Commentary published in Georgia’s official legislative code is not eligible for copyright protection.

In the United States Supreme Court

| Argument | December 2, 2019 |

| Decision | April 27, 2020 |

| Petitioner Brief | Georgia |

| Respondent Brief | PublicResource.Org |

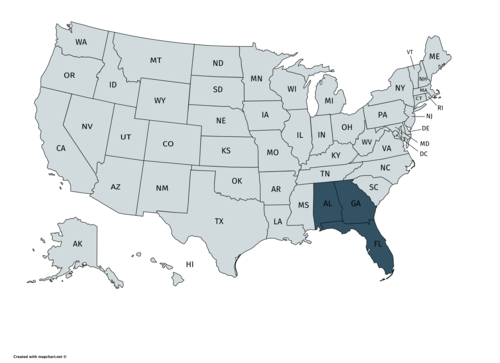

| Court Below |  Eleventh Circuit Court of Appeals |

Case Decision

On April 27, 2020, the Supreme Court ruled against the State of Georgia, holding that commentary published in Georgia’s “official” legal code is not eligible for copyright protection.

The parties

Petitioner, the State of Georgia, contracts with a private company to publish “official” copies of its laws. The publisher also prepares an “annotated” version of Georgia’s laws called the Official Code of Georgia Annotated (OCGA). The annotations include commentary such as summaries of relevant judicial opinions, summaries of relevant opinions of the state attorney general, relevant law review articles and other reference materials. The publisher does not charge the State of Georgia for preparing the annotations and relies on sales of the OCGA for compensation.

Respondent, Public.Resource.Org, Inc. (PRO) is a public interest organization that promotes access to government records and primary legal materials. It publishes online official codes, rules, regulations, and standards adopted by federal, state, and local authorities. PRO also scanned and published the OCGA, including the statutory text and annotations.

Georgia alleged the state holds a copyright in the annotations and sued PRO for publishing the annotations without permission from the state.

Procedural history

The district court entered an injunction against PRO, prohibiting it from posting the OCGA online. The Eleventh Circuit reversed, holding that the annotations in the OCGA are not copyrightable. Both parties agree that, under the “government edicts doctrine,” no one can copyright “the law.” The parties disagree, however, on the scope of the government edicts doctrine.

The issue – scope of the government edicts doctrine

Federal Copyright Law grants protection for “original works of authorship.” 17 U.S.C. §102(a). The Supreme Court has recognized an exception to copyright protection for certain government-produced works. This exception, known as the “government edicts doctrine,” was established in a trio of nineteenth-century cases.

In the first case, Wheaton v. Peters, 33 U.S. 591 (1834), the Court held judges do not hold a copyright in their judicial opinions and cannot convey exclusive rights to publish their opinions. In the second case, Banks v. Manchester, 128 U.S. 244 (1888) the Court clarified that even that non-binding, explanatory legal materials prepared by judges are not copyrightable. Any work prepared by judges acting in their judicial capacity is “authentic exposition and interpretation of the law, which . . . is free for publication to all.” In the third case, Callaghan v. Myers, 128 U.S. 617 (1888), the Court limited the government edicts doctrine outlined in Wheaton and Banks. The Court held an official court reporter is an author that has no authority to speak with the force of law. Therefore, a copyright subsists in explanatory materials prepared by the reporter.

Georgia’s view

Georgia argues the government edicts doctrine only applies to legal texts having legal force. Georgia does not claim a copyright in the OCGA’s statutory text and numbering. However, the annotations published alongside the statutory text are eligible for copyright protection. The annotations do not have the force of law – they are not enacted through bicameralism and presentment. Therefore, they are outside the scope of the government edicts doctrine.

Additionally, states need copyright protection to induce private publishers to prepare and publish annotated codes at negligible taxpayer expense. If copyright protection is not available to protect the annotations, it will be harder, not easier, for citizens to access legal research tools, such as the OCGA and its annotations.

PRO’s view

PRO argues that even works that do not have legal force are within the scope of the government edicts doctrine if the work is held out as a “government edict.” Georgia holds out the OCGA as being published under the State’s authority. The annotations included in the OCGA are routinely cited by Georgia courts as authentic sources of legal meaning. The legislative commission that supervises creation of the annotations does so while operating under legislative authority. Therefore, the OCGA, along with its annotations and statutory text, bears the imprimatur of state authority and falls within the scope of the government edicts doctrine.

