Officers Argue New Mexico Woman was Shot, Paralyzed, but Not Seized

| Argument | October 14, 2020 |

| Decision | March 25, 2021 |

| Petitioner Brief | Roxanne Torres |

| Respondent Brief | Janice Madrid; Richard Williamson |

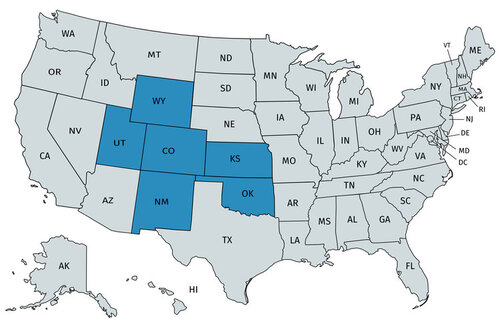

| Opinion Below |  Tenth Circuit Court of Appeals |

Case Decision

On March 25, 2021, the Supreme Court ruled for Torres, that “the application of physical force to the body of a person with intent to restrain is a seizure even if the person does not submit and is not subdued.”

Scroll down for our Decision Analysis.

Argument Analysis

October 12, 2020

In the dark early morning hours of July 15, 2014, Roxanne Torres dropped off a friend at an apartment building. Around the same time, New Mexico police officers Janice Madrid and Richard Williamson arrived in an unmarked car. They were in plain clothes and tactical vests with police indicia. The officers had an arrest warrant for a woman unrelated to Torres. Officers Madrid and Williamson saw Torres parked outside the building and approached the car. The officers reasoned that either Torres was the target of the warrant or knew something about the target.

Madrid and Williamson stood on each side of Torres’ car without identifying themselves as police officers. They repeatedly commanded Torres to “Open the door!” and “Show me your hands!” Torres neither heard the commands nor saw any indicia identifying Madrid and Williamson as police officers. All she saw were two strangers with guns and dark clothing trying to access her car—Torres thought Madrid and Williamson were carjackers.

When the officers tried to open the car door, Torres drove forward fearing for her safety. The officers believed Torres was going to hit them with the car. In self-defense, the officers drew their service weapons, aimed at Torres, and fired 13 gunshots as Torres drove away. Two bullets struck Torres’ body. One bullet pierced her back, paralyzing her arm.

Torres drove a short distance before colliding with another car. Torres laid down on the ground and asked a bystander to call 911. Believing the carjackers were still in pursuit, Torres took an unattended running car and drove to a hospital 75 miles away. Due to her injuries, Torres’ was airlifted to a larger hospital. The next day, the police arrested Torres at the hospital.

The Fourth Amendment

The Fourth Amendment confers a right upon people “to be secure in their persons . . . against unreasonable searches and seizures.” Seizure applies in two ways. One way is through the application of physical force to a person’s body. For example, placing handcuffs on a person. Seizure also applies when a show of authority causes a person to submit. For example, when a law enforcement officer commands “stop,” and the person stops.

All seizures must be reasonable. The reasonableness standard is a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma. The standard employs the perfectly “reasonable person”—a fictional character created by the judiciary. A seizure is likely reasonable when there is an arrest warrant. Warrantless seizures may be reasonable when there are exigent circumstances, evidence that is in plain view, consent, or probable cause for a person’s arrest.

Excessive use of force may deem the seizure of a person unreasonable. Force is excessive when it is greater than what is reasonably necessary to detain someone or make an arrest. Circumstances dictate whether the use of lethal force was reasonable when seizing a person. For instance, while an officer may not shoot an unarmed suspect fleeing on foot, an officer may shoot a suspect fleeing in a car that is about to run them over.

Was the Force Excessive?

Section 1983 of Title 42 of the United States Code (42 U.S.C. § 1983) allows a person to sue law enforcement officers for excessive use of force. Law enforcement officers may be held personally liable for damages when they violate constitutional rights, such as the Fourth Amendment. The judicially created doctrine of “qualified immunity” protects officers from personal liability. Qualified immunity is neither written in the Constitution nor established by Congress. The Doctrine protects public employees from being sued and held personally responsible for injuries caused in the normal course of their duties as long as they did not knowingly violate “clearly established statutory or constitutional rights.”

On October 21, 2016, Torres sued officers Madrid and Williamson under Section 1983 for use of excessive force. The officers filed a motion for summary judgment stating an excessive force claim requires a seizure. They argued that since Torres fled, they never seized her. Therefore, Torres cannot have an excessive force claim. The trial court agreed and granted the officers’ motion. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the 10th Circuit affirmed the decision that the officers did not seize Torres. Torres asked the Supreme Court to hear her case, and the Supreme Court granted her petition.

What Constitutes a Seizure?

In Terry v. Ohio (1968), the Supreme Court noted that “not all personal intercourse between policemen and citizens involves ‘seizures’ of persons. Only when the officer, by means of physical force or show of authority, has in some way restrained the liberty of a citizen may we conclude that a ‘seizure’ has occurred.”

