McKinney seeks a jury to determine if he can avoid the death penalty

In the United States Supreme Court

| Argument | December 11, 2019 |

| Decision | February 25, 2020 |

| Petitioner Brief | James Erin McKinney |

| Respondent Brief | Arizona |

| Opinion Below |  Supreme Court of the State of Arizona |

Case Decision

On February 25, 2020, the Supreme Court ruled against James McKinney.

Scroll down for our Decision Analysis

December 10, 2019

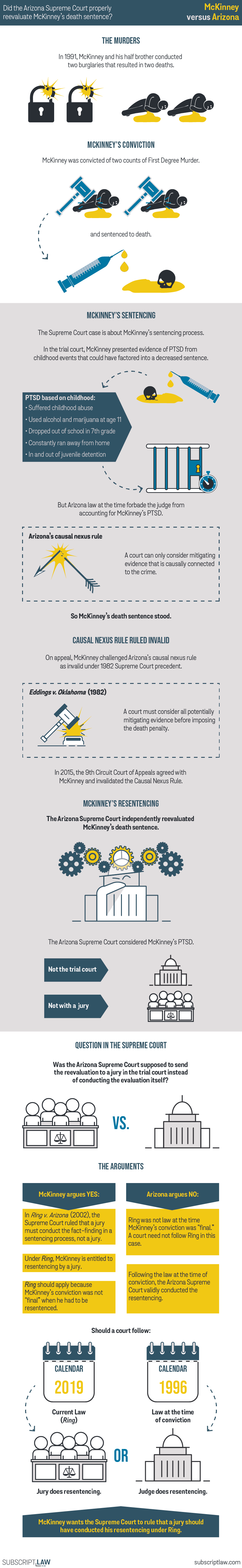

In 1991, at the age of 23, James McKinney and his half-brother Michael Hedlund committed two burglaries that resulted in two deaths. The state of Arizona tried McKinney and Hedlund before separate juries. Hedlund’s jury found him guilty of one count of first-degree murder and one count of second-degree murder. McKinney’s jury found him guilty of two counts of first-degree murder. McKinney’s jury, however, did not specify whether it reached the verdict by finding premeditation or by finding felony murder.

Premeditation vs. Felony Murder

Premeditation requires the homicide to be willful and deliberate. With felony murder, the homicide only needs to occur in the commission of a prescribed felony—such as, arson, rape, robbery, or burglary. Premeditation reflects the basic principle that the punishment for homicide must be measured by the culpability of a guilty mental state. Felony murder does not consider the offender’s mental state.

Mitigating evidence

McKinney had a horrific childhood due to poverty, physical abuse, and emotional abuse. At 11 years-old, McKinney began drinking alcohol and smoking marijuana. Having dropped out of school in the seventh grade, McKinney repeatedly tried to run away from home and was placed in juvenile detention.

A neuropsychologist diagnosed McKinney with PTSD “resulting from the horrific childhood McKinney had suffered.” At trial, the neuropsychologist further testified that witnessing violence potentially triggered McKinney’s childhood trauma and produced “diminished capacity.” This evidence is legally referred to as “non-statutory mitigating evidence.” While not negating the wrongful action, non-statutory mitigating evidence tends to show that the accused may have had some grounds for acting the way he did. Here, for example, McKinney had PTSD. Despite being the burglar, the inherent violence of the burglary potentially triggered an episode in McKinney, producing McKinney’s “diminished capacity.” The trial judge found the neuropsychologist’s testimony credible.

Sentenced to death by trial judge

Only the judge heard the non-statutory mitigating evidence. There was no jury present. At the time, Arizona law prohibited judges from considering non-statutory mitigating evidence, which is unconnected to the crime. Despite crediting the neuropsychologist’s testimony, the judge concluded McKinney’s PTSD was not connected to the burglaries, which disabled the judge from considering it as non-statutory mitigating evidence at sentencing. The judge, without any input from a jury, sentenced McKinney to death.

