Can the New York prosecutors get Trump’s financial information from Trump’s accounting firm?

In the United States Supreme Court

| Argument | May 12, 2020 |

| Decision | July 9, 2020 |

| Petitioner Brief | Trump |

| Respondent Brief | Vance, et al. |

| Opinion Below |  Second Circuit Court of Appeals |

Case Decision

On July 9, 2020, the Supreme Court ruled against President Trump. The NY Prosecutor can seek the president’s financial records for state criminal investigations.

Scroll down for our Decision Analysis.

May 11, 2019

On Tuesday morning, the Supreme Court will hear oral arguments about whether the President — and individuals and companies associated with him — are immune from state criminal investigation.

The New York grand jury subpoena

Public revelations about actions tied to Donald Trump caused the New York City District Attorney’s Office to open a grand jury investigation. The District Attorney sought to determine whether state law crimes had been committed in relation to efforts to silence porn star Stormy Daniels just before the 2016 Presidential election and to other behavior covered in testimony from Michael Cohen and others. Initially, the DA’s office (the DA is Cyrus Vance, Jr.) sent subpoenas to the Trump Organization, which cooperated for a time but balked at providing financial and tax records. In apparent response, new subpoenas were sent to Mazars USA LLP, the accounting firm for President Trump and for most if not all of the companies of which he is a direct or indirect owner. The subpoenas were very similar in form to subpoenas sent to the same accounting firm by Congressional committees and that are the subject of a separate case (Trump v. Mazars) before the Supreme Court. The records sought by the subpoena include years of financial and tax records of Donald Trump, Trump family members, and the many companies associated with them.

The subpoenas did not identify President Trump or any other person as the possible targets of the grand jury investigation.

Mazars indicated that it will comply with the subpoena if the federal courts do not invalidate it.

How did a state court subpoena end up in federal court?

The President’s lawyers filed suit in a New York federal court to challenge the subpoena, which relates to a state criminal proceeding. The suit asked the court to declare that the Constitution prohibits a state prosecutor from conducting a criminal investigation involving the President. Enforcement of the grand jury subpoena has been halted –stayed – throughout the proceedings, even though the President has lost at every level in the federal courts.

Rulings below

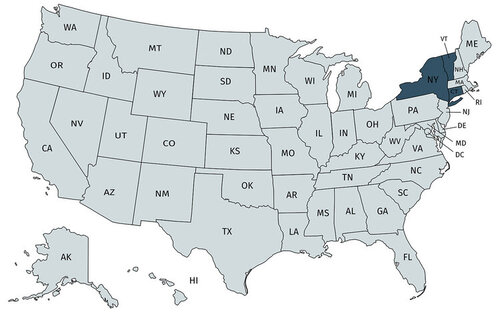

The President’s objections have been considered by both the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York and the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit. That appellate court ruled against the President in December, and the Supreme Court agreed to hear the case and the related Trump v. Mazars. The hearing was originally scheduled for the end of March but was delayed for about six weeks because of the COVID19 pandemic.

Does the president have absolute immunity from state criminal investigations?

Even though the subpoena to Mazars does not identify the President as a target of the grand jury investigation, the President made a number of arguments to the effect that allowing a state criminal investigation of the President would violate both Article II of the Constitution (which vests executive power in the President) and the Supremacy Clause of the Constitution (which makes federal law the supreme law of the land).

The President’s arguments describe the impracticability of allowing thousands of local prosecutors across the country to initiate criminal investigations and prosecutions of the President, and the interference that kind of behavior would cause with the President’s ability to perform his duties.

The response of the District Attorney has been to point out that the grand jury proceedings are secret, do not yet involve indictment or prosecution of the President, and are not necessarily directed at the President but may involve other individuals and companies to whom or which any Presidential immunity does not apply. The District Attorney has contended that the President does not have the level of immunity he claims, especially as to claims that have nothing to do with conduct of the President and others before becoming President. Moreover, both the District Attorney and the lower courts rejected the claim that responding to the subpoena would impair the President’s ability to perform his duties, noting that the subpoena is directed to an accounting firm. A request to a third party does not require any effort by the President to comply. Furthermore, every recent President has made substantial personal financial disclosures without impairment of their ability to function.

