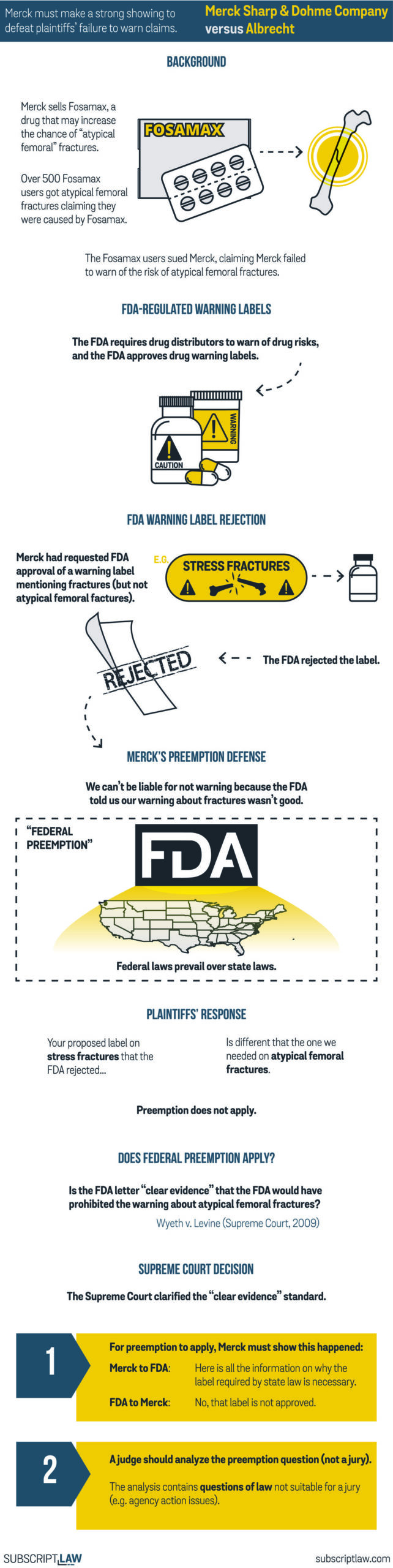

Merck disappoints pharmaceutical industry in the Supreme Court

Argument: January 07, 2019

Decision: May 20, 2019

Petitioner Brief: Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp.

Respondent Brief: Doris Albrecht

Court Below: Third Circuit Court of Appeals

Merck manufactures a drug called Fosamax that treats and prevents osteoporosis. In addition, however, Fosamax increases a user’s chance of getting a certain type of bone fracture — an atypical femoral fracture.

The connection wasn’t proven at the time Merck originally got FDA approval, so the original drug warning label didn’t mention it. The evidence had become more clear by 2008, and Merck applied to the FDA to add a couple of notes about fractures to the Fosamax warning label. The FDA approved one of them, which mentioned a “low energy femoral shaft fracture” and rejected another one, which was a longer discussion of stress fractures. The FDA decided the discussion of stress fractures didn’t match the fractures established in the literature. The FDA invited Merck to reapply with an edited version, but Merck did not. Within the next few years, Merck and the FDA communicated about the potential for new warnings relating to atypical femoral fractures, and the FDA finally — on its own initiative — required Merck to provide notice of that specific fracture in 2011.

The lawsuit

In 2010, Merck got sued. Over 500 Fosamax users had developed atypical femoral fractures. The plaintiffs claimed Merck’s failure to mention atypical femoral fractures on the Fosamax warning label violated state laws. Merck said, actually, we tried to add a warning back in 2008 and the FDA rejected it. The FDA wouldn’t have allowed the label you are seeking (the label you claim state law requires).

Federal preemption

It is true that if the FDA has officially rejected a drug manufacturer’s attempt to include a warning, then — even if state law requires it — the manufacturer cannot be held liable. That’s because the Constitution says federal law “preempts” state law. To put it in the context of this case, official FDA labeling restrictions prevail over state law failure-to-warn claims.

But was the FDA rejection of Merck’s warning on stress fractures the official word that the FDA would not have approved the label on atypical femoral fractures that plaintiffs say was required?

