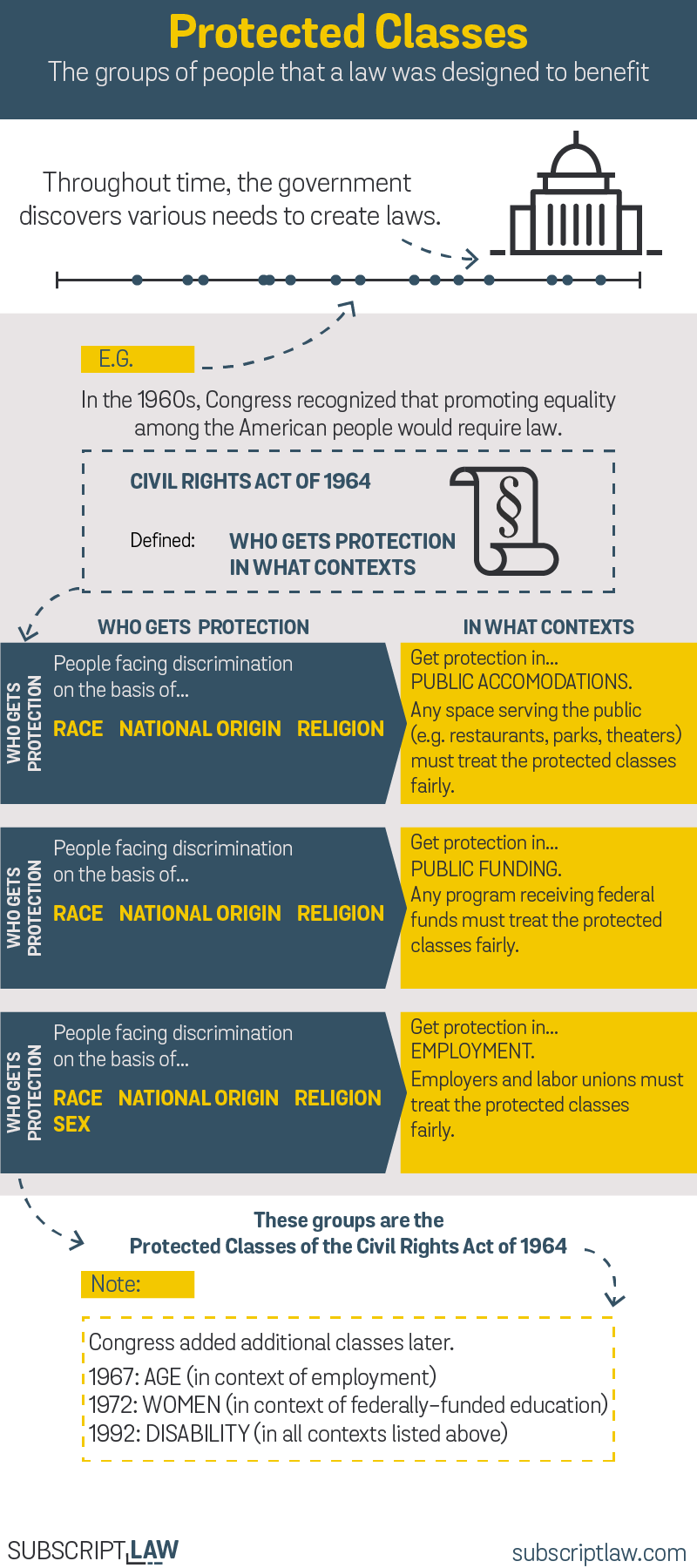

Discrimination: which groups get federal protection?

Not all unfair treatment is a violation of the law. In the employment context, for example, courts have noted they are not “super-personnel” departments meant to second guess every employment decision (see, e.g., Johnson v. Weld County (10th Cir. 2010); Chapman v. AI Transp. (11th Cir. 2000). Instead, the civil right statutes only prohibit actions that occur because of a person’s membership in a protected class. Congress has extended protections to specific groups who have historically faced hardships in obtaining employment, housing, and other public accommodations.

What are the protected classes?

Under federal law, employers cannot discriminate on the basis of race, color, national origin, religion, sex, age, or disability. The law is not, however, a blanket bar on employers taking into account a person’s membership in one of these groups in all circumstances. For example, employers may consider membership in a protected class when making employment decisions if there is a business necessity for doing so, or if membership in a protected class is a bona fide occupational qualification. There are also certain criteria that must be met in order to be considered a member of protected class, such as being a qualified individual with a disability to be entitled to reasonable accommodations in the workplace.