In California v. Hodari D. (1991), the Supreme Court held that a “seizure” requires either physical force or submission to police authority. Since then, appellate courts have disagreed on the meaning of “submission” in the context of police authority. The Supreme Court did not find that a seizure occurred in Hodari D. when officers chased a suspect without making any contact because an “arrest requires either physical force . . . or, where that is absent, submission to the assertion of authority.” The Court found that “[t]he word ‘seizure’ readily bears the meaning of a laying on of hands or application of physical force to restrain movement, even when it is ultimately unsuccessful.”

The D.C. and First Circuits say that encounters similar to Torres’, where there is temporary compliance to a show of authority followed by flight, may constitute submission. The Second, Third, Ninth, and Tenth Circuits contend that compliance followed by flight is not submission.

This case presents an opportunity for the U.S. Supreme Court to resolve the circuit split over the definition of “submission to police authority.”

The Case for Torres

Despite her temporary escape, Torres contends she eventually submitted to police authority and that officers Madrid and Williamson seized her when they shot at her 13 times, striking her twice.

The application of force with the intent to restrain constitutes seizure. The Fourth Amendment protects peoples’ right to be “secure in their persons.” Unless justified, any bodily intrusion violates the Fourth Amendment. Cheek swabs, blood draws, fingernail scrapings, and breathalyzer tests require probable cause. All of them are significantly less intrusive than intentionally shooting at a person and striking them.

Officers Madrid and Williamson shot at Torres with the intent to restrain her, striking her twice and paralyzing her arm. Here, the Supreme Court precedent in Hodari D. applies: “[t]he word ‘seizure’ readily bears the meaning of a laying on of hands or application of physical force to restrain movement, even when it is ultimately unsuccessful.” The shooting constituted a seizure, even when Torres continued to drive away.

If seizure requires a restraint on movement, then the officers seized Torres. The bodily injury caused by the officers’ bullets, paralyzing Torres’ arm, restrained her movement and forced her to stop to seek medical attention. The eventual stop is a submission to police authority resulting from the lethal physical force used by officers Madrid and Williamson.

Unreasonable physical force used in a seizure violates the Fourth Amendment. This seizure was unreasonable because Madrid and Williamson used lethal and excessive force when they shot at Torres 13 times. The officers were standing at the side of the car and no one was in imminent danger of being run over as Torres drove away.

People trust law enforcement officers because they are held accountable by the Fourth Amendment. When violated, they are personally liable for damages. The judicial doctrine of qualified immunity offers protection against personal liability and ensures there are no impediments for law enforcement officers to discharge their duties so long as they exercise reasonable use of force. Here, a reasonable person may find Torres in submission and seized by the gunshots, even if she was able to escape from the shooters who she thought were carjackers.

The Case for Officers Madrid and Williamson

Without physical restraint or submission to police authority, there can be no seizure. Without a seizure, there can be no violation of the Fourth Amendment. Without a constitutional violation, officers Madrid and Williamson cannot be liable for any damages.

The Supreme Court precedent in Hodari D. and Terry v. Ohio clearly state that a seizure requires (1) restraint on a person’s liberty, even if followed by flight; or (2) submission to authority—regardless whether voluntary or involuntary. There is no seizure when a person does not stop.

First, officers Madrid and Williamson did not seize Torres because they did not physically restrain her. Torres did not respond to any verbal commands and drove away from the officers, unencumbered. Not only did Torres flee the scene, but she drove more than 75 miles away.

Second, the gunshots directed at Torres by Madrid and Williamson, including the two that struck her, did not cause Torres to submit to police authority. Instead, she continued to drive away. The force used by the officers was reasonable and proportional to the danger of being run over by Torres as she drove away. The officers responded in fear of their lives when Torres nearly ran them over. Had Torres stopped immediately after being shot, terminating her movement, then a reasonable person may have likely considered her seized for purposes of the Fourth Amendment. She neither stopped, nor was her movement terminated by the gunshots.

Torres’ conduct and account of the incident show that she felt free to leave and that she did not perceive herself as being seized by the officers’ gunshots. At no point did the officers take possession, custody, or control of Torres and at no point did Torres submit to police authority. Therefore, the officers did not seize Torres.

What is at Stake?

The 42nd Congress enacted Section 1983 to hold government officials personally responsible for upholding constitutional rights. Since then, the Court has largely promoted deference to politically accountable bodies. It even developed judicial doctrines that left victims of police violence and abuse with no realistic chance of recovery. Affirming the Tenth Circuit’s holding will further add to the already high barrier excessive force claimants must overcome to prevail.

Law enforcement officers enjoy unparalleled protections from accountability. They have powerful police unions, the “blue wall of silence,” free legal representation, sympathetic prosecutors, and reluctant juries. Police officers and the municipalities that employ them also have Supreme Court jurisprudence that is heavily tilted in their favor. With doctrines like “qualified immunity” and legal interpretations that favor police, such as the Torres case, the courts have afforded police officers with nearly complete immunity for their actions.

The Supreme Court constructed the legal doctrine of qualified immunity in 1967. During those years, police violence and use of lethal force against civil rights groups and activists were widespread. In Pierson v. Ray (1967), the Supreme Court responded by extending police officers the benefit of the doubt for enforcing the law “in good faith and with probable cause”—a high barrier to overcome.

