Is discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation or gender identity sex discrimination?

In the United States Supreme Court

| Arguments | October 8, 2019 |

| Decision | June 15, 2020 |

| Briefs on Sexual Orientation | Altitude Express v. Zarda Bostock v. Clayton County, Georgia |

| Briefs on Gender Identity | R.G. & G.R. Harris Funeral Homes v. EEOC/Stephens |

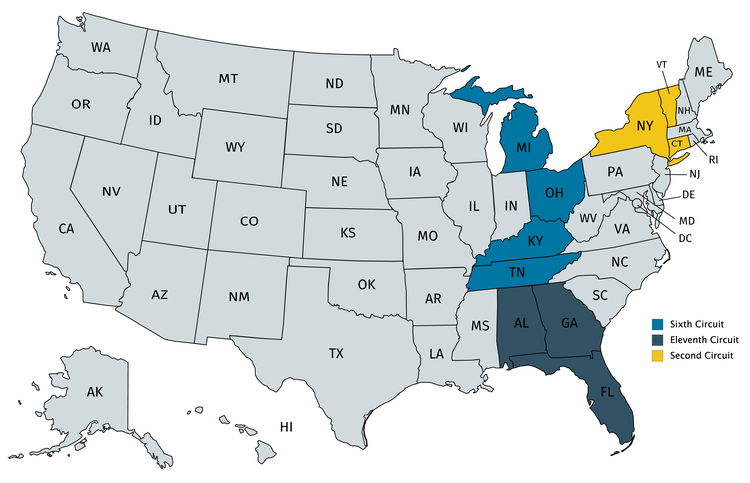

| Opinions Below |  Second Circuit opinion Eleventh Circuit opinion Sixth Circuit opinion |

Case Decision

On June 15, 2020 the Supreme Court ruled in favor of the employees. Employers cannot discriminate against workers for being gay or transgender.

Scroll down for our Decision Analysis.

October 7, 2019

The Supreme Court is set to hear three cases this term to decide whether Title VII’s protections against sex discrimination include discrimination based on sexual orientation or gender identity.

Key Terms

What is sexual orientation? A person’s sexual orientation refers to the sex or gender of the people that a person is romantically and sexually attracted to. The most common sexual orientations are heterosexual (an attraction to people of a different sex), homosexual (an attraction to people of the same sex), and bisexual (an attraction to people of both the same and different sexes). We all have a sexual orientation.

What is gender identity? Gender identity refers to a person’s internal sense of where that person falls on the gender spectrum—female, male, nonbinary, somewhere else on the spectrum. We all have a gender identity and we convey it to the world through our clothing, hairstyle, and other features. If a person’s internal sense of gender identity and the sex assigned to the person at birth (based on external sex organs) are the same, the person’s gender identity is cisgender. If a person’s internal sense of gender identity and the sex assigned to the person at birth are different, the person is transgender (commonly written as trans or trans*).

What is sex stereotyping? Sex stereotyping is the overgeneralization of how a man or woman should dress or act, and what kinds of jobs and roles they should hold within families and society. The concept of sex stereotyping first entered the legal world through the Supreme Court’s decision in Price Waterhouse v. Hopkins. In that 1989 decision, the Court held that Price Waterhouse’s decision not to promote Ms. Hopkins to partner because she was not sufficiently feminine was a form of sex discrimination prohibited by Title VII.

Title VII and the EEOC

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 prohibits discrimination “against any individual … because of such individual’s … sex.” Until 2012, the general understanding in the legal community was that sex referred only to biological sex—in other words, whether a person is male or female.

In 2012, the EEOC held in Macy v. Department of Justice, that discrimination based on gender identity is sex discrimination. The Commission reached this conclusion by finding that gender identity discrimination may involve sex stereotyping, that a “real” woman should be born with certain reproductive organs, and that is a form of prohibited discrimination.

