What are sanctuary cities?

Sanctuary cities are local governments that refuse to help the federal government enforce immigration policy.

The tug-of-war

The federal government and sanctuary cities are in a tug-of-war power struggle.

The federal government aims to get local government agents working to enforce immigration law, i.e. to have local police on the lookout for potential immigration violations. Sanctuary cities don’t want to participate. They believe enforcing immigration law will harm residents’ cooperation with local government.

The laws relating to sanctuary cities

The American legal structure sets the rules of the game. What are the elements of the federal government and sanctuary cities’ leverage?

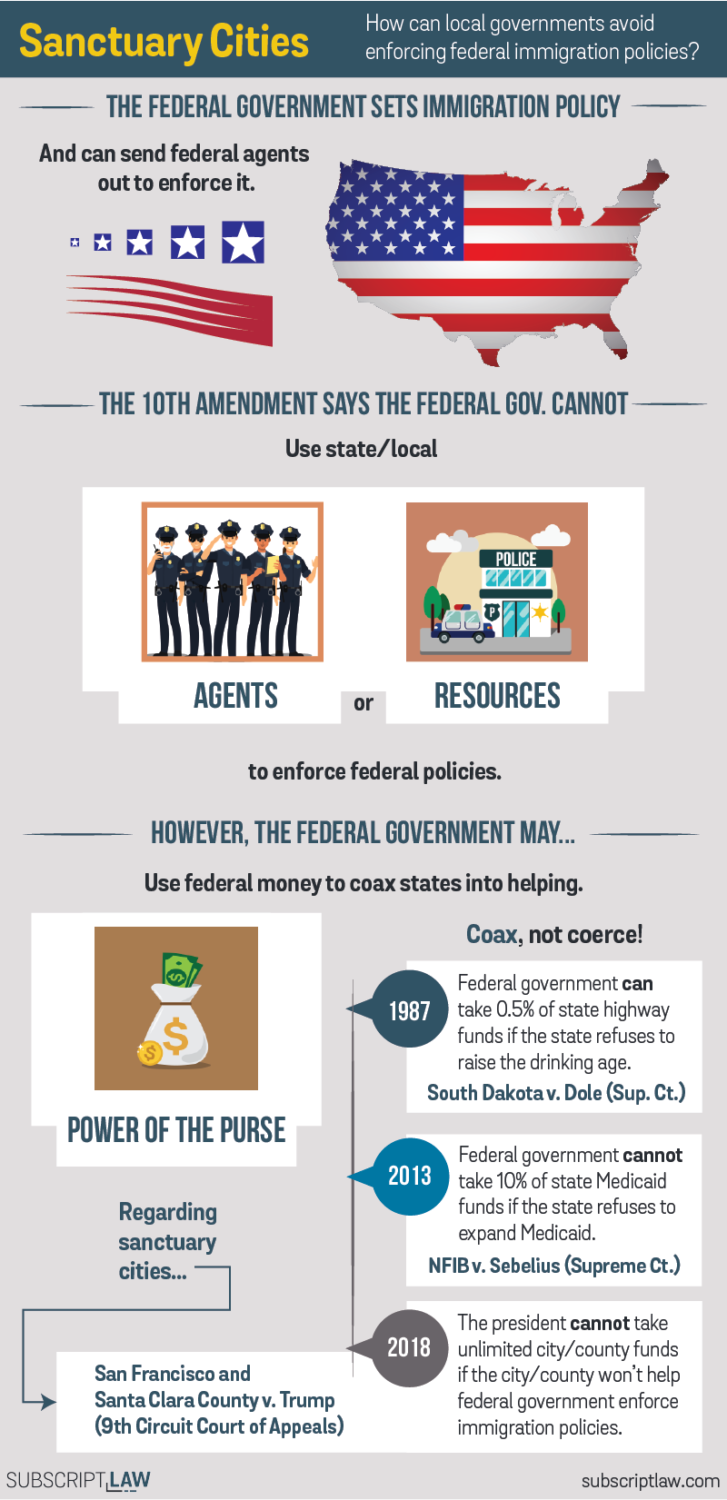

To explain how sanctuary city law works, we have produced an Infographic and a Legal Landscape.

