Offensive Speech • Unprotected Speech • Permissible Government Restrictions • Levels of Scrutiny • Political Speech

What are freedom of speech and expression?

The Constitution’s First Amendment gives individuals the right to express themselves. Freedom of speech is a basic form of expression, but the First Amendment covers much more than just speech.

An individual can express herself through religious practice; through political speech or actions; by associating with others; by petitioning the government; or by publicizing written speech. Even certain “speech actions” like flag burning are considered protected speech.

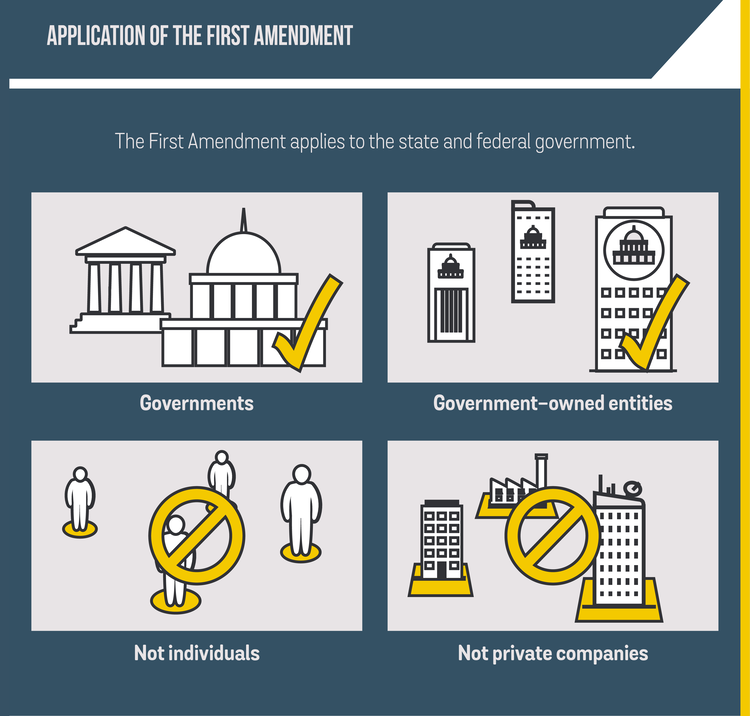

Free speech and expression are rights against the government. They are not rights against other people.

The government — whether federal, state or local — cannot prohibit an individual from expressing herself. That means all laws and policies must treat people equally based on their views. Government agents, from police officers to school board officials, must do so as well. Freedom of expression might also require the government to set an environment that enables individuals to speak, or to ensure that certain views are not inhibited from being expressed. The First Amendment may prevent President Trump from blocking certain views on Twitter, but it does not prevent non-government individuals from restricting their social media feeds based on viewpoint.

Offensive Speech May Still Be Protected Speech

The First Amendment prohibits the government from censoring speech or expression, even if many people would find the speech offensive. For example, flag burning is a form of protected speech. Likewise, speech for mere purposes of entertainment, vulgar speech, hate speech, and violent video games are all protected speech.

What Speech Is Not Protected?

The government is allowed to censor speech in certain circumstances. When the speaker has a certain relationship with the government, the government may restrict it. For example, the government can restrict speech by its employees if necessary to the employment role. For example, a public school teacher can be prohibited from promoting religious theory to students, and a national security employee can be prohibited from sharing confidential information.

In contrast, in Pickering v. Board of Education (1968), the Supreme Court ruled the government employer’s interest was not strong enough to overpower the free speech right of a public school teacher. The teacher had published a criticism of the school’s allocation of funds between educational and athletic programs. The Court ruled the teacher’s statements “were neither shown nor could be presumed to have interfered with [his] performance of his teaching duties or the schools’ general operation [and] were thus entitled to the same protection as if they had been made by a member of the general public.”

Categories of Unprotected Speech

Certain types of speech have “low” First Amendment value. This list from the National Constitution Center identifies several types of speech that have low or no First Amendment protection:

- Defamation: False statements that damage a person’s reputations can lead to civil liability (and even to criminal punishment), especially when the speaker deliberately lied or said things they knew were likely false. New York Times v. Sullivan (1964).

- b. True threats: Threats to commit a crime (for example, “I’ll kill you if you don’t give me your money”) can be punished. Watts v. United States (1969).

- “Fighting words”: Face-to-face personal insults that are likely to lead to an immediate fight are punishable. Chaplinsky v. New Hampshire (1942). But this does not include political statements that offend others and provoke them to violence. For example, civil rights or anti-abortion protesters cannot be silenced merely because passersby respond violently to their speech. Cox v. Louisiana (1965).