The Court then made it nearly impossible for excessive force claimants to prevail by requiring any violation of rights be “clearly established”—another judicially constructed doctrine. That means, for a plaintiff to prevail, another court must have previously encountered a case that is similar in all respects, where the officer was found not immune.

The question before the Court is whether the use of lethal force to restrain a suspect constitutes a “seizure” under the Fourth Amendment, even if the force does not terminate the person’s movement or result in physically restraining the suspect.

Police shoot people to physically restrain and seize them. There should be no limit or precondition for a court to examine the justification of a shooting under the Fourth Amendment. Inquiring whether a particular bullet succeeded in immediately stopping a suspect is a condition that limits judicial inquiries to police shootings that results in fatalities or paralysis. A police officer’s bullet is an undeniably severe bodily intrusion. A person’s movement after being shot by the police should have no bearing in the seizure analysis. Resisting or escaping capture, detention, or arrest after being shot should not dictate whether the Fourth Amendment applies.

In the “Rights of Man,” Thomas Paine concluded that no one should trust “[a] body of men [that hold] themselves accountable to nobody.” The Supreme Court may not have the prerogative to address the longstanding structural roots of police violence against civilians. However, the Supreme Court has a duty in our tripartite government to upend the exploitative and discriminatory culture that has led to less police accountability.

The jurisprudence surrounding police violence and use of excessive force communicate to poor people and people of color that their lives are dispensable. The courts are the final salve for beleaguered communities that lack political influence, suffer the most violence at the hands of the police, and are treated with a punitive and unforgiving system. Policing neither exists in a vacuum, nor is it severed from its history. Policing is another tool in the social order that exacts, extracts, and exploits poor communities, contributing to cyclical violence and enshrining the dispensability of poor civilian lives, especially people of color. The courts should review cases such as Torres accordingly.

Affirming the Tenth Circuit’s holding does not only continue the Court’s trajectory in shielding law enforcement officers from liability, it would even bar the basic reasonableness inquiry into the force used by police officers. Under the Tenth Circuit rule, only the fatal use of force would involve the Fourth Amendment. Adding another barrier for excessive force victims to overcome renders the constitutional accountability in Section 1983 obsolete. In affirming the Tenth Circuit holding, the Court risks becoming what Justice Benjamin Curtis in Dred Scott v. Sandford (1857) decried: a body that has “abandoned the fixed rules which govern the interpretation of laws” and is controlled “by individual men, who for the time being have power to declare what the Constitution is according to their own views.”

The Justices will hear arguments on October 14, 2020.

Decision Analysis

On March 25, 2021, the Supreme Court ruled for Roxanne Torres. Torres was shot 13 times by plain-clothed police officers as she drove away from them, believing they were carjackers. Two of the bullets struck her in the back. Torres sued the officers under 42 U. S. C. § 1983 for damages, claiming the officers violated the Fourth Amendment by using excessive force and unreasonably seized with their gunshots. The officers argued that Torres’ flight after being shot does not constitute a seizure. The District Court and Tenth Circuit agreed with the officers.

Does the use of lethal force to restrain a suspect constitute a “seizure” under the Fourth Amendment, even if the force does not terminate the person’s movement or result in physically restraining the suspect?

In a 5-3 ruling, the Supreme Court held “the application of physical force to the body of a person with intent to restrain is a seizure even if the person does not submit and is not subdued.” The holding offers a two-pronged rule in determining that a seizure requires (1) the use of force (2) with an intent to restrain. The Court added that the application of physical force “can be as readily accomplished by a bullet as by the end of a finger.”

The Court found the test proposed by the officers—intentional acquisition of control—unsupported by the history of the Fourth Amendment and by the Court’s precedents. There is a difference between seizures by control and seizures by force. Each type of seizure requires a separate rule. Seizure by intentional acquisition of physical control “involves either voluntary submission to a show of authority” or “the termination of freedom of movement.” Imputing a control requirement to seizures by force has “yield uncertainty” and inconsistent results in the lower courts. The rule in Torres will offer guidance on seizures by force.

Chief Justice John Roberts, who authored the majority opinion, clarified that the Court only decided that “the officers seized Torres by shooting her with intent to restrain her movement,” vacating the Tenth Circuit’s ruling. The Court left open on remand “any questions regarding the reasonableness of the seizure, the damages caused by the seizure, and the officers’ entitlement to qualified immunity.”

While the lower courts will likely grant the officers qualified immunity, the Supreme Court’s decision for Torres is a significant win for litigants seeking police accountability in that it does not add to the already high barriers excessive force claimants must overcome.

Justice Neil Gorsuch wrote for the dissent, claiming the majority opinion is “as mistaken as it is novel.” He added that the Court’s decision makes a police encounter a seizure “even if the suspect refuses to stop, evades capture, and rides off into the sunset never to be seen again.”

Chief Justice Roberts was joined by Justices Stephen Breyer, Sonia Sotomayor, Elena Kagan, and Brett Kavanaugh. Justice Neil Gorsuch was joined by Justices Clarence Thomas and Samuel Alito. Justice Amy Coney Barrett did not participate.