devastating consequences. Because of the three-year statute of limitations, invalidating a copyright registration could prevent a copyright holder from ever remedying infringement. And even if a copyright holder could correct any error and re-file within the statute of limitations, two significant remedies—statutory damages and attorneys’ fees—would be unavailable in many cases.

These dynamics would also create perverse incentives in litigation, encouraging infringers to scour registrations for technical errors in hopes of using § 411(b)(1)(A) as a delay tactic or to blow up an adverse jury verdict. Meanwhile, the Copyright Office would be overwhelmed with referrals, many of them baseless, concerning whether a claimed inaccuracy is material. The Ninth Circuit identified no benefit that Congress might have hoped to achieve by allowing infringers to use technicalities to avoid liability. The equities of the Ninth Circuit’s reading of § 411(b) are so lopsided that Congress could never have intended them.

The decision below should be reversed.

Read the full brief.

Summary of Argument (Brief of Respondent)

In its petition, Unicolors asked this Court to decide whether Section 411(b) requires a showing of intent to de-ceive. It argued that, in direct conflict with the Ninth Cir-cuit, the Eleventh Circuit properly construed the statute to require not just knowledge, but “‘intentional or pur-poseful concealment of relevant information.’” Pet. Reply 6. In its merits brief, however, Unicolors no longer asks the Court to address that question. For good reason. The statute says nothing about fraud, and the Ninth Circuit properly rejected any “intent-to-defraud” requirement. See infra Part I.

Unicolors now wants the Court to answer a different question: What kind of knowledge does Section 411(b) re-quire? That new question, however, is not properly before the Court. See infra Part II.

On the actual question presented, the United States agrees with H&M. See U.S. Br. 25 n.5. But in what ap-pears to be a recent conversion, it agrees with Unicolors on the new question. The government’s change of heart cannot change the fact that the new question is not properly before the Court. Cf. Emulex Corp. v. Var-jabedian, 139 S. Ct. 1407 (2019) (dismissing petition as im-providently granted after the United States agreed with respondent on the actual question presented yet urged re-versal on the basis of a different, improperly presented question).

If the Court does address the new question, it should reject the mistaken interpretation of Section 411(b) ad-vanced by Unicolors and the government—limiting “knowledge” to subjective awareness of facts and law even if the applicant’s misunderstanding is manifestly unrea-sonable. At a minimum, the Court should hold that “knowledge” includes constructive knowledge of the law. See infra Part III.A. But, more fundamentally, there is no reason to think Congress intended to depart from the principle that “knowledge” refers to operative facts, not legal knowledge. See infra Part III.B. Affirmance is warranted.

Read the full brief.