The Supreme Court was asked to decide how a court should evaluate whether the FDA has, in effect, disapproved of a drug warning label required by state law.

Supreme Court precedent: Wyeth v. Levine

In 2009, the Supreme Court resolved a similar case on federal preemption: Wyeth v. Levine. In Wyeth, a drug user developed gangrene after having received an injection of Phenergan, an anti-nausea drug. The plaintiff argued the drug manufacturer, Wyeth, should have issued a warning addressing the risk of gangrene when the drug is administered through an injection (as opposed to through an IV drip).

The Court rejected Wyeth’s FDA preemption argument for two reasons: Wyeth had not supplied the FDA any information about the difference between the IV drip versus injection method when it sought approval of the warning label. And the FDA had not made an affirmative decision to preserve the existing warning label.

Federal law establishing FDA control over drug labeling, the Court explained, was not meant to limit states’ abilities to protect consumers. FDA warning label regulation does not come with a complete guarantee that all warnings are covered. In fact, federal law puts the obligation on the drug manufacturer to make sure its warning labels are adequate. The FDA obligates drug manufacturers to apply for changes to drug warning labels based on new evidence.

Thus, the Wyeth Court ruled, “absent clear evidence that the FDA would not have approved a change to Phenergan’s label, we will not conclude that it was impossible for Wyeth to comply with both federal and state requirements.”

Ruling on “impossibility preemption”

Wyeth’s facts were different than in the Merck case. In Merck, there actually had been some communication between the FDA and Merck about fractures. The Supreme Court in this case, then, was asked to clarify the ruling in Wyeth so that courts can evaluate “impossibility preemption” more widely.

Drug manufacturers were hopeful that the new conservative-leaning Court would relax Wyeth’s strong preemption standard. But it didn’t. Both Gorsuch and Thomas joined the opinion written by Breyer (along with the more expected Ginsburg, Kagan and Sotomayor).

From Breyer’s opinion:

[S]howing that federal law prohibited the drug manufacturer from adding a warning that would satisfy state law requires the drug manufacturer to show that it fully informed the FDA of the justifications for the warning required by state law and that the FDA, in turn, informed the drug manufacturer that the FDA would not approve changing the drug’s label to include that warning.

The opinion emphasized a strict interpretation of when the FDA would be considered to overrule state failure to warn claims. The FDA must have specifically and fully addressed the literature and warning label that the state law requires (i.e. the label that plaintiffs argue the state requires).

The Supreme Court did not decide the merits. It sent the case back to the lower court to conduct the analysis.

Ruling on who decides: judge versus jury

The Supreme Court made an additional ruling to control the lower court’s evaluation. The parties had asked whether the analysis of the impossibility (preemption) question would be a question for the jury or for the judge. Generally, a jury decides questions of facts, and judges decide questions of law.

The Court determined that questions of agency action that must be resolved in this type of case are questions of law. FDA action can only supersede state law if it’s Congressionally mandated FDA action (comes from federal law). So a judge must decide whether the FDA actions at issue are Congressionally mandated and should be afforded supremacy. The Court listed examples of the types of FDA action that would count: “by means of notice-and-comment rulemaking[;] by formally rejecting a warning label[;] or with other agency action carrying the force of law.”

Concurrences

Justice Thomas concurred in the majority opinion but also wrote separately to emphasize that Merck was not able to point to any real federal law that would have prevented it from including a warning notice about atypical femoral fractures. He notes the 2009 rejection by the FDA

neither marked “the consummation of the agency’s decisionmaking process” nor determined Merck’s “rights or obligations.” . . . Therefore, the letter was not a final agency action with the force of law, so it cannot be “Law” with pre-emptive effect.

Alito wrote the less agreeable concurring opinion on which Roberts and Kavanaugh signed. They agreed only that the preemption issue should be decided by a judge, not a jury. But they did not agree with the picture of the facts that the majority presented. For example, Alito explained that the majority failed to acknowledge some additional communication between the FDA and Merck that might have painted a different scene. Alito also said the majority’s recounting of the history of FDA regulation and the role and meaning of FDA notices and discussion regarding warning label applications was inaccurate and may lead to inappropriate preemption results.