The Court’s holding

Justice Roberts, writing for a majority of the Court, held the government edicts doctrine is grounded in construction of the term “author” in the Copyright statute. Officials responsible for creating the law are not considered the “authors” of “whatever work they perform in their capacity” as lawmakers. Just as judges are not the “authors” of their opinions and associated explanatory materials, legislators are also not “authors” of the law they promulgate or the commentary they prepare of those laws.

Copyright eligibility is determined by who created the material and whether it was created in the course of that person’s official duties. The doctrine does not distinguish between different categories of content. For example, a dissenting opinion is not copyrightable, even though it does not have the force of law. Likewise, there is no copyright protection for non-binding legislative materials produced by a legislative body acting in its legislative capacity. There is no copyright for floor statements, proposed bills, committee reports or any other commentary on laws prepared by a legislature.

Accordingly, a work prepared by a state legislature acting in its official capacity does not have an “author” entitled to assert copyright protection. Because Georgia’s annotations are authored by an arm of the legislature carrying out its legislative duties, the government edicts doctrine applies. Although the annotations are not enacted into law through bicameralism and presentment, they are prepared under legislative authority and provide resources the legislature considers relevant to understanding its laws.

Georgia argues it now will not be able to induce private publishers to produce affordable annotated codes. That policy concern is something for Congress to consider, not the courts.

Dissent no. 1: Justices Thomas, Alito and Breyer (in part)

The trio of 19th-century decisions do not provide a detailed explanation of the basis for the government edicts doctrine. The conduct of 22 States, 2 Territories, and the District of Columbia who all rely on arrangements like Georgia’s to produce annotated codes indicates there may be a different (and narrower) understanding of the doctrine. And there may be other reasons why the trio of nineteenth-century cases held judicial opinions and commentary are not eligible for copyright.

Firstly, judicial opinions may not be eligible for copyright because they have binding legal effect, and they are produced and issued at public expense. Furthermore, even not binding judicial commentary enhances the understanding of the “law.” A reader of a judicial opinion will gain insight into the reasoning of the majority’s holding by reading all opinions – including dissents and concurrences.

Unlike judicial opinions and statutes, the Georgia annotations are not law. The annotations explain how others, not the lawmakers, understand a law. Although the annotations are “merged” into an “official” legal code, the same Georgia provision mandating the merger expressly provides that “historical citations, title and chapter analyses, and notes set out in this Code are given for the purpose of convenient reference and do not constitute part of the law.”

Secondly, an author, in the context of copyright law, may be one motivated by the grant of exclusive rights. Judges, when acting in their official capacity, do not fit that description. In this case, Georgia needs copyright protection produce the OCGA and recoup its cost of producing the annotations.

For these reasons, maybe the government edicts doctrine is a limited exception to copyright that only applies to works that have the force of law and are produced by those not motivated by copyright protection. Such a narrow understanding of the government edicts doctrine would allow the Georgia annotations to be protected by a copyright.

Dissent no. 2: Justices Ginsburg and Breyer

There is a difference between commentary created by judges and the annotations created by legislators. Judges are charged with interpreting and applying the law. On the other hand, the role of the legislature is to make laws and to not interpret the law after their enactment. The Georgia annotations, are not part of the Georgia Legislature’s lawmaking process. Firstly, the annotations explain previously enacted statutes. This distinguishes the annotations from other legislative materials such as committee reports, which are related to enactment of a law. The placement of annotations in the OCGA for convenience does not alter their auxiliary, non-legislative character. Accordingly, the Georgia annotations are copyrightable, despite being published by the state legislature while acting in its official capacity.

A practical takeaway is that authorship is critical when determining whether a work produced by lawmaking official or institution is copyrightable. Any work produced by a lawmaking official or institution acting in an official capacity is not copyrightable – regardless of the specific content. However, the government edicts doctrine does not apply to non-lawmaking officials. Therefore, states may assert copyright protection in works created by their non-lawmaking institutions such as universities, libraries, and tourism offices.