- Obscenity: Hard-core, highly sexually explicit pornography is not protected by the First Amendment. Miller v. California (1973). In practice, however, the government rarely prosecutes online distributors of such material.

- Child pornography: Photographs or videos involving actual children engaging in sexual conduct are punishable, because allowing such materials would create an incentive to sexually abuse children in order to produce such material. New York v. Ferber (1982).

- Commercial advertising: Speech advertising a product or service is constitutionally protected, but not as much as other speech. For instance, the government may ban misleading commercial advertising, but it generally can’t ban misleading political speech. Virginia Pharmacy v. Virginia Citizens Council (1976).

The Government Can Make Reasonable Content-Neutral Restrictions

The government cannot discriminate against someone based on her views. The government creates laws to maintain peace and order in the country, but the government cannot use its powers to enforce a particular view or to try to silence certain views. First Amendment challenges against laws have alleged that a law appears to apply equally to everyone but it tends to silence certain views.

The First Amendment says that the government may make reasonable speech restrictions, but the government may not favor or disfavor a certain idea over others.

For a speech restriction to be reasonable, the government must have a good interest for regulating or censoring speech. In 1939, the Supreme Court ruled a “law prohibiting all demonstrations in public parks or all leafleting on public streets” was unreasonable (National Constitution Center, citing Schneider v. State).

In 1992, the Supreme Court invalidated a criminal ordinance which prohibited the display of a symbol which “arouses anger, alarm or resentment in others on the basis of race, color, creed, religion or gender” (R.A.V. v. City of St. Paul). The Court said the government cannot prohibit speech based on the ideas expressed, and by restricting racist speech (and not positive speech), the ordinance violated the First Amendment.

Government regulations often require businesses to follow certain procedures or to provide certain notices in going about their business. Some cases have argued that business regulations require them to speak against their views in violation of the First Amendment. For example, in NIFLA v. Becerra (2018), pro-life women’s health clinics argued California regulations requiring them to provide certain notices about abortions violated their speech rights. The Supreme Court ruled the notices were likely in violation of the First Amendment because they regulated based on the content of the speech.

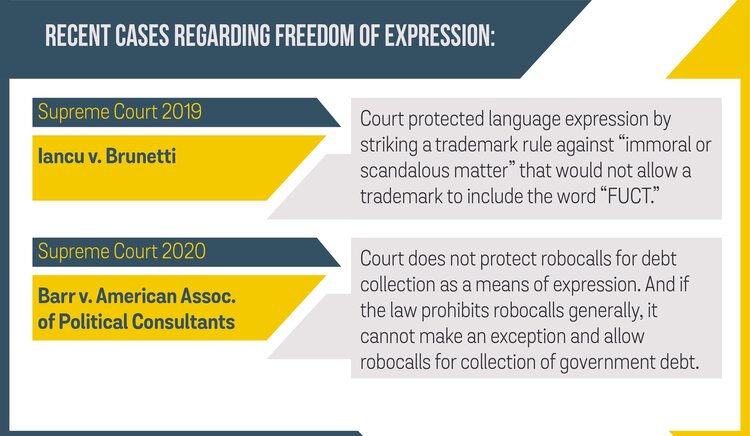

Recently the Supreme Court struck a rule of the Patent and Trademark Office that barred trademarks on “immoral or scandalous matter” (Iancu v. Brunetti, 2019). The Court also ruled against a content-based exception to a reasonable regulation against robocalls for purposes of debt collection. The government could not exclude calls for the collection of government debt from the general rule (Barr v. American Association of Political Consultants).

Levels of Scrutiny

When a court determines that a government law or policy restricts speech based on its content or viewpoint, the court will scrutinize the law to determine whether the purpose it serves is important enough to justify the speech restriction. The court will determine which level of scrutiny to apply based on the type of speech restriction, or the type of speech being restricted.

When it comes to a viewpoint-based speech restriction, the government must pass a high bar. A court will apply strict scrutiny. To pass strict scrutiny, the government must have a compelling interest to restrict the speech and the law must be “narrowly-tailored” to restrict the speech and only that speech. Similarly, if the government is restricting political speech, it must pass strict scrutiny because political speech deserves a high level of First amendment Protection.

Some types of speech get less First Amendment protection. Commercial speech — speech aimed to sell something — is one type of speech that is not as highly valued by the First Amendment. Thus restrictions on commercial speech usually get intermediate scrutiny when evaluated by courts. See this report from the Congressional Research Service for a listing of categories of speech and the treatment they get from courts.

