The legal battle over DACA: A Preview

In the United States Supreme Court

| Argument | November 12, 2019 |

| Decision | June 18, 2020 |

| Petitioner Brief | DHS, et al. |

| Respondent Briefs | California, et al., Regents, et al., D.C., New York, et al., DACA Recipients, et al. |

| Courts Below |  Ninth Circuit, Second Circuit and D.C. District Court |

Case Decision

On June 18, 2020, the Supreme Court ruled against DHS. The government’s termination of DACA was “arbitrary and capricious” in violation of the Administrative Procedure Act.

Scroll down for our Decision Analysis.

This week the Supreme Court will be hearing oral arguments on legal issues related to a highly controversial action by the Trump administration. The federal government declared it will cut the federal DACA program which provides temporary protections to qualified childhood arrivals currently without immigration authorization. Three lawsuits challenging the decision to terminate DACA have reached the Supreme Court, and the Justices will address the legal issues together.

What is Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals?

Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (“DACA”) is a program that permits undocumented people to apply for work authorization and protection from deportation in two-year increments. The Obama administration’s Department of Homeland Security (“DHS”) Secretary Janet Napolitano first announced the decision to exercise discretion over childhood arrivals’ cases in 2012 and stressed the need for a permanent pathway to lawful status for the population commonly referred to as “Dreamers”.

To be considered for this temporary protection, applicants had to prove that they entered the U.S. before their 16th birthday, that they had resided in the U.S. since June 2007, and that they were either enrolled in/ graduated from school or had military service. Additionally, DHS requires each applicant to submit to a background check and automatically disqualifies anyone who has sustained even a single “significant misdemeanor” (e.g. DUI).

Why does DACA matter?

Aside from the direct benefits of work authorization and protection from immigration enforcement, approximately 800,000 DACA beneficiaries have unlocked opportunities previously unavailable to them. Studies into DACA’s impact consistently find that recipients experience improvements in access to education, employment, healthcare, housing, and in their perceptions of safety. These improvements extend to their families, employers, and surrounding communities.

According to opponents of DACA, the program sends the wrong message to people around the world seeking to enter the country. In other words, the program encourages illegal immigration by giving people who entered “illegally” a path to citizenship.

Termination of DACA

Leading up to the 2016 presidential elections, then-candidate Donald Trump campaigned on anti-immigrant rhetoric. Trump repeatedly promised to rescind DACA protections. On September 5, 2017, Trump appointee Attorney General Jeff Sessions announced the administration was rescinding DACA, characterizing it as “executive amnesty” and a “violation of law” and directing Congress to address the benefit through legislation within six months. Congress did not act, and Trump followed the announcement with a tweet that he would “revisit the issue” if Congress failed to “legalize DACA”. DHS announced that it would not consider any DACA applications filed after October 5, 2017, leaving hundreds of thousands of people’s futures uncertain.

The legal challenges

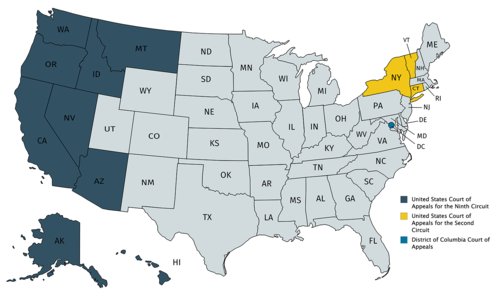

Three lawsuits followed the rescission of the DACA program in California, the District of Columbia, and New York. These cases are now consolidated before the Supreme Court as Department of Homeland Security v. Regents of the University of California. All three cases argued that the sudden rescission of DACA violated the Administrative Procedure Act, as well as the rights of DACA recipients. All three cases resulting in holdings restoring DACA for those who had already applied.

The Supreme Court will hear oral arguments on two core issues: (1) whether the administration’s decision to terminate DACA is judicially reviewable; and (2) whether the decision to terminate DACA was lawful.

The arguments

Department of Homeland Security’s position is that the creation of DACA was purely a decision of “nonenforcement” of existing law. That is, DHS contends that existing law finds that persons in the United States without authorization are otherwise deportable and ineligible for work authorization. DHS’s decision to rescind its nonenforcement policy, then, is an enforcement decision of the sort traditionally “committed to an agency’s absolute discretion.” As such, no explanation is owed to the public.

The challengers argue that the termination of DACA is reviewable because DHS claimed it was compelled to terminate DACA as a matter of law. In claiming that DHS’s decision was required as a matter of law, it shifted responsibility to the courts to decide what the law is. Additionally, the Administrative Procedure Act requires a certain level of transparency so that decisions can be reviewed for abuse of discretion. The Trump administration detailed conflicting reasons, some of which were disclosed after terminating DACA or not disclosed at all. After all, how could Trump tweet he would “revisit” DACA if Congress failed to enshrine protections in a permanent law if the administration truly believed DACA was unlawful?