Infographic

Legal Landscape: Sanctuary Cities

Outlining the relevant laws by legal authority

Constitution • Congress • Executive • Federal Courts • State Governments

The Constitution

The Constitution gives Congress the general power to legislate (Article I). It specifically mentions that this power includes creating laws on “naturalization” (Section 8, clause 4), i.e. defining immigration categories and providing procedures on entry and on deportation. See Legislative column below for some of the laws Congress has made relating to immigration.

The 10th Amendment says that the federal government cannot “commandeer” (boss around) the state governments. Basically, the federal government can create laws in certain categories (those listed in the Legislative Powers part of the Constitution), but it cannot force the states to help enforce them. This means states don’t have to use state or local resources (money or people that work for the state or local governments) to enforce federal policies.

The Spending Clause of Article I, Section 8 gives Congress the power to control the federal budget. The federal government is tasked with providing for the welfare of the people, so it sets aside money for certain programs that it decides will provide a public benefit. Sometimes, Congress gives the money for a particular program to state governments, so that the states can “administer” (do the legwork for) the programs. Because of the 10th Amendment, the states always have the choice whether or not to participate. The Medicaid program is an example of a federal program administered by the states. A couple other examples relevant to immigration enforcement are discussed in the Legislative column below (left). Here is a useful general discussion of federal grants to states.

Congress

The following federal laws (a non-exhaustive list) relate specifically to immigration.

The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952 governs immigration to and citizenship in the United States. It was signed in the context of the Cold War and in the scare of the spread of Communism. The Act established a preference system which determined which ethnic groups were desirable immigrants and placed importance on labor qualifications.

The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 revised several aspects of the 1952 law. Passed during the civil rights movement, it outlaws discrimination against people seeking immigration status (eliminated national origin, race, and ancestry as bases for immigration). Among its other provisions, it gave priority to relatives of U.S. citizens and legal permanent residents and to professionals and other individuals with specialized skills, and it allowed U.S. organizations to employ foreign workers either temporarily or permanently to fulfill certain types of job requirements (on visas such as the H-1B Visa).

The Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act of 1996 placed rules restricting the rights of people who stayed in the U.S. unlawfully for a period of time. Among its other provisions, it made people eligible for deportation based on minor criminal offenses (like shoplifting). The Act also includes a provision that is at issue in regards to Sanctuary Cities:

- 8 U.S.C. Section 1373 requires state and local governments to communicate with federal authorities regarding immigration-related information of individuals.

8 U.S.C. Section 1373 has limited power on its own. It cannot actually force the states to use their own resources (state law enforcement agents or state money) on federal priorities like immigration. The 10th Amendment does not allow it. However, in conjunction with a federal grant program, it can have more effect on state and local governments. This is the federal government’s Spending Power. It is also called “attaching strings” or the “power of the purse.” The federal government can offer money to states with the condition that the states follow certain rules. The conditions have to be clear; they cannot be coercive. States do not have to participate.

Congressionally-Established Federal Grant Programs:

Usually conditions on grants are set when Congress establishes the grant program. Sometimes Congress establishes grant programs and allows a federal agency to deal with the specifics. For example, Congress gave to the Department of Justice administration of the following programs:

The Edward Byrne Justice Assistance Grant Program gives federal money to state and local governments to help in their criminal justice efforts. It was funded by the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2005.

The State Criminal Alien Assistance Program reimburses state and local governments for costs of incarcerating unauthorized immigrants. It was funded by the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994.

See the Executive below for a discussion of Department of Justice potential to enforce federal law through administering a federal grant program.

The President and Executive Agencies

Federal Agencies Involved with Immigration Enforcement:

The Department of Homeland Security includes the sub-agency Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). ICE was established in 2003. It is responsible for enforcement of immigration law and removal of individuals in violation of immigration law. It investigates activities relating to the movement of people and goods to and from the country.