If there is Presidential immunity, can it prevent an investigation into possible criminal behavior by persons not the President?

The scope of immunity asserted by the President is breathtaking because it encompasses not only his own behavior, but also that of any other person, if investigating the conduct would “involve” the President. In effect, the President claims that he can confer immunity – potentially extending beyond the expiration of a statute of limitations – on any business colleague, employee, or affiliated company.

Unsurprisingly, neither the District Attorney not the lower courts have felt it necessary to devote substantial effort to refuting this line of argument.

Amicus argument: Most of the subpoenaed documents do not even belong to the President

In amicus curiae (“friend of the court”) briefs before the Court in Vance and Mazars, my colleague Sean Kealy and I present an argument ignored by the parties in the cases. We argue that President Trump cannot object to his accounting firm or banks turning over financial and tax information that actually does not belong to him. The information actually belongs to the more than 500 separate business entities connected to the Trump Organization.

President Trump argues that the records of these companies are “his” records and that the company tax returns are also “his.” However, the reason business owners form corporations and LLCs is to make sure they have liability protection by setting up separate legal persons – the companies – that insulate the individual owner from liability when something goes wrong. These companies are legally separate from their owners, and for decades, the President has steadfastly asserted this separateness in a variety of legal contexts. Under state law, records such as those covered by the subpoena belong only to the company, and so the President has no right to claim the companies should be protected from a subpoena because Trump doesn’t have an ownership interest at all in their content.

DECISION ANALYSIS:

Mariam Morshedi, July 10, 2020

Procedural Rights Are More Important Than a President’s Desire to Be Unbothered

On July 9, 2020, the Supreme Court declared that President Trump cannot shield his financial records from NY state prosecutors based on a claim of executive privilege. Justice Roberts wrote the opinion with support of the Court’s liberal wing, explaining that a President’s desire to be undisturbed in his executive duties does not overpower the Constitutional right to provide procedural rights to the accused.

The ruling did indicate, however, that President Trump may have other arguments to challenge the subpoenas. The case will return to the lower courts, where Trump may argue that the subpoena causes a specific conflict with his public duties or that the subpoena would “significantly interfere with his efforts to carry out” his duties.

Thus, while the President does not get a general, or absolute, exception to judicial processes seeking his personal information, if he can show that complying would actually (and specifically) impair his duties to function, he may have a case. In response to whether the NY prosecutors will have Trump’s information tomorrow, the answer is no.

Background

In the process of investigating potential state law violations, New York state prosecutors issued subpoenas to President Trump’s accounting firm. The records sought by the subpoena include years of financial and tax records of Donald Trump, Trump family members, and the many companies associated with them.

The subpoenas did not identify President Trump or any other person as the possible targets of the grand jury investigation.

President Trump challenged the subpoena in federal court. The lawsuit asked the court to declare that the Constitution prohibits a state prosecutor from conducting a criminal investigation involving the President. Trump argued the court should declare a sitting president absolutely immune from state criminal process, or at the least that a state criminal subpoena must meet a heightened standard of need in order to get information from a sitting president.

Mazars indicated that it will comply with the subpoena if the federal courts do not invalidate it.

The Supreme Court ruling

The Supreme Court ruled against President Trump’s arguments challenging the subpoena.

Justice Roberts opened the majority’s analysis by recounting the famous treason trial of Aaron Burr. That trial involved the enforcement of a subpoena directed at then-president Thomas Jefferson.

After killing Alexander Hamilton in a duel, Burr fled the northeast in search of new opportunities. Rumors started that Burr was engaged in a plan to separate states from the Union, and his political enemies sought to have him convicted for treason. Thomas Jefferson, then the president, was determined to have Burr convicted so Jefferson provided evidence purporting to show Burr’s involvement in a plot against the nation.