Cycle of appeals

In Arizona, death penalty cases are granted an automatic direct appeal to the Arizona Supreme Court, the highest court in the state. Arizona’s highest court affirmed McKinney’s death sentence. A petitioner who wishes to appeal the highest state court proceeds to the federal court system. In 2003, McKinney filed a habeas petition in federal court. A habeas petition is an application brought by a prisoner before a court to determine if the person’s imprisonment is lawful. The federal district court denied relief. McKinney appealed to the federal Court of Appeals in the Ninth Circuit. A three-judge panel also denied relief. McKinney appealed again for an en banc hearing before the entire Ninth Circuit bench.

Ninth Circuit: Arizona must consider McKinney’s PTSD

McKinney’s appeal before the Ninth Circuit addressed whether Arizona violated the Constitution by not considering McKinney’s PTSD. The Ninth Circuit held that Arizona’s refusal to consider McKinney’s PTSD violated the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in Eddings v. Oklahoma, 455 U.S. 104 (1982). In Eddings, the Court held that when sentencing in a death penalty case, neither a judge nor a jury may refuse to consider any relevant mitigating evidence. Due to Arizona’s violation of Eddings, McKinney was entitled to a resentencing. The Ninth Circuit remanded to the federal district court to either correct the constitutional error or vacate the sentence and impose a lesser sentence.

Arizona appellate court independently reviews the sentence

Before the federal district court acted, Arizona asked the Arizona Supreme Court to independently review McKinney’s sentence. By independently reviewing McKinney’s sentence, the Arizona Supreme Court treated the trial court’s credibility determinations and findings of fact as binding, but examined whether those facts and procedures satisfied the rule of law.

The Arizona Supreme Court directly reviewed McKinney’s sentence, without a jury. The Arizona Supreme Court afforded the non-statutory mitigating evidence minimal weight, determining the PTSD diagnosis was not “sufficiently substantial” to warrant a lesser sentence, and affirmed the death penalty.

McKinney argues that it was not the appellate court’s place to consider and evaluate the mitigating evidence and resentence. The evidence must be presented to a jury, who will then decide whether to sentence McKinney to death.

Current law: resentencing must be by a jury, not a judge

McKinney opposed Arizona’s motion before the Arizona Supreme Court arguing that he was entitled to resentencing by a jury, not a judge, under the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in Ring v. Arizona, 536 U.S. 584 (2002). In Ring, the Court held that only juries, not judges, must make the findings necessary to impose the death penalty. The Arizona Supreme Court disagreed, finding that McKinney was not entitled to resentencing by a jury because his case was “final” before the U.S. Supreme Court issued its decision in Ring. Here, the law at the time of McKinney’s original sentencing, in 1996, did not require a jury to make the determination. And the case was “final.” Therefore, the Arizona Supreme Court held that the resentencing process should follow the law in 1996, not the law after 2002, when Ring was decided..

Was the case “final”?

According to Arizona, a case is considered “final” when all appeals are exhausted, making the result irreversible. McKinney argues otherwise.

McKinney relies on Jimenez v. Quarterman, 555 U.S. 113, 120 (2009) to argue the case is non-final. The Supreme Court held in Jimenez that a defendant’s “final” conviction becomes “again capable of modification through direct appeal to the state courts and to this Court on certiorari” through direct review. Thus, McKinney’s resentencing process should follow current law; not old law.

McKinney: only trial court may resentence

McKinney appealed his death sentence to the U.S. Supreme Court raising two issues. First, whether only a trial court may conduct proceedings resulting from constitutional errors under Eddings. McKinney argues that an Eddings error must be remedied by resentencing in the trial court. In Mills v. Maryland, 486 U.S. 367 (1988), the Court stated where the “sentencer’s failure to consider all of the mitigating evidence risks erroneous imposition of the death sentence,” it is the Court’s “duty to remand [the] case for resentencing.” Here, the Ninth Circuit remanded the case to the district court for either resentencing or imposing a lesser sentence. To avoid the potential reduction of McKinney’s death sentence by the federal district court, the state of Arizona asked the Arizona Supreme Court, which is neither the sentencing authority nor a trial court, to independently review McKinney’s sentence.