Three years later, the Commission held in Baldwin v. Department of Transportation that sexual orientation discrimination is a form of sex discrimination. The EEOC found this type of discrimination falls within the coverage of Title VII for three reasons: first, sexual orientation can only be defined by taking into account the sex of the employee and therefore is connected to sex. Second, sexual orientation discrimination is a form of associational discrimination. The Commission drew a parallel to the Supreme Court’s decision in Loving v. Virginia, in which it struck down state laws that barred interracial marriage. And third, the EEOC found that sexual orientation discrimination is a form of sex stereotyping, as it relies on the idea that a man should only be interested in dating women, and a woman should only be interested in dating a man.

Why aren’t the Macy and Baldwin decisions the end of the question? The Commission’s decisions only address the rights of federal employees. The cases before the Supreme Court this term involve employees working for private companies and a county government.

The Cases

The Court has consolidated Altitude Express, Inc. v. Zarda and Bostock v. Clayton County, Georgia for arguments and decisions. Both cases address the issue of sexual orientation discrimination. In Zarda, the Second Circuit held that sexual orientation discrimination is covered by Title VII’s prohibition against sex discrimination. Just as the EEOC did, the Second Circuit found that sexual orientation cannot be defined without reference to sex. Relying on the Supreme Court’s decision in Oncale v. Sundowner Offshore Services, Inc., the Second Circuit concluded that if the employer takes the action because of sex, the action falls within Title VII’s protections, and if sexual orientation cannot be defined without taking sex into account, an action taken because of an employee’s sexual orientation is an action taken because of the employee’s sex. In Bostock, the Eleventh Circuit concluded that it was bound by prior circuit precedent, from 1979, finding that sexual orientation does not fall within Title VII’s definition of sex.

The Court is also set to hear arguments in R.G. & G.R. Harris Funeral Homes v. EEOC. In that case, the Sixth Circuit held that discrimination based on gender identity is sex discrimination. The circuit court reached this in two ways. First, it held that gender identity discrimination is a form of sex stereotyping. Second, the court held that gender identity cannot be defined without taking sex into account—whether through simply defining the employee’s sex or by taking into account the change in the employee’s sex from birth-assigned sex to expressing the person’s true gender identity.

The Arguments

The employees in all three cases have argued that their employers violated Title VII when they fired them. They argue that discrimination based on sexual orientation or gender identity inherently takes the employee’s sex into account and therefore is discrimination “because of . . . sex.” They also argue that these forms of discrimination are instances of sex stereotyping, which the Court concluded was a violation of Title VII 30 years ago. They also argue it’s immaterial that Congress may not have considered sexual orientation or gender identity in 1964, because the Court concluded in Oncale that the correct question is not whether Congress contemplated the specific facts—in that case, same-sex sexual harassment—but rather whether the action occurred because of sex.

The employers all argue that finding that Title VII prohibits discrimination based on sexual orientation or gender identity is an impermissible and inappropriate expansion of Congress’s intent in passing Title VII. The U.S. government has filed briefs in these cases arguing that Title VII does not apply to either sexual orientation discrimination or gender identity discrimination.

The Supreme Court will hear arguments on October 8, 2019.

DECISION ANALYSIS:

June 17, 2020

“An employer who fires an individual merely for being gay or transgender violates Title VII.”

On June 15, 2020 in three cases consolidated cases, the Supreme Court held that Title VII’s prohibition of discrimination based on sex protects lesbian, gay, and trans employees.

Background

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 explicitly prohibits employment discrimination “because of . . . sex.” In three consolidated cases before the Supreme Court this term, the justices considered whether discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation or gender identity is sex discrimination, or whether those two categories are separate from sex, and therefore not covered by Title VII.

In Altitude Express, Inc. v. Zarda, Altitude Express fired Mr. Zarda after Zarda told a client that he was “100% gay.” The Second Circuit held that sexual orientation cannot be defined without taking sex into account, and therefore discrimination based on sexual orientation is sex discrimination. In contrast, the Eleventh Circuit found in Bostock v. Clayton County, Georgia that it was bound by a 1979 case that found that sexual orientation is not covered by Title VII. It held that it therefore could not rule for Mr. Bostock, who the county had fired after he joined a gay softball team.