Burr’s legal team then issued a subpoena directed at Jefferson, requesting the president to produce a letter and accompanying documents which could shed light on Burr’s innocence. The prosecution claimed exception to the subpoena, arguing the President cannot be subject to the subpoena and that the letter requested could contain state secrets.

The Supreme Court ruled the President cannot claim exemption from the general provisions of the Constitution. The Constitution’s Sixth Amendment provides that the accused get procedural rights, which includes being able to obtain witnesses for their defense. A President, Chief Justice Marshall noted, is not a King, who is above the law. A President is “of the people” and subject to the law. And thus when he is asked to provide witness, he must comply.

In more recent history, Roberts recounted, Presidents generally comply with such requests. When Nixon refused to comply with the production of tape recordings of Oval Office meetings, the Supreme Court denied him.

President Trump claimed this case is different because this case involves state criminal proceedings, not federal proceedings. He claimed that he, as Chief Executive, cannot be forced to be provide information because the information could 1) distract him, 2) place a stigma on him, and 3) subject him to harassment, all in all inhibiting him from the performance of his executive duties provided in Article II of the Constitution.

The Court rejected each of these complaints in turn. Regarding whether responding to a subpoena could distract a president, it’s not enough, the Court ruled. Distraction alone wasn’t enough in Clinton v. Jones, and it wasn’t enough in Nixon v. Fitzgerald. Even if the president is the one under investigation, an argument that he may be distracted from his official duties is not enough to avoid compliance with judicial process.

Regarding Trump’s argument that the subpoena could place a stigma on him and impair his duties, the Court was not persuaded:

But even if a tarnished reputation were a cognizable impairment, there is nothing inherently stigmatizing about a President performing “the citizen’s normal duty of . . . furnishing information relevant” to a criminal investigation.

Regarding Trump’s argument that subjecting him to state criminal processes could subject him to harassment by state officials, the Court responded that both federal law and state processes have protections against such abuse. State grand jury investigations cannot engage in “arbitrary fishing expeditions”; nor can they initiate investigations “out of malice or an intent to harass.” The Constitution’s Supremacy Clause also protects the president from abuse by state judges and prosecutors. If the president suspects bad faith in the investigation, he may pursue other means of defense. But he cannot claim absolute immunity from state criminal process.

Further, the Court added, there is no heightened standard of need that a subpoena must satisfy in order to gain information from a sitting president. A heightened standard is reserved for official documents of the president; not for his private papers. A heightened standard would not help the president execute his duties any better. If the information of a president is relevant to a criminal investigation and satisfies the general standard, it’s the right of the investigators and the grand jury to seek it.

The Court concludes by noting that the President may still be able to fight the subpoena under grounds of interference with his public duties, but that this case only resolved whether he has an absolute executive privilege or a heightened standard of need — which he does not.

Concurrence: Justices Kavanaugh and Gorsuch

Kavanaugh and Gorsuch concurred in the majority opinion’s decision to deny the president absolute immunity, and they agreed that the case was not over (i.e. that the President still has a chance to prove that the state criminal process is interfering with his duties). However, the concurring justices would have addressed those additional arguments in the context of the case at-hand, rather than ordering that the arguments be raised separately in the lower courts.

Kavanaugh writes that he would have conducted an analysis from the 1982 case Nixon v. Fitzgerald, which required that the president show a “demonstrated, specific need” to avoid the subpoena. The majority opinion may allow the same type of showing, but the majority is requiring the president to raise a new claim in the lower courts to do so.

Dissent: Thomas

Justice Thomas dissented from the ruling. He agrees that the president does not have an absolute immunity from the issuance of a subpoena but that the president may be immune from the enforcement of the subpoena. Thomas believes the president should be able to argue against enforcement of the subpoena because the President’s “duties as chief magistrate demand his whole time for national objects.”

Dissent: Alito

Justice Alito dissented because he believes the majority opinion does not credit the President with enough distinction from the ordinary individual. Alito would institute a higher standard of need for subpoenas of the president, and he states clearly that a grand jury investigation involving the president is no ordinary grand jury investigation.