The challengers also argue that the high stakes for the individuals impacted by the DACA program, decisions to terminate the program should be reviewed to ensure the agency action is not “arbitrary and capricious”. In other words, the reasoning must pass a court’s review to ensure it was not random and impulsive.

The Justices will hear arguments on November 12, 2019.

Correction: A previous version of this article misstated the description of the DACA program in the introduction. Subscript Law editors are responsible for the error and not Contributor Kristina McKibben.

DECISION ANALYSIS:

June 19, 2020

The Supreme Court ruled against the “arbitrary and capricious” way the Trump administration terminated Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (“DACA”). The temporary protection of nearly 700,000 undocumented youth from immigration enforcement remains in place for now.

Background

DACA refers to an Obama-era decision to deprioritize certain childhood arrivals for deportation. To qualify, applicants would submit to screening by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (“DHS”) to receive temporary protection from deportation and a work permit. DACA did not provide a pathway to permanent status, but did serve as a nexus to identification, healthcare access, limited financial aid for education, and other important aspects of life otherwise unavailable to undocumented people. On September 5, 2017, the Trump administration announced its decision to terminate DACA.

On November 12, 2019, the Supreme Court considered whether federal courts had the authority to review the termination of DACA protections, and, if so, whether the reasoning for terminating DACA violated the Administrative Procedures Act (“APA”).

The majority opinion

Chief Justice Roberts wrote the 5-4 decision holding first that the Trump administration’s decision to terminate DACA is reviewable by federal courts. Next, the Court concluded that DHS acted outside of procedural boundaries when it decided to terminate the program.

The DACA termination is reviewable

Regarding whether the DHS decision to terminate DACA is reviewable by courts, the Court ruled against the government. The government argued that the DHS decision falls within a type of executive action which is “committed to agency discretion by law,” meaning courts cannot review it.

The Court rejected the argument by distinguishing other cases of agency action falling within that category. For example, the Court said that the termination of DACA is not like when a criminal prosecutor takes an action of non-enforcement. Although it’s true that DACA is a policy of non-enforcement, the Court ruled that DACA is much more: DACA created an adjudicatory process for identifying people who would qualify for immigration non-enforcement. Further, it created rights for beneficiaries of the program (the right to request work authorization and eligibility for Social Security and Medicare). “[A]ccess to these types of benefits is an interest ‘courts are often called upon to protect,’” the Court said in determining that courts could review the government’s decision to terminate DACA.

The DACA termination violated the law

The Court ruled that the Trump administration violated procedural rules when it terminated DACA. For one, the government failed to “defend its actions based on the reasons it gave when it acted.” The government gave several different reasons for terminating DACA at different times. In an early DHS memo addressing the termination of DACA, the DHS Secretary states that DACA is legally defective. In a second memo issued nine months later, the subsequent DHS Secretary appears to balance reliance interests of DACA recipients with immigration deterrence policies. This, the Court says, violates a “foundational principle of administrative law” that bars “post hoc rationalizations.”

Further, the Court said, the government acted arbitrarily and capriciously in violation of the Administrative Procedure Act. The Court reasoned that the DHS Secretary did not conduct a proper analysis of the entire DACA program because she relied on a conclusion by the Attorney General that only part of the program is legally defective. The Attorney General concluded that the decision to grant benefits and work authorization to program beneficiaries violates immigration law, but the Attorney General did not conclude any illegality on the other major part of the DACA program: the forbearance of deportation proceedings. Without properly considering a major aspect of the program, the Secretary relied on the Attorney General’s conclusion to terminate the entire program. Based on this neglect, the Court concluded the decision was arbitrary and capricious.

Additionally, the Court ruled that the abrupt decision to terminate DACA did not take into account the hardships of DACA recipients who stood to lose prospects associated with their quasi-legal status: educational opportunities, military service, or fully access medical treatment. Instead, it abruptly ended the program without any evident consideration to alternatives or wind-down periods.

The dissenting opinions

Justice Sotomayor concurred with the majority but dissented in that the Court too hastily dismissed equal protection claims.

Justice Thomas dissented, joined by Justices Alito and Gorsuch, opining that DACA illegally conferred lawful status without Congressional process. (Author’s note: This is incorrect. DACA does not, in fact, confer lawful status, a distinction made clear in the initial DACA announcement memo.)

Justice Kavanaugh issued a dissent, forecasting that DHS could successfully terminate DACA by simply elaborating on the later memo policy considerations while on remand to the lower court.

The impact

Nearly 700,000 undocumented youth have lived in limbo after the Trump Administration abruptly terminated DACA on September 5, 2017. After submitting personal information to DHS for deferred action, the threat of immigration enforcement has loomed over the once “safe” recipients of DACA, and anxieties have compounded during an increasingly deadly global pandemic. The decision to restore DACA as it was announced in 2012 saves the protection for now but resulted in venomous reactions from the Trump administration. Calls for Congressional action on immigration reform persist.