Justices to make precedential ruling on proof required in age discrimination cases

In the United States Supreme Court

| Argument | January 15, 2020 |

| Decision | April 6, 2020 |

| Petitioner Brief | Noris Babb |

| Respondent Brief | Robert Wilkie, Secretary of Veterans Affairs |

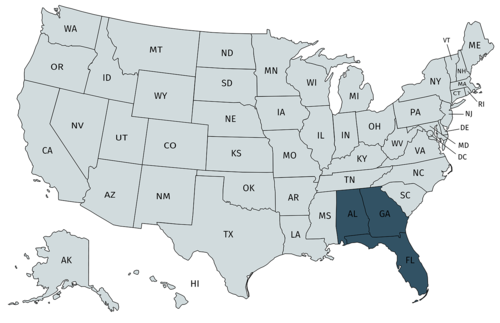

| Court Below |  Eleventh Circuit Court of Appeals |

Case Decision

The Supreme Court ruled in favor of Babb on April 6, 2020.

Scroll down for our Decision Analysis.

January 15, 2020

In 2014 Dr. Noris Babb, a clinical pharmacist, sued the Secretary of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), for employment discrimination. She filed under two different federal laws: the Age Discrimination in Employment Act of 1967 (ADEA) and the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (Title VII). Under the ADEA, she sued for age discrimination, and under Title VII she sued for discrimination based on her sex.

Babb’s lawsuit claimed that based on her age and sex, the VA: (1) limited her duties so as to hurt her chances of promotion; (2) denied her several promotions; (3) denied her training opportunities; and, when it later promoted her, (4) allocated her too little holiday pay. Babb also charged the VA with retaliating against her for supporting her colleagues’ charges of sex bias. Babb sought an injunction against what she described as ongoing age and sex bias against her, backpay and lost benefits related to the VA’s discrimination, as well as reimbursement for her attorneys’ fees and costs.

Issue in the Supreme Court

Babb’s case reaches the Supreme Court after a journey through the courts below. Her age discrimination claim suffered a defeat in the Eleventh Circuit Court of Appeals (just below the Supreme Court), while her sex discrimination claim stood to fight another day. The difference came down to the Eleventh Circuit’s interpretation of what it takes to prove an employer’s bias caused an adverse employment decision. Under Title VII, the Eleventh Circuit was satisfied with a lesser standard of proof, while under the ADEA, the Eleventh Circuit was bound by precedent requiring greater proof of causation.

Babb argues to the Supreme Court that the ADEA, like Title VII, supports a more lenient – standard of proving causation.

“But-for” versus “motivating factor” standards of causation

A litigant proves “but-for” causation by showing that an adverse decision would not have happened “but-for” an illegal bias. A lesser standard is called the “motivating factor” test. Under the motivating factor test, a litigant only needs to prove that the illegal bias (age or sex, for example) was one of the factors the defendant considered. She need not take the additional step to show the age or sex bias was determinative. It’s enough – and, thus, illegal, that the bias was considered.

In this case, Babb argues for a standard that is equivalent to the “motivating factor” standard. She argues it flows from the text of the ADEA.

Lower court decisions

After the parties conducted factual discovery, the trial court (the U.S. District Court for the Middle District of Florida) kicked out all of Babb’s claims. Although the court found that Babb had produced evidence of age and sex bias, the trial court determined that Babb had failed to show but-for causation on both the age and sex discrimination claims. Even if a reasonable jury could find that Babb had satisfied the motivating factor test, the court required “but-for” causation. Babb appealed.

The Eleventh Circuit Court of Appeals reversed only on Babb’s sex-discrimination claim. It ruled that Title VII (sex-discrimination) is satisfied with the motivating factor test, but the ADEA requires more stringent “but-for” causation. Babb argued that the relevant provisions of the ADEA and Title VII both expressly declare unlawful “any” age or sex discrimination in the process of federal agencies making personnel decisions like those that hurt Babb. In Babb’s view, the language means that the employer cannot consider age at all in making the personnel decisions at issue –the central feature of the motivating factor test.

The Court of Appeals concluded that its analysis of Babb’s ADEA claim was constrained by its own prior decisions. In particular, in 2016, the Court had applied a “but-for” causation standard to an ADEA discrimination claim by a federal employee. In contrast, the Court of Appeals noted that in another 2016 ruling, it had applied a more lenient “motivating factor” causation standard to a non-federal complainant under Title VII. The VA “d[id] not dispute” that the easier standard applied to Babb’s Title VII discrimination claim.