The Department of Justice, the legal arm of the government,controls the immigration courts. It has other responsibilities relating to immigration, for example, as described below.

Implementing the “Spending Power” through the Executive:

Congress is the only federal authority that can use the federal government’s spending power (offer of money) to encourage states or local governments to enforce federal policies. However, Congress can give the authority to administer federal grant programs to executive agencies, like the Department of Justice.

Because the Department of Justice administers the Edward Byrne Justice Assistance Grant Program and the State Criminal Alien Assistance Program, it can set rules on how states and local governments can get the funds. It can only determine rules within the boundaries defined by Congress.

In July 2016, the Department of Justice issued “guidance” (a formal letter) relating to the Edward Byrne Justice Assistance Grant Program and the State Criminal Alien Assistance Program. The guidance said that any state or local government participating in these two of its programs related to state and local criminal justice would have to show that they cooperate with the federal government’s immigration enforcement efforts as stated in 8 U.S.C. Section 1373. The Department of Justice had the power to do this because it was granted the authority by Congress.

Sanctuary Cities Executive Order

In January 2017, President Trump wanted to “remind” states that the federal government has the power to give money to state and local governments. President Trump gave an Executive Order on January 25, 2017 threatening to cut federal funding to local governments that refuse to follow 8 U.S.C. Section 1373. Among the jurisdictions that could suffer from this order are those with “sanctuary policies,” cities and counties with policies that local officials should not seek immigration information from people and that refuse to turn over to the federal government people with questionable immigration status.

If a particular federal program was attached through Congressional power (legislation or delegation) to a policy requirement (e.g. that a state or local government getting money must obey a certain law), then the funding threat is valid. If the requirement was not already there, an Executive Order cannot create it. That is why President Trump was sued by Santa Clara and San Francisco. The Executive Order purported to attach all federal grant programs to compliance with Section 1373. See Judicial column, County of Santa Clara v. Trump and City and County of San Francisco v. Trump.

Federal Courts

This section outlines cases relevant to the 10th Amendment and Congress’s Spending Power. The last case listed here ruled on Trump’s executive order attempting to block local governments from getting funding if they do not help enforce immigration law.

Courts Interpreting the 10th Amendment:

In Printz v. United States (1997), the Supreme Court overturned part of a federal law for attempting to require state law enforcement officers to conduct background checks on potential gun purchasers. The background checks would be undertaken on behalf of the federal government because the policy was a federal policy (the Brady Handgun Violence Prevention Act). The court ruled that the 10th Amendment’s “dual sovereignty” principle (federal government does federal law; states do state law) barred the federal government from making states participate by doing the background checks.

In New York v. United States (1992), the Supreme Court overturned part of a federal law that attempted to make states responsible for disposing of certain radioactive waste on behalf of the federal government. The court ruled the 10th Amendment separation between federal and state governing barred the federal government from “commandeering” the states like that.

Courts Interpreting the Spending Power:

In South Dakota v. Dole (1987), the Supreme Court upheld a federal law challenged by South Dakota. The law used a threat of revoking federal funds to get the state to raise its drinking age to 21. South Dakota argued that the law, which threatened to take 5% of the state’s highway funds if it did not comply, was an unconstitutional use of the Spending Power. The Court disagreed, saying the federal government is allowed to induce states into federal programs that “promote the general welfare,” as long as Congress made the requirement clear so that the states are aware of their choice (potential to forfeit federal funds). Further, the court said the 5% potential loss of highway funds is not coercive because it is not significant enough to cross the line into compulsion.

In National Federation of Independent Business v. Sebelius (2013) (the case challenging Obamacare), the Supreme Court ruled against the federal government’s power to use money as an incentive for states to participate in a federal program. In this case, the federal program was Medicaid. Under the Affordable Care Act, the federal government threatened to take away states’ Medicaid funds if the states did not expand the group of people to which they offered Medicaid, to align with the goal of the federal program. Until this point, Medicaid had offered money to whatever degree the states wished to participate, and with the Affordable Care Act the federal government threatened to take that away and make states accept the whole deal (give Medicaid to anyone who qualified under the new federal standard). States, at the time, received a significant portion of their total budget through the Medicaid program (around 10%). The Court ruled that the amount of money involved, in addition to it being money the states already relied on, made the Affordable Care Act requirement to expand Medicaid coercive on states. The Court distinguished South Dakota v. Dole because in that case, the funds constituted only one half of one percent of the state’s budget. In this case, the much larger percentage made the federal pressure cross the line into coercion, which the Spending Power does not allow.