Citing Arizona law, McKinney objected because the Eddings error may only be remedied by a trial court. In State v. Bible, 858 P.2d 1152, 1211 (Ariz. 1993), the Arizona Supreme Court described Arizona’s sentencing scheme, stating that the “sentencing authority in all criminal cases, and especially capital cases,” is placed “with the trial judge.” And in State v. Rumsey, 665 P.2d 48, 55 (Ariz. 1983), the Arizona Supreme Court described its role as “strictly that of an appellate court, not a trial court.” Any independent review of capital cases is conducted “as an appellate court, not as a trial court.”

Which law applies?

On appeal, McKinney also raises a second issue: whether consideration of the mitigating evidence and imposition of the death penalty at sentencing requires a determination by a jury, not a judge.

Arizona argues McKinney’s case was final nearly six years before Ring was decided in 2002. Therefore, only the law at the time, in 1996, applies—precluding McKinney from having a jury consider the mitigating evidence and sentence accordingly.

Must courts apply “current law” when a matter is remanded for error correction? The current law requires a jury, not a judge, to review mitigating evidence and decide whether to impose the death penalty. Here, Arizona violated Eddings by not considering McKinney’s non-statutory mitigating evidence. The Ninth Circuit deemed the Arizona law unconstitutional. McKinney’s case was remanded for resentencing. Does that render McKinney’s case non-final, where the result of the resentencing can be appealed? If yes, current law would apply. If no, the law at the time, in 1996, applies. That’s a question the Court will decide.

The role of jurors

Since its decision in 2000 in Apprendi v. New Jersey, the Court consistently enhanced the role of jurors in criminal trials. In Apprendi, the Court ruled that, under the Sixth Amendment right to a jury trial, any fact which increases the severity of the sentence must be found by a jury, not a judge. In Apprendi, Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg wrote: “The right to trial by jury guaranteed by the Sixth Amendment would be senselessly diminished if it encompassed the factfinding necessary to increase a defendant’s sentence by two years, but not the factfinding necessary to put him to death.”

The Court’s 2002 decision in Ring made clear that only jurors can decide whether to impose a death sentence and that the jury’s decision cannot be second-guessed by the judge. Again, in 2016, the Court stated in Hurst v. Florida, 136 S. Ct. 616, 619 (2016) the “Sixth Amendment requires a jury, not a judge, to find each fact necessary to impose a sentence of death.”

The U.S. Supreme Court will continue to explore the role of the jury in criminal trials and sentencing, especially when imposing the death penalty. The Justices will hear arguments on December 11, 2019.

DECISION ANALYSIS

Mariam Morshedi

On February 25, 2020, the Supreme Court ruled against James McKinney, a death row inmate who sought to have his sentence reduced based on a review of mitigating evidence. McKinney’s original sentencing did not account for his PTSD, and the federal courts ruled he deserved to have the PTSD factored in.

The Supreme Court case asked whether McKinney’s corrected review of mitigating evidence should have been done by a jury in the trial court or by the Arizona Supreme Court.

The case fell on whether a 2002 Supreme Court ruling should apply. Ring v. Arizona established that a sentencing re-evaluation should be done by a jury in the trial court, and McKinney wanted that precedent to apply to his case.

In a 5-4 ruling (ideological split), the conservative justices ruled Ring does not apply to McKinney’s case because McKinney’s case was final back in 1996 after McKinney’s direct appeal to the Arizona Supreme Court. The majority held that McKinney’s corrected review of mitigating evidence did not disturb the case’s finality. The corrected review, the Court said, was based on federal court collateral proceedings, and is properly classified as a “collateral review.” Ring does not apply retroactively in collateral review proceedings, the Court ruled.

Ginsburg wrote for the dissent and argued Ring should apply because the corrected review of mitigating evidence was actually a “direct review.” It was a re-do of the original direct review appeal to the Arizona Supreme Court, and she argued it should thus be considered a direct review.

Without the application of Ring, the majority applied 1990 Supreme Court precedent, Clemons v. Mississippi. Clemons said an appellate court can reweigh aggravating and mitigating evidence and there is no constitutional demand for a jury in the trial court to conduct the reweighing.