Based on Eleventh Circuit precedent, the Eleventh Circuit affirmed dismissal of Babb’s ADEA discrimination claim while reviving her Title VII discrimination claim (remanding it for reconsideration under the motivating factor standard). Significantly, the Court of Appeals observed that its 2016 decisions failed to account for significant differences in the language of the ADEA’s and Title VII’s private-sector and federal sector provisions. Were it “writing on a clean slate,” the Court said, if “might well agree” that a “motivating factor” causation standard – not a “but-for” standard should apply to Babb’s ADEA claims.

Arguments before the Supreme Court

Dr. Babb asks the U.S. Supreme Court to consider anew whether the broad wording of the federal-sector anti-discrimination provisions of the ADEA and Title VII warrant application of a more lenient causation standard — one like the “motivating factor” standard — instead of a stricter “but-for” causation standard. The Court agreed to consider this question in the context of the ADEA only, not under Title VII. Whether that division of labor is tenable, however, remains an open question.

In the Supreme Court, Babb makes what may be summarized as four arguments:

First, Babb has argued that the plain language of the ADEA, Section 633a(a) goes beyond banning discrimination that causes an unequal outcome based on age. That is, she contends, the Act is offended by mere use of the discriminatory factor (age). By using the language “shall be made free from any discrimination,” the ADEA did not intend to require a litigant to prove that such unequal treatment was a determinative factor in causing an unequal outcome. Thus, for instance, a rule requiring federal workers seeking promotion to pass a computer skills test if they are over age 40 should be illegal even if it cannot be shown that the results of such testing was a “but-for” cause of an older worker not being promoted. The process was tainted, Babb argues. And that is enough to satisfy Section 633a(a). Congress wanted federal workplaces to be “free from any discrimination,” the argument goes, not just results demonstrably due to ageist bias.

Babb also argues that the broad language in Section 633a(a) derives from similarly broad language in the federal sector provision of Title VII, which, in turn, derives from Congress’ desire to enact a “motivating factor” causation standard like that required by the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

Third, Babb contends that interpretations of the relevant statutes by federal administrative agencies support a motivating factor standard for Section 633a(a). Babb points to longstanding constructions of Section 2000e-16(a), on which Section 633a(a) is based, by the Civil Service Commission, as well as of Section 633a(a) itself, by the Equal Employment Opportunities Commission.

Finally, Babb asserts that the key cases relied by the Government – especially Gross v. FBL Fin. Servs. Inc., 557 U.S. 167 (2009) (ruling that a “but-for” causation standard applies to the ADEA’s private-sector discrimination prohibitions), and University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center v. Nassar, 570 U.S. 338 (2013) (finding that a “but-for” causation standard applies to Title VII’s ban on discriminatory retaliation in the private sector), do not govern interpretation of the ADEA’s federal-sector provision.

In response, the Government stresses several points. First, it notes that Sections 633a(a) and 2000e-16(a) contain the words “based on,” which courts in some contexts say means the same thing as the words “because of,” which, in turn, Gross and Nassar construed to require a “but-for” standard. The Government also maintains that the Supreme Court has made clear its allegiance to a “default rule” that statutes may be assumed to require proof of “but-for” causation absent clear evidence to the contrary – which the Governments says is lacking here.

Implications of a ruling in Babb

Despite the Supreme Court’s effort to avoid ruling on the causation standard in Title VII (in sex discrimination claims by federal employees), the Court’s decision in Babb is likely to point to (if not to provide) the standard in Title VII. A ruling for Babb might encourage a broad interpretation of the causation standard in both the ADEA (Section 633a(a)) and Title VII (Section 2000e-16(a)). A contrary ruling might have the opposite impact. And if the Court follows the government’s argument that statutes incorporate a “default rule” favoring “but-for” causation, the default is likely either to be read into many other statutes or to continue to be the subject of extensive litigation whose outcome will vary with specific circumstances presented by various statutory schemes.

DECISION ANALYSIS

Mariam Morshedi

On April 6, 2020, the Supreme Court ruled 8-1 in favor of the employee in Babb v. Wilkie. Noris Babb argued to the Court that the lower court used too strict of a standard in resolving her age discrimination claim.

Babb asked the Court to address the provision of the Age Discrimination in Employment Act requiring federal employers to make employment actions “free from” discrimination. She argued that language does not require the plaintiff to prove “but-for” causation. The Court majority agreed with Babb.

Justice Alito resolved the issue by interpreting the text of the Act. He wrote that “free from” discrimination means that an employment decision must not include any age discrimination at all. Even if the same decision might have been made without the consideration of age, the fact that age was considered makes the decision not “free from” discrimination. The government argued the Act requires a plaintiff to show the decision would not have been made “but-for” the age discrimination, but Alito rejected the argument because the text says otherwise.

Justice Thomas dissented, arguing that the ADEA’s federal sector provision should be interpreted to have the same standard as the many other discrimination statutes applying to the federal government. He says the majority should have required a “clear statement” (more clarification in the text of the law) to read a standard other than “but-for.”