The Spending Power and Immigration Enforcement:

Like in the cases above, the current federal government (under President Trump) is attempting to use Congress’s Spending Power to encourage states and local governments to help enforce federal law. These following two cases were consolidated because they have the same issue, and they are in the same federal district court (Northern District of California).

These two cases were filed in federal court in California (the Northern District of California) by San Francisco and Santa Clara’s local governments. They challenged President Trump’s Sanctuary Cities Executive Order (See Executive column) for violating the 10th Amendment and the Spending Power. The Executive Order threatened to cut federal funding from local governments that do not comply with 8 U.S.C. Section 1373. Section 1373 requires local governments to communicate with federal authorities on immigration enforcement (see Legislative column, left). San Francisco and Santa Clara have policies that they will not transmit information about an individual’s suspected immigration status to federal authorities, in apparent violation of Section 1373. The local governments have the right to do this under the 10th Amendment. In other words, Section 1373 has no teeth unless Congress attaches some funds to it.

On April 25, 2017, the court (Northern District of California) ruled on a preliminary matter: is San Francisco and Santa Clara’s case strong enough to call for a temporary block on the Executive Order? The court said yes.

The court said President Trump’s Executive Order tried to attach all federal funds to compliance with Section 1373. That includes not just the federal funds attached to Section 1373 through Congressional power (or through delegation as mentioned in the Executive column), but even potentially Medicaid and all other funds. The court ruled such a broad attachment of funds would be a violation of the Spending Power and the 10th Amendment. The preliminary ruling is valid until the case goes to trial (or if it gets a decision on appeal).

Update: Trump appealed to the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals and lost. The 9th Circuit agreed with the lower court that the executive order is likely unconstitutional and should continue to be placed on hold (August 2018).

State Governments

In the immigration enforcement battle between the federal government and sanctuary cities or sanctuary counties, the state can be the deciding factor. The 10th Amendment does not allow the federal government to command cities and counties, but the state can command its own localities.

First, see the two main camps of local governments:

Local Government Policies on Immigration Enforcement:

Pro-enforcement (non-sanctuary cities)

Local governments that want to help enforce federal immigration law can participate through a type of agreement with the federal government authorized by the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act of 1996, provision 287(g). 287(g) Agreements give local officials the power to inquire about federal immigration offenses and to make related arrests. Another type of program called Secure Communities (a Department of Homeland Security program, not a Congressional program) works to share information between local jails and the federal government. Local governments can submit fingerprints of any arrestees to Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) so the federal agency can check for potential immigration violations. If they want, the localities can hold individuals suspected of immigration violations for federal authorities.

Against-enforcement (sanctuary cities or sanctuary counties)

Alternatively, a local government can choose not to help the federal government enforce immigration law (unless there is a state law against it, see below). These local governments are called “Sanctuary Cities” and “Sanctuary Counties.” In these localities, the government agents (police and other public safety officials, for example) will not ask about immigration status when going about their activities. In other words, the cities/counties will not spend local funds to help the federal government enforce federal immigration law. Local governments with these policies cannot actively subvert federal enforcement efforts, but the federal government cannot command the states to perform federal responsibilities.

State Laws on Immigration Enforcement:

States can determine what their local governments are allowed to do. Some states have made it clear that they are on the federal enforcement team and that all their local governments must follow.

For example, in May 2017, Texas passed a law requiring local police and other local government officials to help enforce federal immigration law. The law will probably face legal challenge from civil rights groups, who already claim it may cause 4th Amendment problems (causing unconstitutional stops and searches of individuals suspected of immigration violations).