History of the protected class

Race and color were the earliest protected classes. The Civil Rights Act of 1866 prohibits discrimination “in civil rights or immunities . . .on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.” Section 1981(a) of the Act barred discrimination in the making of contracts on the basis of race and color, which is understood to include employment contracts.

The protected classes grew significantly in the 20th Century, beginning with the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Title VII of the Act prohibits discrimination in employment on the basis of race, color, national origin, sex, and religion. The Act also created the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (“EEOC”), the independent federal agency that oversees the enforcement of Title VII and the other civil rights acts as they apply to employment.

In 1967, Congress added age to the listed of protected classes with the Age Discrimination in Employment Act (“ADEA”). The ADEA only applies to individuals age 40 and older, and the federal courts have interpreted it narrowly over time, generally requiring more than a year or two age difference between employees to support a finding of age discrimination.

Disability first entered the list of protected classes in a limited way in 1973. The Rehabilitation Act of 1973 prohibits discrimination based on disability in federal employment. Employees in the private sector gained similar protections in 1990 with the passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act (“ADA”). Congress expanded the definition of who is covered by the ADA in 2008 with the Americans with Disabilities Amendments Act.

Protections against harassment

Title VII states that an employer may not discriminate against an employee or applicant for employment “because of” the person’s race, color, national origin, sex, or religion. The statute does not specifically reference harassment, or the creation of a hostile work environment that may include non-economic harms such as name calling or inappropriate touching. In Meritor Savings Bank (1986), the Supreme Court recognized that such harassment, although it might not rise to the level of distinct economic harms such as a demotion or firing, is covered by Title VII. This interpretation also encompasses the other civil rights statutes, and includes harassment based on retaliation.

The Supreme Court limited the reach of Title VII’s harassment protections in Meritor Savings to only those instances where the harassment is so “severe or pervasive” that it alters the terms and conditions of the employment. Since then, courts across the country have had to determine on a case-by-case basis what harassment is sufficiently severe or pervasive to meet this standard. Generally there must be multiple incidents of harassment to meet the standard. In only very limited circumstances, such as the use of specific racial slurs or the hanging of a noose, is a single incident sufficiently severe.

The ongoing evolution of sex as a protected class

In Price Waterhouse v. Hopkins (1989), the Supreme Court held that sex stereotyping is a form of prohibited sex discrimination. In Hopkins, Price Waterhouse denied Ms. Hopkins a position as a partner. The partnership committee based its decision on Ms. Hopkins not behaving as they expected a woman to in the workplace. For example, Ms. Hopkins received feedback that she should “walk more femininely, talk more femininely, dress more femininely, wear make-up, have her hair styled and wear jewelry.” The Court concluded that allowing such discrimination would undermine the purpose of Title VII.

The concept of sex stereotyping is an important part of more recent developments in the area of protected classes. Two federal courts of appeals and the EEOC have concluded that Title VII prohibits discrimination based on sexual orientation because it is a form of sex discrimination. These courts have concluded that sexual orientation discrimination is based on stereotypes of who an individual should be attracted to based on the individual’s sex. As the EEOC noted in Baldwin v. Department of Transportation (2015), “‘[s]exual orientation’ as a concept cannot be defined or understood without reference to sex.”

The Bostock Supreme Court ruling

In June 2020, the Supreme Court issued a decision in Bostock v. Clayton County, Georgia, holding that Title VII’s prohibition against discrimination “because of . . . sex” encompasses discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity. The Court rested its decision on the plain language of the statute, which bars an employer from treating an employee worse than others because of the employee’s sex, and concluded that any action taken because of sexual orientation or gender identity inherently involves a consideration of an employee’s sex. The Court illustrated this through several examples, including a hypothetical involving a model employee introducing a woman as the employee’s spouse at a company holiday party. The Court explained that whether the employee would fire the employee for violating a policy against employing gay or lesbian employees would turn on the sex of the employee—if the employee is a man, the company will not fire him. If the employee is a woman, the company will terminate her employment.

By relying on the plain language of the statute, the Court did not need to reach the question of whether sexual orientation or gender identity discrimination involves sex stereotyping. It also did not expand Title VII to include new protected classes, as the dissenting justices asserted. Instead, the Court clarified that sexual orientation and gender identity discrimination are forms of sex discrimination

Conclusion

Protected classes are how federal law conceptualizes protections against discrimination. The understanding of the classes may continue to evolve, either incrementally through courts or through federal legislation. Societal responses to new issues of discrimination generally start the process.

Editor’s Note: This report was updated to include a discussion of the June 2020 Bostock Supreme Court ruling. The original report was published December 4, 2018.