The Court also considered the Sixth Circuit’s decision in R.G. & G.R. Harris Funeral Home v. EEOC, in which the EEOC challenged the funeral home’s decision to fire Ms. Stephens after she disclosed that she was a transwoman and planned to begin dressing in feminine clothing to match her gender identity. The circuit court concluded that gender identity discrimination is a form of sex stereotyping, and that gender identity cannot be defined without considering an individual’s sex, making gender identity discrimination a form of sex discrimination.

The majority opinion

Justice Gorsuch authored the majority opinion and was joined by Chief Justice Roberts, and Justices Ginsberg, Breyer, Sotomayor, and Kagan. The Court held that it must consider the “ordinary public meaning” of the words Congress used in Title VII. The majority reasoned that the ordinary meaning of the word “sex” is being either male or female. The majority used a series of hypotheticals to illustrate how discrimination based on sexual orientation or gender identity turns, at least in part, on the sex of the employee, and therefore is discrimination because of sex.

For example, the Court considered a company that has a policy of firing gay or lesbian employees because of their sexual orientation. In the hypothetical, the company has a model employee with whom the company has no issues. The model employee then introduces a woman as the employee’s spouse at a company party. The question of whether the employer will fire the model employee turns on the employee’s sex. If the model employee is a man, the company will not take any action. If the model employee is a woman, the company will fire her based on its policy of not employing anyone who is a lesbian. The Court noted that although the company’s intention is to fire the model employee because of the employee’s sexual orientation, the company must intentionally treat the employee worse because of her sex in order to achieve its goal. Ultimately, because an employer cannot act based on an employee’s sexual orientation or gender identity without considering the employee’s sex, the application of the sex discrimination prohibition in these circumstances is nothing more “than the straight-forward application of legal terms with plain and settled meanings.”

The majority also considered the arguments of the employers and concerns of the dissenting justices and found they did not alter the ultimate conclusion that the plain meaning of Title VII prohibits discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation or gender identity. The majority rejected the argument that Congress clearly did not intend to cover sexual orientation or gender identity in 1964, and could have done so later by passing one of the bills proposing to amend Title VII that Congress has considered in more recent years. The Court found although few people in 1964, including the members of Congress who voted for Title VII, may have believed that the statute covered sexual orientation or gender identity as part of sex, that is immaterial. The fact that a result may be unexpected does not mean it is not correct under the plain meaning of the statute. The Court also found that looking to the intentions of a later Congress that chose not to alter a statute is not the appropriate analysis to determine the ordinary meaning of the existing law.

Finally, the Court was not persuaded by the broader concern that the ruling might impact other issues, such as the use of bathrooms and locker rooms, and the impact of the ruling on religious employers. The majority noted that those issues were not before the Court in the consolidated cases and may be addressed if, and when, they are raised in other cases.

The dissenting opinions

Justice Alito, in an opinion joined by Justice Thomas, dissented from the Court’s decision. Justice Alito rejected what he viewed to be the majority’s attempts to cloak its decision in textualism—interpreting the law based on the ordinary meaning of the text—and wrote that the majority was issuing legislation instead. He asserted that if Congress intended to expand Title VII to include protections based on sexual orientation or gender identity, it would have done so through bills it considered as recently as last year. He also concluded that the ordinary meaning of sex plainly does not encompass sexual orientation or gender identity, and cited to numerous dictionary definitions to illustrate the point. Finally, Justice Alito warned that the Court’s decision will “threaten freedom of religion, freedom of speech, and personal privacy and safety,” and that the majority improperly dismissed these concerns.

Justice Kavanaugh filed a separate dissenting opinion. In it, he concluded that it is for Congress, and not the Court, to amend Title VII and that as written, the statute does not prohibit discrimination based on sexual orientation or gender identity. Justice Kavanaugh also wrote the majority incorrectly considered the “literal meaning” of the word sex, and not the ordinary meaning, resulting in an incorrect interpretation of the statutory language.

The impact

LGBTQ advocacy groups often raised the concern that an employee could get married on Sunday and be fired on Monday when an employer learned of the employee’s sexual orientation. Before the Bostock decision, LGBTQ employees of private companies lacked protections in more than half of the country. Now LGBTQ employees are protected against discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity nationwide.

Correction: An earlier version of this report misspelled Contributor Meghan Droste’s last name.