Political Speech

Freedom of speech and expression are necessary to democracy because they encourage a diversity of views and debate.

A person should be able to promote her political views. Political speech is at the heart of the First Amendment because hearing and debating a diversity of views is necessary to a properly functioning democracy. The First Amendment prohibits the government from restricting political speech. This includes one’s right advocate politically, petition the government, rally others towards a cause, and especially one’s right to vote.

The First Amendment may also protect one’s right to spend money on a political cause. The value of money as speech — and whether the First Amendment protects it — has become a large and controversial topic. In 1976, the Supreme Court ruled that the government can impose limits on the amount of money an individual can contribute to a political campaign and a candidate because monetary limits protect our democracy against unscrupulous practices. However, in the same case, the Supreme Court ruled that various limits on expenditures in campaigns were invalid speech restrictions. Buckley v. Valeo (1976). In a controversial 2010 case, the Court ruled that corporations qualify for First Amendment protection and that they can spend unlimited money on political broadcasts in candidate elections. Citizens United v. FEC.

In Texas v. Johnson (1989), the Supreme Court determined that flag-burning is protected political speech and invalidated a Texas law outlawing flag desecration.

Recent Supreme Court Rulings, Political Speech

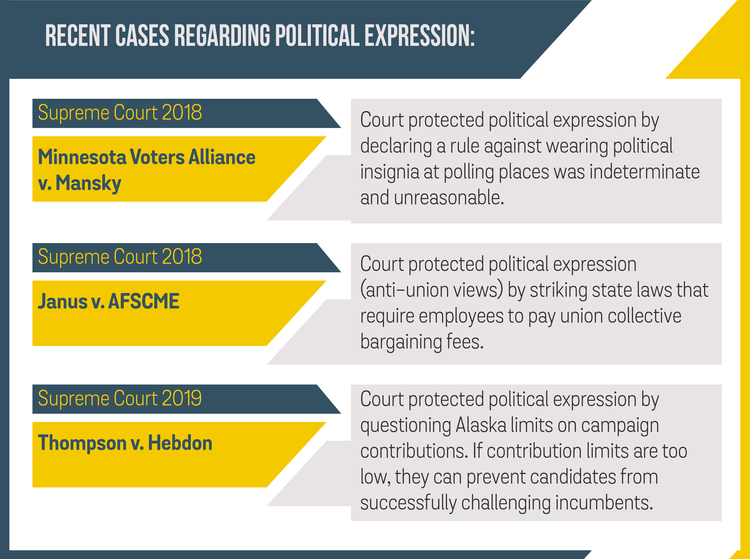

Recent Supreme Court cases on political speech demonstrate the diversity of issues coming under its banner. Janus v. AFSCME was the most controversial of recent cases. In Janus, the court addressed whether a state could require public employees to pay union collective bargaining fees. An Illinois employee argued that requiring him to support a union’s activities by paying the union required him to support a political idea in which he did not believe. Janus won in a 5-4 ruling with the support of the conservative wing. The case highlights how the First Amendment can prevent the government from providing what it determines is a public benefit (i.e. collective bargaining).

Minnesota Voters Alliance v. Mansky invalidated a rule prohibiting people from wearing political insignia at polling places. Thompson v. Hebdon remanded a case regarding the validity of an Alaska limit on campaign contributions, requiring the lower court to conduct a proper review of First Amendment concerns.

Rights of assembly, association and petition

The First Amendment also includes the rights to assemble, to associate with others, and to petition the government. These rights ensure that people have the opportunity to speak out and to rally others in support of their political views.

On October 5, 2020, the Supreme Court will hear Carney v. Adams, in which someone seeking a position on the Delaware judiciary claims a Delaware constitutional rule violates his right to freedom of association. The Delaware Constitution requires that positions on the state’s highest courts are split between the two major political parties. Adams, an independent, argues the law pressures him to associate with one of the two major political parties, or to give up his candidacy. Stay tuned for our reports on this case and other Supreme Court First Amendment issues.

More information:

For more information on free speech and free expression, see:

- National Constitution Center, Freedom of Speech and the Press, Interactive Constitution (last visited Aug. 17, 2020).

- Congressional Research Service, The First Amendment: Categories of Speech (Jan. 2019).

- ACLU, Free Speech (last visited Aug. 17, 2020).

- ACLU, Freedom of Expression (last visited Aug. 17, 2020).

- History.com, First Amendment (last updated Sept. 25, 2019).